So I've been making invert sugar for years following the recipe on the AHA website.

https://www.homebrewersassociation.org/beer-food/invert-syrups-making-simple-sugars-complex-beers/

According to this, temperature and color are directly proportional. Basically if you want invert #3 you just heat it to 300F and you're done.

I recently found Ron Pattinsons recipe and many online forum posts about needing to both neutralize the acid and hold it at a temperature for a length of time. Ron says to hold it at 240F for about 3.5 hours to get to invert #3.

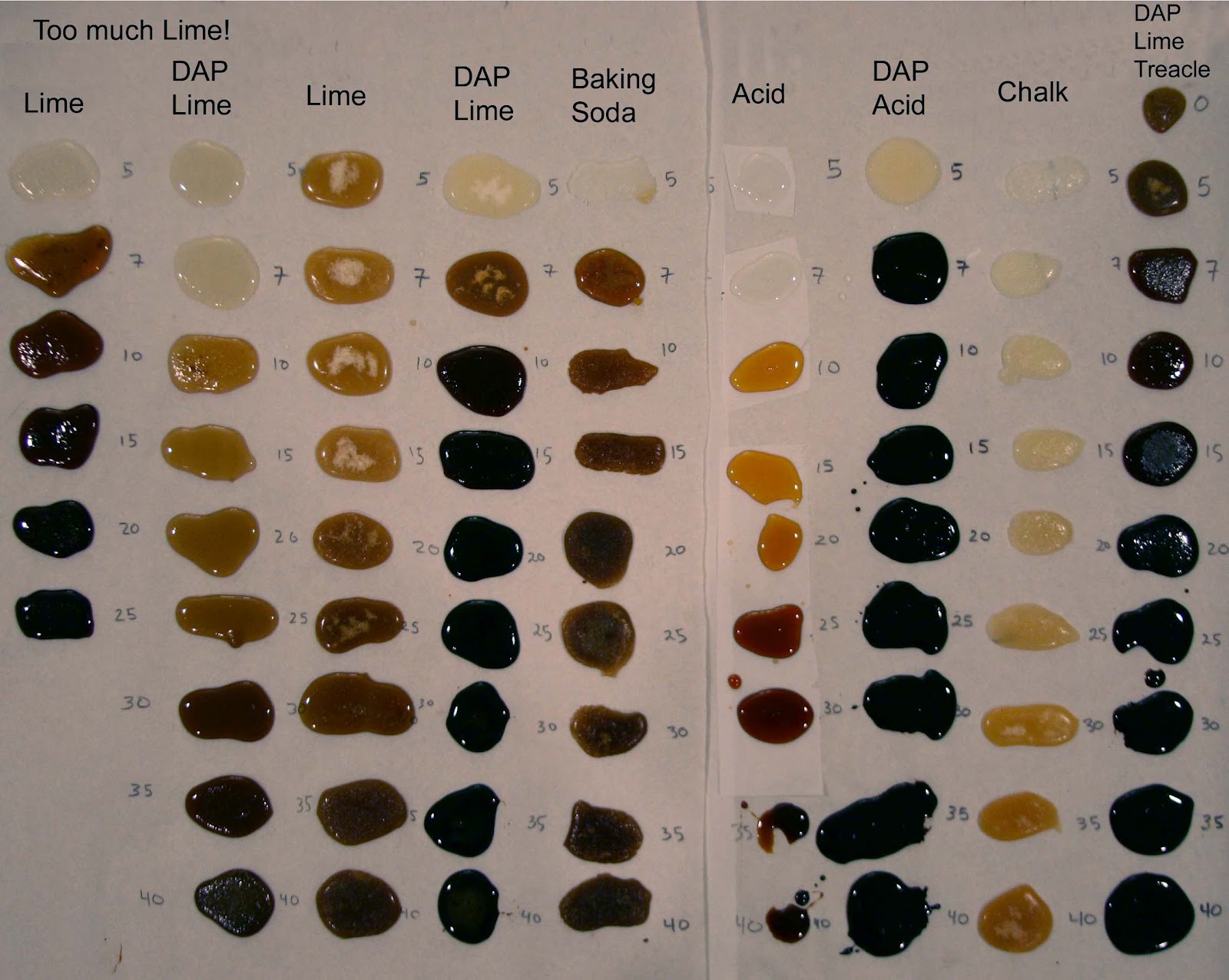

I recognize that the boiling temperature of a sugar solution is directly proportional to the water content. So the AHA version seems to just be reducing water and not actually achieving any substantial color change. In fact I made a batch yesterday and I took a color sample every 10 degrees from 250F to 300F and I could barely see any difference between the highest and lowest samples.

So it seems that Ron's description is definitely the way to achieve darker colors, and his method will maintain the water content around 20% so it can actually be poured more easily.

Does anyone know why there's two completely different methods circulating and the chemistry of what's actually happening between the two? I know they both produce invert, but they are drastically different in how they approach color.

I'm pretty sure the AHA version is just driving off water and any color change is coming from caramelization, whereas Ron's method is producing maillard products, but I'm not sure.

It's disappointing that there's such incorrect information published on the AHA website as fact too.

https://www.homebrewersassociation.org/beer-food/invert-syrups-making-simple-sugars-complex-beers/

According to this, temperature and color are directly proportional. Basically if you want invert #3 you just heat it to 300F and you're done.

I recently found Ron Pattinsons recipe and many online forum posts about needing to both neutralize the acid and hold it at a temperature for a length of time. Ron says to hold it at 240F for about 3.5 hours to get to invert #3.

I recognize that the boiling temperature of a sugar solution is directly proportional to the water content. So the AHA version seems to just be reducing water and not actually achieving any substantial color change. In fact I made a batch yesterday and I took a color sample every 10 degrees from 250F to 300F and I could barely see any difference between the highest and lowest samples.

So it seems that Ron's description is definitely the way to achieve darker colors, and his method will maintain the water content around 20% so it can actually be poured more easily.

Does anyone know why there's two completely different methods circulating and the chemistry of what's actually happening between the two? I know they both produce invert, but they are drastically different in how they approach color.

I'm pretty sure the AHA version is just driving off water and any color change is coming from caramelization, whereas Ron's method is producing maillard products, but I'm not sure.

It's disappointing that there's such incorrect information published on the AHA website as fact too.