I use sugar in Belgian beer to increase the ABV. If I added extra grain I couldn’t lift the grain basket. British beer does not need sugar, it was put in for economical reasons. I don’t brew bitters from 100 years ago I brew modern beers.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

English Ales - What's your favorite recipe?

- Thread starter Puddlethumper

- Start date

-

- Tags

- recipe

Help Support Homebrew Talk:

This site may earn a commission from merchant affiliate

links, including eBay, Amazon, and others.

But many modern brewers still use sugar, virtually all Timmy Taylor and Sam Smith ales use sugar, Harvey's are still fond of it, the list goes on.

By testiments of Ron P and others, even some breweries that pretend they don't use sugars have had blocks of Invert lieing around during tours etc. It was and still is an integral part to British brewing.

I personally find it gives British style ales a typical "lightness" and "lousciousness" that is nigh impossible to replicate without cane sugar.

By testiments of Ron P and others, even some breweries that pretend they don't use sugars have had blocks of Invert lieing around during tours etc. It was and still is an integral part to British brewing.

I personally find it gives British style ales a typical "lightness" and "lousciousness" that is nigh impossible to replicate without cane sugar.

Each to their own I make Landlord and Sussex without any sugar and they taste good.

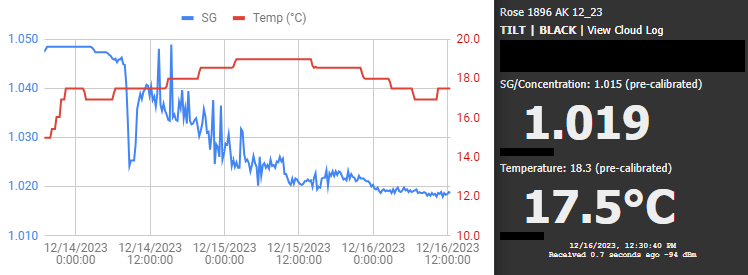

A commonly quoted reason for using sugar is to "thin" a potentially heavy beer. But as I've this (active) chart staring me in the face on this computer:

A "Rose" (from up north England) "1896 'AK' " (one of my favorities? Well, I've done it more then once). 9-10% sugars, yet that end gravity of 1.019 (it'll go down 2 or 3 points yet) can hardly be called "thin". The other big change (in only the last 10 years) is we have these "heritage" malts available to use now, "Chavallier", "Plumage Archer", even special edition "Maris Otter" (in use from 1975) that have been malted similar to methods used before 1980. And they finish at high gravities. As would be "normal" for earlier British beers.

Without the sugar this would have been finishing in the twenties (I was mashing slightly lower as well, at 65°C). The yeast helps too (for a higher gravity), this one being a low attenuative "Yorkshire" yeast: A particularily heavy cropping yeast which has been giving the (common style) "Tilt" hydrometer creating the above trace a very bumpy ride.

A "Rose" (from up north England) "1896 'AK' " (one of my favorities? Well, I've done it more then once). 9-10% sugars, yet that end gravity of 1.019 (it'll go down 2 or 3 points yet) can hardly be called "thin". The other big change (in only the last 10 years) is we have these "heritage" malts available to use now, "Chavallier", "Plumage Archer", even special edition "Maris Otter" (in use from 1975) that have been malted similar to methods used before 1980. And they finish at high gravities. As would be "normal" for earlier British beers.

Without the sugar this would have been finishing in the twenties (I was mashing slightly lower as well, at 65°C). The yeast helps too (for a higher gravity), this one being a low attenuative "Yorkshire" yeast: A particularily heavy cropping yeast which has been giving the (common style) "Tilt" hydrometer creating the above trace a very bumpy ride.

huckdavidson

Well-Known Member

A commonly quoted reason for using sugar is to "thin" a potentially heavy beer. But as I've this (active) chart staring me in the face on this computer:

View attachment 836668

A "Rose" (from up north England) "1896 'AK' " (one of my favorities? Well, I've done it more then once). 9-10% sugars, yet that end gravity of 1.019 (it'll go down 2 or 3 points yet) can hardly be called "thin". The other big change (in only the last 10 years) is we have these "heritage" malts available to use now, "Chavallier", "Plumage Archer", even special edition "Maris Otter" (in use from 1975) that have been malted similar to methods used before 1980. And they finish at high gravities. As would be "normal" for earlier British beers.

Without the sugar this would have been finishing in the twenties (I was mashing slightly lower as well, at 65°C). The yeast helps too (for a higher gravity), this one being a low attenuative "Yorkshire" yeast: A particularily heavy cropping yeast which has been giving the (common style) "Tilt" hydrometer creating the above trace a very bumpy ride.

Would the yeast poop out resulting in an even higher FG if the sugar weren't inverted first or does it even matter? Might depend on yeast strain... (not suggesting that you have or have not used invert)

You don't think they would stop using sugar if they knew what you do?Each to their own I make Landlord and Sussex without any sugar and they taste good.

Sugar is used for many reasons and I brew most beers with sugar for more reasons than authenticity. I've learned a lot from trying different methods of brewing and in other disciplines.

For a lot of years, most breweries in Britain were designed to brew with sugar as a major ingredient.

$58.16

HUIZHUGS Brewing Equipment Keg Ball Lock Faucet 30cm Reinforced Silicone Hose Secondary Fermentation Homebrew Kegging Brewing Equipment

xiangshuizhenzhanglingfengshop

![Craft A Brew - Safale S-04 Dry Yeast - Fermentis - English Ale Dry Yeast - For English and American Ales and Hard Apple Ciders - Ingredients for Home Brewing - Beer Making Supplies - [1 Pack]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/41fVGNh6JfL._SL500_.jpg)

$6.95 ($17.38 / Ounce)

$7.47 ($18.68 / Ounce)

Craft A Brew - Safale S-04 Dry Yeast - Fermentis - English Ale Dry Yeast - For English and American Ales and Hard Apple Ciders - Ingredients for Home Brewing - Beer Making Supplies - [1 Pack]

BellaRae

$22.00 ($623.23 / Ounce)

AMZLMPKNTW Ball Lock Sample Faucet 30cm Reinforced Silicone Hose Secondary Fermentation Homebrew Kegging joyful

无为中南商贸有限公司

$53.24

1pc Hose Barb/MFL 1.5" Tri Clamp to Ball Lock Post Liquid Gas Homebrew Kegging Fermentation Parts Brewer Hardware SUS304(Gas MFL)

yunchengshiyanhuqucuichendianzishangwuyouxiangongsi

$176.97

1pc Commercial Keg Manifold 2" Tri Clamp,Ball Lock Tapping Head,Pressure Gauge/Adjustable PRV for Kegging,Fermentation Control

hanhanbaihuoxiaoshoudian

$53.24

1pc Hose Barb/MFL 1.5" Tri Clamp to Ball Lock Post Liquid Gas Homebrew Kegging Fermentation Parts Brewer Hardware SUS304(Gas Hose Barb)

Guangshui Weilu You Trading Co., Ltd

$45.74 ($45.74 / Count)

Brewer's Best Home Brew Beer Ingredient Kit - 5 Gallon (Grapefruit IPA)

Amazon.com

$7.79 ($7.79 / Count)

Craft A Brew - LalBrew Voss™ - Kveik Ale Yeast - For Craft Lagers - Ingredients for Home Brewing - Beer Making Supplies - (1 Pack)

Craft a Brew

$33.99 ($17.00 / Count)

$41.99 ($21.00 / Count)

2 Pack 1 Gallon Large Fermentation Jars with 3 Airlocks and 2 SCREW Lids(100% Airtight Heavy Duty Lid w Silicone) - Wide Mouth Glass Jars w Scale Mark - Pickle Jars for Sauerkraut, Sourdough Starter

Qianfenie Direct

$82.50

Wilbur Curtis Brew Cone Assembly with Splash Pocket, High Volume - Commercial-Grade Brew Basket - WC-3422 (Each)

Global Commercial Parts

$10.99 ($31.16 / Ounce)

Hornindal Kveik Yeast for Homebrewing - Mead, Cider, Wine, Beer - 10g Packet - Saccharomyces Cerevisiae - Sold by Shadowhive.com

Shadowhive

Nay! The yeast is perfectly capable of dealing with sucrose. @DuncB posted something on yeast being used to "invert" sugar (English Ales - What's your favorite recipe?). But glucose is supposed to have some influence on "esters" - not that I can tell - but that Rose AK recipe calls for "white sugar" (unusual ingredient for 19th C.) so I replaced it with corn sugar (which they certainly did use in brewing later in the 19th C.). The replacement was purely a whim of mine ... no evidence for it.Would the yeast poop out resulting in an even higher FG if the sugar weren't inverted first or does it even matter? Might depend on yeast strain... (not suggesting that you have or have not used invert)

If I remember rightly, the yeast releases "invertase" externally to deal with sucrose, and so sucrose is consumed before the maltose in the wort. The yeast splits maltose internally (into glucose).

The other sugar in the Rose AK recipe is "Brewers' Invert Sugar No.2" for which I did use one of my (infamous?) emulations (no inversion and no caramelisation). But I'm not to talk of that or I may start a bun fight!

huckdavidson

Well-Known Member

Nay! The yeast is perfectly capable of dealing with sucrose. @DuncB posted something on yeast being used to "invert" sugar (English Ales - What's your favorite recipe?). But glucose is supposed to have some influence on "esters" - not that I can tell - but that Rose AK recipe calls for "white sugar" (unusual ingredient for 19th C.) so I replaced it with corn sugar (which they certainly did use in brewing later in the 19th C.). The replacement was purely a whim of mine ... no evidence for it.

If I remember rightly, the yeast releases "invertase" externally to deal with sucrose, and so sucrose is consumed before the maltose in the wort. The yeast splits maltose internally (into glucose).

The other sugar in the Rose AK recipe is "Brewers' Invert Sugar No.2" for which I did use one of my (infamous?) emulations (no inversion and no caramelisation). But I'm not to talk of that or I may start a bun fight!

That's interesting, so inverting the sucrose doesn't stress the yeast affecting the further processing of the remaining sucrose and maltose in the wort? Just out of curiosity then what is the mechanism by which a yeast stops processing sugars? Why do some yeast finish at a higher gravity than others?

Malt is a polysaccharide. Made of many sugars joined together. Some yeasts have enzymes that can chop that polysaccharide up into fully metabolisable pieces, ie a saison yeast.Why do some yeast finish at a higher gravity than others?

Others such as Windsor can't do this as can't break maltotriose bond ( I think).

Some yeasts can only metabolise glucose such as metschinkowa reukaufii. Less metabolism means more sugar taste and body.

Yeasts also stop at certain alcohol levels so seen with very high gravity ales.

I've seen one suggestion that it may disadvantage yeast cropping down the generations? But I don't repeatedly repitch my yeast anyway. I reckon "inverting" was a handy way to break into the sugar refining chain and have a product in handy syrup form rather than a crystalising mess. More "reasons" for inverting was invented at a later date ("hind-sight").That's interesting, so inverting the sucrose doesn't stress the yeast affecting the further processing of the remaining sucrose and maltose in the wort? Just out of curiosity then what is the mechanism by which a yeast stops processing sugars? Why do some yeast finish at a higher gravity than others?

Modern refining doesn't fit into the myths so well, so the majority of breweries switched to sucrose syrups in the 1960s (in Britian that is). See also:

http://edsbeer.blogspot.com/2016/05/the-rise-and-fall-of-invert-sugar.html

As for "Final Gravity":

(Much the same as @DuncB said...):

Yeast can ferment "trisaccharide" (like malt-triose) but some yeasts better than others. I generally look for attenuation rates of about 68-70% to suggest the yeast is incapable of digesting malt-triose, through to 80% suggesting it has no bother. Some yeasts can breakdown longer chain saccharide (var. diastaticus or sta-1 positive strains) and these may have figures higher then 80%.

That "malt-triose" stuff is all conjecture, but it suits me well enough. There's no hard-and-fast boundaries in reality.

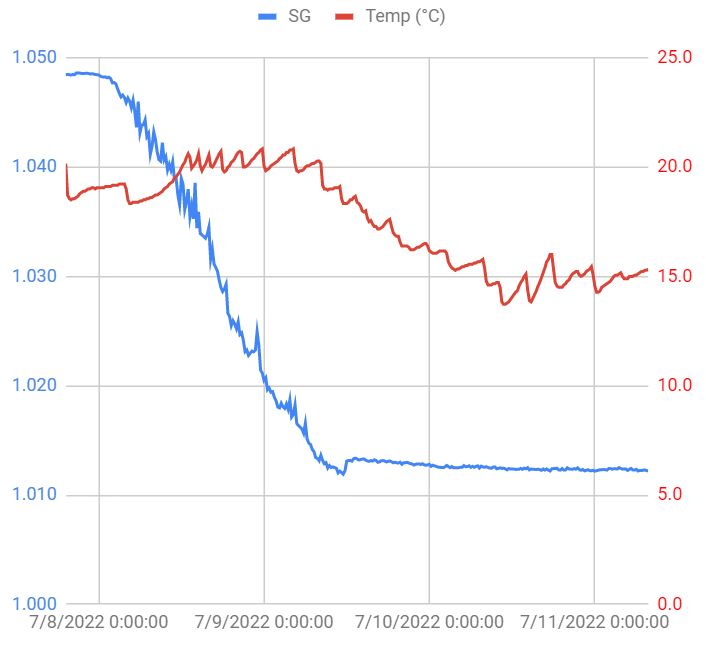

Here's an example; the yeast hits FG like a ton of bricks:

There was a lot of sugar in that recipe, hence the FG still got fairly low. Note FG in less than 36 hours.

Good for you I don’t use sugar in my British beers your choice my choice.You don't think they would stop using sugar if they knew what you do?

Sugar is used for many reasons and I brew most beers with sugar for more reasons than authenticity. I've learned a lot from trying different methods of brewing and in other disciplines.

For a lot of years, most breweries in Britain were designed to brew with sugar as a major ingredient.

McMullan

wort maker

- Joined

- Dec 22, 2015

- Messages

- 2,566

- Reaction score

- 3,461

Brewing is about one thing, fundamentally; producing alcohol. That's what brewers do. They produce alcoholic beverages. Beer. Adding sugar boosts alcohol production with minimal effort in the brewery. Although once a highly valued commodity, when first imported to Europe from Asia, and far too expensive to use in brewing, cane sugar production increased (prices went down) due to slavery. Then supplies further increased (prices got even cheaper) for Britain exclusively, in Europe, because the British navy blockaded supplies to the rest of Europe during the Napoleonic wars. "Ahoy, what shall we do with all this surplus sweet stuff, you bilge-sucking scallywags?" So supplies increased dramatically for British brewers and others. "Sink me, you scurvy dogs!" It worked surprisingly well. It boosted the alcohol content and added a luscious character that complemented English ales at the time. That's all it was, primarily. No need to complicate life. Just a fortuitous discovery by chance events really.

At some point, using invert (monosaccharide) additions became the thing to do. Actually for quite obvious reasons as it transpired back then, not just today. It's documented in the literature from the 19th and early 20th century. It's not just a 'cheat' attenuation booster, to produce more ethanol, it's a fermentation (yeast) aid. Adding 10-30% fermentables as sucrose (a disaccharide), on top of the approximately 5% from grain, adds a significant biological burden (stress) on yeast cells, and risks a classic home brew 'twang'. They actually need to do some work (biochemistry) to process it. They can't break the laws of physics. Do the biology, trying not to assume - like so many brewers do - that yeast cells are just tiny little particles converting sugar to ethanol and CO2. It's a little bit more complicated than that. Biology, that is. Anyway, invert (monosaccahride) is much easier to process therefore requires much less work by the yeast cells. Not that anyone needs to know about it. You don't. But the fact is, British brewers in the 19th clearly realised, quite fortuitously, that adding cane invert to brewery worts was beneficial in terms of increasing attenuation and adding subtle flavour characteristics reflecting elements of already established tastes based on widely used cane sugar. It was documented in their publications.

If we use refined sugar (sucrose, from cane, beet or whatever - it's all the same thing, sucrose), it imparts practically zero flavour. It's essentially pure sucrose. If we use invert from refined sugar, again, it imparts practically zero flavour. But you'll get a better fermentation, a beer that conditions sooner and yeast that are better for repitching. Think about it, from the perspective of a brewer. It's why so many breweries, including big macros, use monosaccharide additions in one form or another today. It's standard practice in many breweries. Purist all-grain home brewers have simply been in denial about the benefits of sugar additions. Ironic really, because all all-grain fermentable sugars in wort end up as a form of the monosaccharide glucose. More biology.

So where does the 'legendary' luscious character come from? Cane molasses, of course. Added by using unrefined cane sugar in the first place and/or adding cane molasses to invert made from refined or unrefined sucrose. More molasses produces more flavour. Taste some. It's not rocket science. It's what the last remaining UK-based manufacturer of British brewing inverts does, which has been detailed sufficiently already and interpreted to varying degrees of accuracy by a number of home brewers for years. There's nothing new to see here. It's all old hat.

Summary: Inverted sucrose (cane, beet or whatever, in reality) boosts attenuation (alcohol production), helps promote a better fermentation, a beer that conditions sooner and yeast that are better for repitching. Adding cane molasses adds a lusciousness that complements the subtle complexities of traditional English ales.

It's only beer. It's not supposed to be complicated. Why some need to complicate the world only they know.

At some point, using invert (monosaccharide) additions became the thing to do. Actually for quite obvious reasons as it transpired back then, not just today. It's documented in the literature from the 19th and early 20th century. It's not just a 'cheat' attenuation booster, to produce more ethanol, it's a fermentation (yeast) aid. Adding 10-30% fermentables as sucrose (a disaccharide), on top of the approximately 5% from grain, adds a significant biological burden (stress) on yeast cells, and risks a classic home brew 'twang'. They actually need to do some work (biochemistry) to process it. They can't break the laws of physics. Do the biology, trying not to assume - like so many brewers do - that yeast cells are just tiny little particles converting sugar to ethanol and CO2. It's a little bit more complicated than that. Biology, that is. Anyway, invert (monosaccahride) is much easier to process therefore requires much less work by the yeast cells. Not that anyone needs to know about it. You don't. But the fact is, British brewers in the 19th clearly realised, quite fortuitously, that adding cane invert to brewery worts was beneficial in terms of increasing attenuation and adding subtle flavour characteristics reflecting elements of already established tastes based on widely used cane sugar. It was documented in their publications.

If we use refined sugar (sucrose, from cane, beet or whatever - it's all the same thing, sucrose), it imparts practically zero flavour. It's essentially pure sucrose. If we use invert from refined sugar, again, it imparts practically zero flavour. But you'll get a better fermentation, a beer that conditions sooner and yeast that are better for repitching. Think about it, from the perspective of a brewer. It's why so many breweries, including big macros, use monosaccharide additions in one form or another today. It's standard practice in many breweries. Purist all-grain home brewers have simply been in denial about the benefits of sugar additions. Ironic really, because all all-grain fermentable sugars in wort end up as a form of the monosaccharide glucose. More biology.

So where does the 'legendary' luscious character come from? Cane molasses, of course. Added by using unrefined cane sugar in the first place and/or adding cane molasses to invert made from refined or unrefined sucrose. More molasses produces more flavour. Taste some. It's not rocket science. It's what the last remaining UK-based manufacturer of British brewing inverts does, which has been detailed sufficiently already and interpreted to varying degrees of accuracy by a number of home brewers for years. There's nothing new to see here. It's all old hat.

Summary: Inverted sucrose (cane, beet or whatever, in reality) boosts attenuation (alcohol production), helps promote a better fermentation, a beer that conditions sooner and yeast that are better for repitching. Adding cane molasses adds a lusciousness that complements the subtle complexities of traditional English ales.

It's only beer. It's not supposed to be complicated. Why some need to complicate the world only they know.

McMullan

wort maker

- Joined

- Dec 22, 2015

- Messages

- 2,566

- Reaction score

- 3,461

So you make alcohol free beer?Good for you I don’t use sugar in my British beers your choice my choice.

He's back!Brewing is about one thing, fundamentally; producing alcohol. That's what brewers do. They produce alcoholic beverages. Beer. Adding sugar boosts alcohol production with minimal effort in the brewery. Although once a highly valued commodity, when first imported to Europe from Asia, and far too expensive to use in brewing, cane sugar production increased (prices went down) due to slavery. Then supplies further increased (prices got even cheaper) for Britain exclusively, in Europe, because the British navy blockaded supplies to the rest of Europe during the Napoleonic wars. "Ahoy, what shall we do with all this surplus sweet stuff, you bilge-sucking scallywags?" So supplies increased dramatically for British brewers and others. "Sink me, you scurvy dogs!" It worked surprisingly well. It boosted the alcohol content and added a luscious character that complemented English ales at the time. That's all it was, primarily. No need to complicate life. Just a fortuitous discovery by chance events really.

At some point, using invert (monosaccharide) additions became the thing to do. Actually for quite obvious reasons as it transpired back then, not just today. It's documented in the literature from the 19th and early 20th century. It's not just a 'cheat' attenuation booster, to produce more ethanol, it's a fermentation (yeast) aid. Adding 10-30% fermentables as sucrose (a disaccharide), on top of the approximately 5% from grain, adds a significant biological burden (stress) on yeast cells, and risks a classic home brew 'twang'. They actually need to do some work (biochemistry) to process it. They can't break the laws of physics. Do the biology, trying not to assume - like so many brewers do - that yeast cells are just tiny little particles converting sugar to ethanol and CO2. It's a little bit more complicated than that. Biology, that is. Anyway, invert (monosaccahride) is much easier to process therefore requires much less work by the yeast cells. Not that anyone needs to know about it. You don't. But the fact is, British brewers in the 19th clearly realised, quite fortuitously, that adding cane invert to brewery worts was beneficial in terms of increasing attenuation and adding subtle flavour characteristics reflecting elements of already established tastes based on widely used cane sugar. It was documented in their publications.

If we use refined sugar (sucrose, from cane, beet or whatever - it's all the same thing, sucrose), it imparts practically zero flavour. It's essentially pure sucrose. If we use invert from refined sugar, again, it imparts practically zero flavour. But you'll get a better fermentation, a beer that conditions sooner and yeast that are better for repitching. Think about it, from the perspective of a brewer. It's why so many breweries, including big macros, use monosaccharide additions in one form or another today. It's standard practice in many breweries. Purist all-grain home brewers have simply been in denial about the benefits of sugar additions. Ironic really, because all all-grain fermentable sugars in wort end up as a form of the monosaccharide glucose. More biology.

So where does the 'legendary' luscious character come from? Cane molasses, of course. Added by using unrefined cane sugar in the first place and/or adding cane molasses to invert made from refined or unrefined sucrose. More molasses produces more flavour. Taste some. It's not rocket science. It's what the last remaining UK-based manufacturer of British brewing inverts does, which has been detailed sufficiently already and interpreted to varying degrees of accuracy by a number of home brewers for years. There's nothing new to see here. It's all old hat.

Summary: Inverted sucrose (cane, beet or whatever, in reality) boosts attenuation (alcohol production), helps promote a better fermentation, a beer that conditions sooner and yeast that are better for repitching. Adding cane molasses adds a lusciousness that complements the subtle complexities of traditional English ales.

It's only beer. It's not supposed to be complicated. Why some need to complicate the world only they know.

Hopefully not with a vengeance

McMullan

wort maker

- Joined

- Dec 22, 2015

- Messages

- 2,566

- Reaction score

- 3,461

I'm not sure about the procedures used when baking (or simmering) for extended times, to be honest. You'd have already inverted the coconut sucrose before baking. I'd have just added some cane molasses instead of heating for an hour or two or more. Something I had in my mind, but forget to add above, molasses are very nutritious, which is why yeast are cultured on the stuff commercially. Just adding invert (or sucrose) is like adding empty calories for the yeast. Another good reason to add molasses rather than heat for ages, in my mind.Welcome back @McMullan I missed your help.

Just inverting some coconut sugar.

Do I neutralise the acid before the long oven stage. I've simmered with citric for an hour.

Welcome back @McMullan I missed your help.

Just inverting some coconut sugar.

Do I neutralise the acid before the long oven stage. I've simmered with citric for an hour.

If the citric acid addition lowers pH to circa 2.2, a 15 minutes gentle simmer can invert most sucrose. Further heating from that point can serve to first destroy the fructose, which has a melting point of 103C. The influence of further baking depends upon the water to sugar ratio, for the lower that ratio, the higher the boiling point of the solution.

I invert with a ratio of water:sucrose (granulated white refined cane sugar) of 1:2. The water is first titrated with HCl to pH 4.4 to eliminate all alkalinity. This mixture will be close to saturation at 70C, hazy white and not perfectly translucent. At that temperature, more acid is added to reduce pH to between pH 2.2 and 2, with heat applied together with stirring. The mixture begins to clear as the sucrose starts inverting to more soluble glucose and fructose. After several minutes, typically fifteen, the mixture begins to take on a slight straw colour and I take this to be the end point of inversion of the sucrose. Then I will add darker sugars if a darker invert is desired, which will ordinarily slow the conversion, particularly if the added content has a proportion of sucrose, such as molasses. after a few minutes the process is stopped by placing the pan into cold water in the kitchen sink, and the job completed with a gram or two of sodium bicarbonate.

I play your Yorkshire square fermenting on a continuous loop on the television.@McMullan

We are in desperate need of some more home made yorkshire square-porn!

No finer programming available.

I wouldn't have dared tread back in time as far as @McMullen: Napoleonic Wars* well predates even "Brewers' Invert Sugars". The sugars brewers would often use would be the dregs in the bottom of the barrels ... The extra messy stuff full of "molasses" that had drained off (but not entirely!) the crystallised sucrose during shipment. Most of the "molasses" had been tapped off before shipment; the sugar barrels having been stashed aside for a few weeks to let most of the molasses drain (assuming it was from the W. Indies we're talking about). They wanted the molasses for making rum!

Interestingly, shortly after the Napoleonic Wars, the UK government made sugar in beer (along with assorted other junk and poisons) illegal. Sugar wasn't allowed back in until 1847 (some earlier brief exceptions to allow for bad grain harvests), and wasn't used much in beer until after 1870/80 (from reading too much stuff by Ron Pattinson instead of doing something useful ... according to my partner). Obviously the "freedom" to add what they liked to beer, including cheap sugar, during the Napolean times was an excuse to add any old (sometimes toxic) junk to beer, and the abuse had to stop?

BTW: Molasses isn't a specific thing, it's the "mother liquor", a mix of "stuff" from which the sucrose is crystallised. It still contains a lot of sucrose, perhaps 60%, along with glucose and fructose (like in Invert Sugar, which is helping keep it liquid) and assorted cr&p including caramelised (burnt!) sugar and even the ever-popular Maillard Reaction products (they weren't going to be explained for over a century, but that doesn't mean they weren't there). Lime was used during the early stages of sugar extraction which incidentally helped create the alkaline environment favored by Maillard Reactions (mention of Maillard reaction products makes me cringe, but I know their presence is popular in brewing discussions at the moment).

That's really getting to the limits of my current sugar knowledge; hence I started this post with "further back than I (should of) dare tread".

*For the telly watchers: That's the time the BBC series "Sharpe" (Sean Bean) and his soldiering antics in Spain/Portugal is set.

Interestingly, shortly after the Napoleonic Wars, the UK government made sugar in beer (along with assorted other junk and poisons) illegal. Sugar wasn't allowed back in until 1847 (some earlier brief exceptions to allow for bad grain harvests), and wasn't used much in beer until after 1870/80 (from reading too much stuff by Ron Pattinson instead of doing something useful ... according to my partner). Obviously the "freedom" to add what they liked to beer, including cheap sugar, during the Napolean times was an excuse to add any old (sometimes toxic) junk to beer, and the abuse had to stop?

BTW: Molasses isn't a specific thing, it's the "mother liquor", a mix of "stuff" from which the sucrose is crystallised. It still contains a lot of sucrose, perhaps 60%, along with glucose and fructose (like in Invert Sugar, which is helping keep it liquid) and assorted cr&p including caramelised (burnt!) sugar and even the ever-popular Maillard Reaction products (they weren't going to be explained for over a century, but that doesn't mean they weren't there). Lime was used during the early stages of sugar extraction which incidentally helped create the alkaline environment favored by Maillard Reactions (mention of Maillard reaction products makes me cringe, but I know their presence is popular in brewing discussions at the moment).

That's really getting to the limits of my current sugar knowledge; hence I started this post with "further back than I (should of) dare tread".

*For the telly watchers: That's the time the BBC series "Sharpe" (Sean Bean) and his soldiering antics in Spain/Portugal is set.

McMullan

wort maker

- Joined

- Dec 22, 2015

- Messages

- 2,566

- Reaction score

- 3,461

Yes. And? Don't fortuitous practices ever have beginnings that develop? The point was, cane sugar clearly became a viable (affordable) option in surplus for early 19th century brewers, due to blockades enforced by the British navy during the Napoleonic wars, which was why the French invested in sugar beet. Whatever draconian British legislation followed, after whatever events caused by poor practices (taxation or chemistry, or the abuse of one to favour the other), didn't really prevent what clearly became standard practice of cane sugar additions to English ales, it looks like. At least in my uncomplicated world.Napoleonic Wars* well predates even "Brewers' Invert Sugars".

Last edited:

@Peebee: To further your historical analysis and muck things up even more..... they probably used the old way of using slaked lime water for the acidic to cause inversion, then probably gypsum to neutralize it. of course the added ppm of each would affect the water composition.

So the old Dave Line's "glucose chips" were probably born from the "old way" of this in general.

Rather than leaving it up to chance of the affect on the water, if I could figure out the ppm contribution of the above said "glucose chips" on a per pound basis, I could deduct from my water additions and have control. Then it would be cool to re-create these chips, being it would actually have a two part purpose: Taste of inverted sugar, and water contribution that is controlled.

Edit: I might want to add that acid has been shown to emulsify gypsum, actually allowing it to be incorporated into water.

So the old Dave Line's "glucose chips" were probably born from the "old way" of this in general.

Rather than leaving it up to chance of the affect on the water, if I could figure out the ppm contribution of the above said "glucose chips" on a per pound basis, I could deduct from my water additions and have control. Then it would be cool to re-create these chips, being it would actually have a two part purpose: Taste of inverted sugar, and water contribution that is controlled.

Edit: I might want to add that acid has been shown to emulsify gypsum, actually allowing it to be incorporated into water.

Last edited:

huckdavidson

Well-Known Member

@Peebee: To further your historical analysis and muck things up even more..... they probably used the old way of using slaked lime water for the acidic to cause inversion, then probably gypsum to neutralize it. of course the added ppm of each would affect the water composition.

So the old Dave Line's "glucose chips" were probably born from the "old way" of this in general.

Rather than leaving it up to chance of the affect on the water, if I could figure out the ppm contribution of the above said "glucose chips" on a per pound basis, I could deduct from my water additions and have control. Then it would be cool to re-create these chips, being it would actually have a two part purpose: Taste of inverted sugar, and water contribution that is controlled.

Edit: I might want to add that acid has been shown to emulsify gypsum, actually allowing it to be incorporated into water.

Slaked lime is an alkali used to raise pH, how would it be used to lower pH - or are you saying inversion also occurs at a high pH?

How would gypsum be used to neutralize an alkaline water?

I haven't seen glucose chips in over two decades give or take.

InspectorJon

Well-Known Member

Maybe he has those backwards. I know that when I add gypsum using a water calculator it lowers mash pH and pickling lime raises pH. When he first said lime I thought of the fruit, West Indies and all. That would lower pH. People have mentioned using lemon juice to make inverted sugar.Slaked lime is an alkali used to raise pH, how would it be used to lower pH - or are you saying inversion also occurs at a high pH?

huckdavidson

Well-Known Member

Maybe he has those backwards. I know that when I add gypsum using a water calculator it lowers mash pH and pickling lime raises pH. When he first said lime I thought of the fruit, West Indies and all. That would lower pH. People have mentioned using lemon juice to make inverted sugar.

The interaction of calcium with mash components such as phosphates is what lowers mash pH. The interaction of adding gypsum to a slaked lime solution does nothing of the sort. Lime and lemon juices are acidic and may act to lower the pH of a solution.

https://braukaiser.com/blog/blog/2011/02/01/calcium-and-magnesiums-effect-on-mash-ph/

Last edited:

huckdavidson

Well-Known Member

Lime is used in the industrial beet sugar making process to "capture and remove impurities in the juice of sugar beet" and "it is also often used to clean and neutralise wastewater produced by sugar beet". The byproducts of those processes are also useful. None of that has anything to do with the inversion process.

Wrong! Lime was for clarifying the juice. Other useful effects were incidental (though they probably understood by then that lime prevented "inversion"). They certainly didn't want it "inverting" at-all ... they would not get any sugar out that way, the syrup would remain liquid (no crystallisation). Check out "strike" in early refining, a particularly skillful procedure that if done wrong resulted in a useless sludge of molasses.they probably used the old way of using slaked lime water for the acidic to cause inversion ...

Oops, sorry, you'd already figured the lime was for purifying/clarifying ... and they still use it in modern refining!

I don't think they use another component with lime these days (egg whites or blood!).

[EDIT: Being a Brit I only said Lime 'cos I couldn't remember how it was referred to over there: Pickling Lime; I know now, although I think everyone would understand if I'd said Slaked Lime.]

Last edited:

Similar threads

- Replies

- 7

- Views

- 3K

- Replies

- 18

- Views

- 2K

- Replies

- 27

- Views

- 6K