Charlie ColoHox Hoxmeier

New Member

- Joined

- May 7, 2015

- Messages

- 3

- Reaction score

- 0

Link back to Science on Tap part 1: Introduction to the science of beer aging.

We have all heard the rules for selecting a beer for aging: high ABV and low hops, dark-colored, imperial, etc. Really though, you can choose to age any beer. But why do some beers deteriorate deliciously while others degenerate disastrously? While the focus here is primarily post-fermentation, we can start with the components of particular styles that allow for better aging performance.

The storage conditions influence the speed and extent of the aging reactions that occur in beer, as mentioned before (Part 1). However, the concentration of the precursor chemicals involved in these reactions will also influence their progression. These precursors come from our choice of ingredients, and process variables (oxygenation, temperature, etc). Regardless of the particular style, a brewer must use well-practiced techniques with regard to sanitation, and choose fresh, high-quality ingredients. The best practice is to avoid generating off-flavor associated compounds from the start by removing chlorine/chloramine from your water, managing fermentation temperature, and avoiding oxygen and microbes. Rarely, does an off-flavor discovered in a fresh beer "age out" over time. However, this "aging out" can happen in certain instances, which I will discuss later.

Change in sensory perception of lager over time. Note transition from estery and bitter to sweet and papery over time. (Wu et. al. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2011, 12(9), 6089-6103)

Why do darkly colored beers age better than lightly colored beers? Generally, this has to do with the robustness and composition of the flavors. Darker beers are made from dark, roasted malts. These malts provide many flavorful volatile compounds. When brewing with these malts, we depend on a particular reaction to develop the sought after flavors: the Maillard reaction. The Maillard reaction is a non-enzymatic combination between an amino acid (from protein) and sugar (from mashing). Maillard reactions occur during malting and the boil, producing a huge diversity of products that contribute to flavor, and in particular, melanoidins.

Melanoidins form through a wide variety of chemical rearrangement and recombination of the Maillard products, resulting in darkly colored nitrogen based compounds that provide an intense malty character (some are also antioxidants and antimicrobials!). During aging, small products of the Maillard reaction can polymerize to form larger compounds with new flavors. In beers with a high percentage of dark malts, a higher proportion of particular flavor active compounds (carbonyls, Strecker aldehydes, furfural alcohols, and Maillard reaction intermediates), provide significant antioxidant capability. Together, many of these compounds are associated with staling in light colored beers, but in darkly colored beers, they provide a sweet and malty impression and enhance long-term flavor stability. The aging process of dark beers is characterized by the development of burnt, alcoholic, caramel, liquorice and astringent flavors. These strong flavors mask the evolution of stale flavors that is occurring concurrently. A word of caution though: The (often) higher acidity from roasted malts is hard on the yeast remaining in the beer during aging. This can result is meaty/soy sauce flavors as the yeast dies.

Why shouldn't I age hoppy beers? You can, of course. But why would you? Even in the time it takes to finish a keg or case of bottles of your house IPA, most people can appreciate that the hop aroma (in particular) fades very quickly. The flavor eventually goes too. Moreover, a beer that is not highly hopped will be less likely to develop stale off-flavors. Bitter acids from hops (the iso-alpha, alpha, and beta acids) are quickly broken down, mostly due to oxidative processes. This degradation results in a decrease in bitterness (recall the Dalgliesh chart from part 1), but also in the formation of new compounds. These new compounds include a variety of carbonyls like (E)2-nonenal (stale), acetone (solventy), butanol and propanol (alcoholic/solventy), and butyric and propionic acid (cheesey/sulfur/sweaty). Again, I need to point out, that while these processes are likely occurring in an aged, hop-forward beer, it does not mean that these flavors are always detectable, nor considered off-flavors when the total flavor profile of the beer is considered. Regardless of the changes or flavors, you lose more than you gain when you age hoppy beers due to the abundance of precursor chemicals potentially resulting in off-flavors after degradation. A way to avoid some of these changes is to use hops with a high proportion of beta-acids (Lupulone, Colupulone, Adlupulone) like Amarillo or Galena. The beta-acids tend to maintain their bitterness over time and can age into fruity flavors as they degrade.

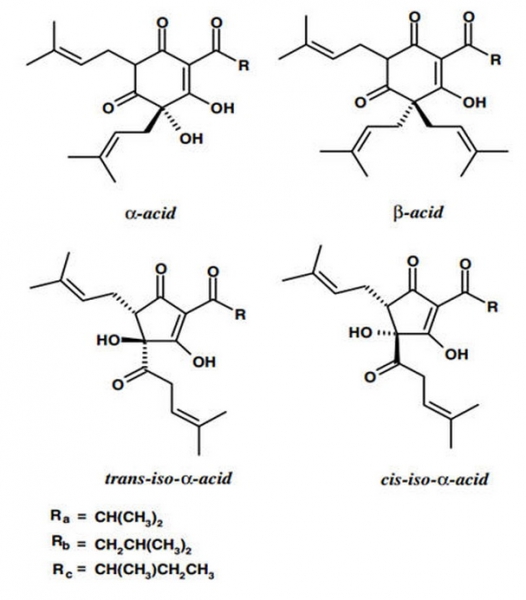

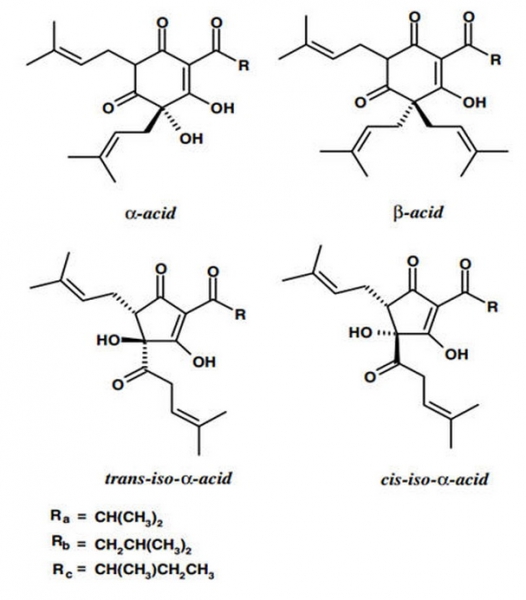

Molecular diagram of hop bitter acids. (Vanderhaegen et. al. Food Chemistry. (2006). 357381.)

Why do high ABV beers age well? Alcohol is protective against age, in people and in beer. Generally, it is recommended that only beers >8% ABV be aged, and that beers >10% almost require aging. A high ABV beer is more resistant to contamination and spoilage by wild yeast or bacteria, thereby allowing the beer to sit for extended periods of time. Chemically speaking, ethanol in beer is an excellent scavenger of reactive oxygen species. Interestingly, so are residual sugars. A high ABV beer containing some dextrans will age better than its counterpart with reduced ABV and dextrans. As oxygen finds its way into your beer, either because you were not careful or just due to natural diffusion, it can react with metals (iron and copper from the water and malts) and form reactive oxygen species. Before aging, most high ABV beers are described as "hot" or "solventy" due to the high concentration of ethanol (and other alcohols such as fusels). Over time, the reactions between reactive oxygen and ethanol in beer results in the generation of flavorful fruity esters and a smoothing of the hot flavors. In some instances, depending on the oxygen content, an inappropriate conversion of ethanol to acetaldehyde then acetic acid can occur. Directly after fermentation, the presence and eventual disappearance of acetaldehyde is an example of when this "aging out" process can occur. Very fresh beer, or maybe better described as very new beer, can have an apparent apple flavor. The beer is sometimes described as "green" for two reasons: green as in young and inexperienced, and green as in green-apple flavored. Acetaldehyde is the chemical responsible for this flavor. During fermentation, yeast metabolizes sugar into ethanol with acetaldehyde as an intermediate. A high level of acetaldehyde in green beer is due to an incomplete fermentation. Allowing the beer to condition or age allows the yeast to complete their metabolism. However this process is different from the conversion of ethanol back to acetaldehyde, which can happen during extended aging.

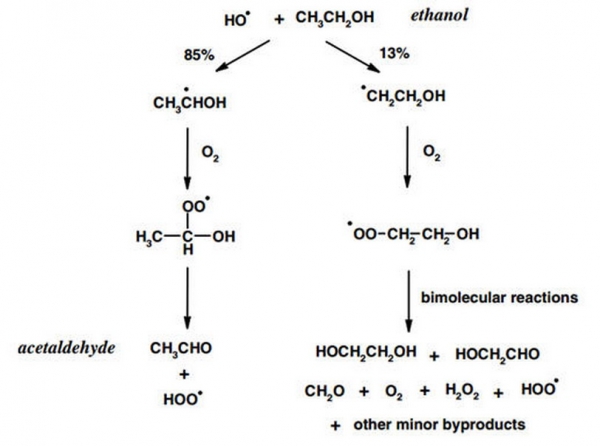

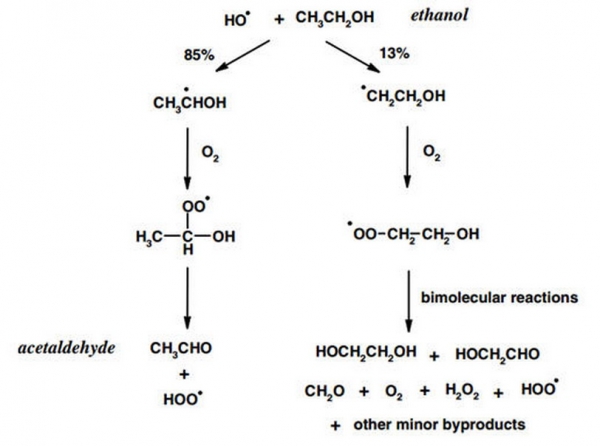

Reaction of ethanol and reactive oxygen species in beer (Andersen and Skibsten 1998)

Last but not least is yeast. Many of the aging process I have described are dependent on active yeast in the aging beer. Thus, filtered or pasteurized beer tends to not age as well as beer containing yeast. Primarily, you must choose a yeast that can handle the ABV of your beer and complete fermentation with the desired level of attenuation. Of equal importance, perhaps, is the flavor profile produced by the yeast during fermentation. Many long-aging beers are produced with ester-heavy yeasts. These (often fruity) esters produced during fermentation can undergo oxidation during the aging process and produce dried-fruit type flavors which complement the sweet, malty flavors in aged beer. For example, the ester isoamyl acetate (banana) produced during fermentation by many Belgian yeasts actually decreases over time in aged beer, while the esters gamma-hexalactone and gamma-nonalactone (peachy, fruity) increase over time.

Coming soon: The effects of temperature and oxygen on aging performance.

We have all heard the rules for selecting a beer for aging: high ABV and low hops, dark-colored, imperial, etc. Really though, you can choose to age any beer. But why do some beers deteriorate deliciously while others degenerate disastrously? While the focus here is primarily post-fermentation, we can start with the components of particular styles that allow for better aging performance.

The storage conditions influence the speed and extent of the aging reactions that occur in beer, as mentioned before (Part 1). However, the concentration of the precursor chemicals involved in these reactions will also influence their progression. These precursors come from our choice of ingredients, and process variables (oxygenation, temperature, etc). Regardless of the particular style, a brewer must use well-practiced techniques with regard to sanitation, and choose fresh, high-quality ingredients. The best practice is to avoid generating off-flavor associated compounds from the start by removing chlorine/chloramine from your water, managing fermentation temperature, and avoiding oxygen and microbes. Rarely, does an off-flavor discovered in a fresh beer "age out" over time. However, this "aging out" can happen in certain instances, which I will discuss later.

Change in sensory perception of lager over time. Note transition from estery and bitter to sweet and papery over time. (Wu et. al. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2011, 12(9), 6089-6103)

Why do darkly colored beers age better than lightly colored beers? Generally, this has to do with the robustness and composition of the flavors. Darker beers are made from dark, roasted malts. These malts provide many flavorful volatile compounds. When brewing with these malts, we depend on a particular reaction to develop the sought after flavors: the Maillard reaction. The Maillard reaction is a non-enzymatic combination between an amino acid (from protein) and sugar (from mashing). Maillard reactions occur during malting and the boil, producing a huge diversity of products that contribute to flavor, and in particular, melanoidins.

Melanoidins form through a wide variety of chemical rearrangement and recombination of the Maillard products, resulting in darkly colored nitrogen based compounds that provide an intense malty character (some are also antioxidants and antimicrobials!). During aging, small products of the Maillard reaction can polymerize to form larger compounds with new flavors. In beers with a high percentage of dark malts, a higher proportion of particular flavor active compounds (carbonyls, Strecker aldehydes, furfural alcohols, and Maillard reaction intermediates), provide significant antioxidant capability. Together, many of these compounds are associated with staling in light colored beers, but in darkly colored beers, they provide a sweet and malty impression and enhance long-term flavor stability. The aging process of dark beers is characterized by the development of burnt, alcoholic, caramel, liquorice and astringent flavors. These strong flavors mask the evolution of stale flavors that is occurring concurrently. A word of caution though: The (often) higher acidity from roasted malts is hard on the yeast remaining in the beer during aging. This can result is meaty/soy sauce flavors as the yeast dies.

Why shouldn't I age hoppy beers? You can, of course. But why would you? Even in the time it takes to finish a keg or case of bottles of your house IPA, most people can appreciate that the hop aroma (in particular) fades very quickly. The flavor eventually goes too. Moreover, a beer that is not highly hopped will be less likely to develop stale off-flavors. Bitter acids from hops (the iso-alpha, alpha, and beta acids) are quickly broken down, mostly due to oxidative processes. This degradation results in a decrease in bitterness (recall the Dalgliesh chart from part 1), but also in the formation of new compounds. These new compounds include a variety of carbonyls like (E)2-nonenal (stale), acetone (solventy), butanol and propanol (alcoholic/solventy), and butyric and propionic acid (cheesey/sulfur/sweaty). Again, I need to point out, that while these processes are likely occurring in an aged, hop-forward beer, it does not mean that these flavors are always detectable, nor considered off-flavors when the total flavor profile of the beer is considered. Regardless of the changes or flavors, you lose more than you gain when you age hoppy beers due to the abundance of precursor chemicals potentially resulting in off-flavors after degradation. A way to avoid some of these changes is to use hops with a high proportion of beta-acids (Lupulone, Colupulone, Adlupulone) like Amarillo or Galena. The beta-acids tend to maintain their bitterness over time and can age into fruity flavors as they degrade.

Molecular diagram of hop bitter acids. (Vanderhaegen et. al. Food Chemistry. (2006). 357381.)

Why do high ABV beers age well? Alcohol is protective against age, in people and in beer. Generally, it is recommended that only beers >8% ABV be aged, and that beers >10% almost require aging. A high ABV beer is more resistant to contamination and spoilage by wild yeast or bacteria, thereby allowing the beer to sit for extended periods of time. Chemically speaking, ethanol in beer is an excellent scavenger of reactive oxygen species. Interestingly, so are residual sugars. A high ABV beer containing some dextrans will age better than its counterpart with reduced ABV and dextrans. As oxygen finds its way into your beer, either because you were not careful or just due to natural diffusion, it can react with metals (iron and copper from the water and malts) and form reactive oxygen species. Before aging, most high ABV beers are described as "hot" or "solventy" due to the high concentration of ethanol (and other alcohols such as fusels). Over time, the reactions between reactive oxygen and ethanol in beer results in the generation of flavorful fruity esters and a smoothing of the hot flavors. In some instances, depending on the oxygen content, an inappropriate conversion of ethanol to acetaldehyde then acetic acid can occur. Directly after fermentation, the presence and eventual disappearance of acetaldehyde is an example of when this "aging out" process can occur. Very fresh beer, or maybe better described as very new beer, can have an apparent apple flavor. The beer is sometimes described as "green" for two reasons: green as in young and inexperienced, and green as in green-apple flavored. Acetaldehyde is the chemical responsible for this flavor. During fermentation, yeast metabolizes sugar into ethanol with acetaldehyde as an intermediate. A high level of acetaldehyde in green beer is due to an incomplete fermentation. Allowing the beer to condition or age allows the yeast to complete their metabolism. However this process is different from the conversion of ethanol back to acetaldehyde, which can happen during extended aging.

Reaction of ethanol and reactive oxygen species in beer (Andersen and Skibsten 1998)

Last but not least is yeast. Many of the aging process I have described are dependent on active yeast in the aging beer. Thus, filtered or pasteurized beer tends to not age as well as beer containing yeast. Primarily, you must choose a yeast that can handle the ABV of your beer and complete fermentation with the desired level of attenuation. Of equal importance, perhaps, is the flavor profile produced by the yeast during fermentation. Many long-aging beers are produced with ester-heavy yeasts. These (often fruity) esters produced during fermentation can undergo oxidation during the aging process and produce dried-fruit type flavors which complement the sweet, malty flavors in aged beer. For example, the ester isoamyl acetate (banana) produced during fermentation by many Belgian yeasts actually decreases over time in aged beer, while the esters gamma-hexalactone and gamma-nonalactone (peachy, fruity) increase over time.

Coming soon: The effects of temperature and oxygen on aging performance.

![Craft A Brew - Safale BE-256 Yeast - Fermentis - Belgian Ale Dry Yeast - For Belgian & Strong Ales - Ingredients for Home Brewing - Beer Making Supplies - [3 Pack]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/51bcKEwQmWL._SL500_.jpg)