Are Bass Ale and Whitbread considered bitters? For a long time, I've been wanting to try a bitter, but if Bass and Whitbread are bitters, I'm already familiar.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Bass and Whitbread: Bitters?

- Thread starter Clint Yeastwood

- Start date

Help Support Homebrew Talk:

This site may earn a commission from merchant affiliate

links, including eBay, Amazon, and others.

worlddivides

Well-Known Member

Hm. I guess those are both strong bitters. Apparently Bass Pale Ale and Whitbread Pale Ale are both "Strong Bitters." It's confusing because they're English Pale Ales, which also happen to be "bitters" (apparently the brewers originally called them "pale ales" and the patrons called them "bitters"). Fullers London Pride and ESB are other examples of bitters.

Honestly, the naming is really confusing...

Edit: Even found this:

https://www.bjcp.org/beer-styles/8c-extra-specialstrong-bitter-english-pale-ale/

Honestly, the naming is really confusing...

Edit: Even found this:

https://www.bjcp.org/beer-styles/8c-extra-specialstrong-bitter-english-pale-ale/

Last edited:

I never considered the possibility that these companies might have multiple products. Back in the Eighties, we just went into bars and said "Bass" or "Whitbread." Wikipedia seems to think Bass's only export to the US was Bass Pale Ale.

As I recall, Whitbread was pretty similar to Bass, but it had a kind of doggy aspect to the aroma. That's the only way I can describe it. Slightly similar to the smell of a wet dog. Not strong enough to be a real problem.

Maybe I can find ESB at the local Whole Foods clone. Thanks.

As I recall, Whitbread was pretty similar to Bass, but it had a kind of doggy aspect to the aroma. That's the only way I can describe it. Slightly similar to the smell of a wet dog. Not strong enough to be a real problem.

Maybe I can find ESB at the local Whole Foods clone. Thanks.

worlddivides

Well-Known Member

Whitbread used to be the biggest brewery in the world, and considering small breweries also make quite a few different beers, it only makes sense that much bigger ones like Whitbread (though it's pretty tiny now compared to how big it was in the 1800s or early 1900s) and Bass would have a pretty wide variety of beers. I think they each make the whole spectrum of bitters/pale ales: ordinary, best, and strong.

Fullers London Pride and ESB are also relatively easy to find on tap at English pubs in the US. I prefer them quite a bit over Bass or Whitbread, personally. Either way, you should be able to find them at a relatively large liquor store like BevMo or Total Wine & More.

Fullers London Pride and ESB are also relatively easy to find on tap at English pubs in the US. I prefer them quite a bit over Bass or Whitbread, personally. Either way, you should be able to find them at a relatively large liquor store like BevMo or Total Wine & More.

Old Speckled Hen is another one to seek out, and considered a bitter. You can find it in package stores, and on draught in British-style pubs.

I am watching a video by an English guy who seems to consider himself an expert, and he says Bass Pale Ale is "very much a bitter."

$719.00

$799.00

EdgeStar KC2000TWIN Full Size Dual Tap Kegerator & Draft Beer Dispenser - Black

Amazon.com

![Craft A Brew - Safale S-04 Dry Yeast - Fermentis - English Ale Dry Yeast - For English and American Ales and Hard Apple Ciders - Ingredients for Home Brewing - Beer Making Supplies - [1 Pack]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/41fVGNh6JfL._SL500_.jpg)

$6.95 ($17.38 / Ounce)

$7.47 ($18.68 / Ounce)

Craft A Brew - Safale S-04 Dry Yeast - Fermentis - English Ale Dry Yeast - For English and American Ales and Hard Apple Ciders - Ingredients for Home Brewing - Beer Making Supplies - [1 Pack]

Hobby Homebrew

$22.00 ($623.23 / Ounce)

AMZLMPKNTW Ball Lock Sample Faucet 30cm Reinforced Silicone Hose Secondary Fermentation Homebrew Kegging joyful

无为中南商贸有限公司

$176.97

1pc Commercial Keg Manifold 2" Tri Clamp,Ball Lock Tapping Head,Pressure Gauge/Adjustable PRV for Kegging,Fermentation Control

hanhanbaihuoxiaoshoudian

$49.95 ($0.08 / Fl Oz)

$52.99 ($0.08 / Fl Oz)

Brewer's Best - 1073 - Home Brew Beer Ingredient Kit (5 gallon), (Blueberry Honey Ale) Golden

Amazon.com

$20.94

$29.99

The Brew Your Own Big Book of Clone Recipes: Featuring 300 Homebrew Recipes from Your Favorite Breweries

Amazon.com

$44.99

$49.95

Craft A Brew - Mead Making Kit – Reusable Make Your Own Mead Kit – Yields 1 Gallon of Mead

Craft a Brew

$479.00

$559.00

EdgeStar KC1000SS Craft Brew Kegerator for 1/6 Barrel and Cornelius Kegs

Amazon.com

$76.92 ($2,179.04 / Ounce)

Brewing accessories 1.5" Tri Clamp to Ball Lock Post Liquid Gas Homebrew Kegging Fermentation Parts Brewer Hardware SUS304 Brewing accessories(Gas Hose Barb)

chuhanhandianzishangwu

$7.79 ($7.79 / Count)

Craft A Brew - LalBrew Voss™ - Kveik Ale Yeast - For Craft Lagers - Ingredients for Home Brewing - Beer Making Supplies - (1 Pack)

Craft a Brew

$53.24

1pc Hose Barb/MFL 1.5" Tri Clamp to Ball Lock Post Liquid Gas Homebrew Kegging Fermentation Parts Brewer Hardware SUS304(Gas MFL)

Guangshui Weilu You Trading Co., Ltd

$53.24

1pc Hose Barb/MFL 1.5" Tri Clamp to Ball Lock Post Liquid Gas Homebrew Kegging Fermentation Parts Brewer Hardware SUS304(Liquid Hose Barb)

yunchengshiyanhuqucuichendianzishangwuyouxiangongsi

$33.99 ($17.00 / Count)

$41.99 ($21.00 / Count)

2 Pack 1 Gallon Large Fermentation Jars with 3 Airlocks and 2 SCREW Lids(100% Airtight Heavy Duty Lid w Silicone) - Wide Mouth Glass Jars w Scale Mark - Pickle Jars for Sauerkraut, Sourdough Starter

Qianfenie Direct

$58.16

HUIZHUGS Brewing Equipment Keg Ball Lock Faucet 30cm Reinforced Silicone Hose Secondary Fermentation Homebrew Kegging Brewing Equipment

xiangshuizhenzhanglingfengshop

worlddivides

Well-Known Member

I am watching a video by an English guy who seems to consider himself an expert, and he says Bass Pale Ale is "very much a bitter."

As far as I can tell, in the UK, all pale ales are "bitters." It also seems to be a terminology difference. Like I mentioned above, originally the breweries called them "pale ales" but the patrons called them "bitters" and you can find both "pale ales" and "bitters" used interchangeably in the names of beers. Apparently this term was created to contrast with "milds" (which is the term used by both the breweries and the patrons).

I personally had thought that bitters were a subset of pale ales, and if you look up all these "bitters" on American beer websites, you'll usually see them listed as "English Pale Ale." So it's actually bitter = pale ale and pale ale = bitter.

Old Speckled Hen is another one to seek out, and considered a bitter. You can find it in package stores, and on draught in British-style pubs.

That beer was on draught in my town back in the '80s when we actually had a pub - owned by a cousin of my Irish wife - and it was my introduction to British beer. I quite enjoyed it, as well as some of the other English beers they had on tap, including a winter warmer that may have been from Samuel Smith...

Cheers!

So I have had bitter, and I thought it was pretty good. Like a more sessiony, non-American IPA without iron-fisted, throat-punching dry-hopping.

I wonder if the mild nature of many British beers comes from the fact that in the old days, a lot of British workers wanted to hammer a lot of beers every day without getting hammered, themselves. I read that Guinness, which is British-adjacent, was developed so workers could have a very light, tasty beer that was low in alcohol.

The dude in the video doesn't like IPA with American-style citrusy hops. That's amazing. There are WAY too many IPA's, and it seems like commercial brew bros with no imagination are determined to drive everything else off the market, but IPA is a fantastic style. I'm surprised anyone who likes Bass would reject it. But maybe the IPA's he has access to are clumsy copies of American IPA's.

The local Whole Foods clone has an immense selection of beers, but IPA's take up so much room, some things are left out. I have never seen a saison or a Kolsch there, except for a phony Kolsch that was probably created to attract people who are afraid to stray far from Bud.

If I could tell them what to stock, I'd tell them to cut back to 15 IPA's and get rid of the fake beers that are actually tamed so they don't offend Bud drinkers.

I wonder if the mild nature of many British beers comes from the fact that in the old days, a lot of British workers wanted to hammer a lot of beers every day without getting hammered, themselves. I read that Guinness, which is British-adjacent, was developed so workers could have a very light, tasty beer that was low in alcohol.

The dude in the video doesn't like IPA with American-style citrusy hops. That's amazing. There are WAY too many IPA's, and it seems like commercial brew bros with no imagination are determined to drive everything else off the market, but IPA is a fantastic style. I'm surprised anyone who likes Bass would reject it. But maybe the IPA's he has access to are clumsy copies of American IPA's.

The local Whole Foods clone has an immense selection of beers, but IPA's take up so much room, some things are left out. I have never seen a saison or a Kolsch there, except for a phony Kolsch that was probably created to attract people who are afraid to stray far from Bud.

If I could tell them what to stock, I'd tell them to cut back to 15 IPA's and get rid of the fake beers that are actually tamed so they don't offend Bud drinkers.

I mean, technically, yeah... It's complicated.Are Bass Ale and Whitbread considered bitters? For a long time, I've been wanting to try a bitter, but if Bass and Whitbread are bitters, I'm already familiar.

It breaks my heart to say this, but after several absorptions into multinational brewing conglomerates, they're as much of a bitter as Bud is a pilsner. The Bass that I used to adore in the early 90's was a pale representation of what it used to be, I'm told, but at least it was brewed in the UK. The N. American-brewed crap they sell now is kinda awful. I think MaxStout's recommendation of Old Speckled Hen is a good one, but understand that it's a style that just doesn't travel very well. It's a style that really does need to be consumed fresh.

As a US brewer, I'd suggest simply making your own if you want to learn what bitter is all about. After decades of chasing the bitter dragon, I've learned that simplicity and the right yeast trumps all when it comes to a good bitter.

Yeast plays an important role in a decent bitter and you can't go wrong with the Fullers strain. The best example is Imperial Pub, it produces a great bitter and it's among the simplest UK yeasts to use. There's nothing fussy about it. Stay away from dried yeasts. Unfortunately, they all suck. The Yorkshire strains, Ringwood or Timothy Taylor, are also good options, but they're a bit more fussy to use. I'd start out with the Fullers strain.

In terms of grist, you absolutely need to use a full-throated UK pale ale malt, I like Crisp or Warminster. You can use UK crystal malts, but I've learned that 2.5%-5% (4oz) is about all you need, but straight UK base malt is perfectly fine. Stay away from recipes that use multiple C-malts, wheat, or roast malts (unless it's a tiny percentage used as a colorant--I used to do that, but I prefer not to color my bitters anymore).

In terms of hops, initially start with East Kent Goldings (EKGs) or Fuggles and split your IBUs evenly between your 60 and 30min additions. Use .25-.5oz as kegging hops--not dry hops. They go in the serving keg. Relax, they will not get grassy. They were bred for this.

Be assertive with your gypsum addition, but don't go overboard. Your bitter should be noticeably dry, even a touch minerally, but you don't want it to taste like Alka-Seltzer. As with all things bitter, use restraint and look for balance.

Brewed correctly, a good bitter is much akin to Germany's Helles, it's all about balance. Despite it's name, bitter is not a bitter beer (at least not by US standards). It's perfectly okay to tip a bit toward the malt or the hops, but maintain balance. Unlike a Helles, though, you want tangible yeast esters and they should also be in balance with the malt and hops. You want them to be prominant, but not dominant as in a Belgian. Pub pitched at 66F, then allowed to free rise to 68F to half gravity, then allowed to free rise again to 70F to finish will get you an ester profile that matches the style. If your three key ingredients, hops, malt, and yeast, aren't complementing each other, you're doing it wrong.

Above all else, don't make your bitter sweet. US brewers love doing that because the examples that we get imported from the UK are frequently age and travel damaged beers.

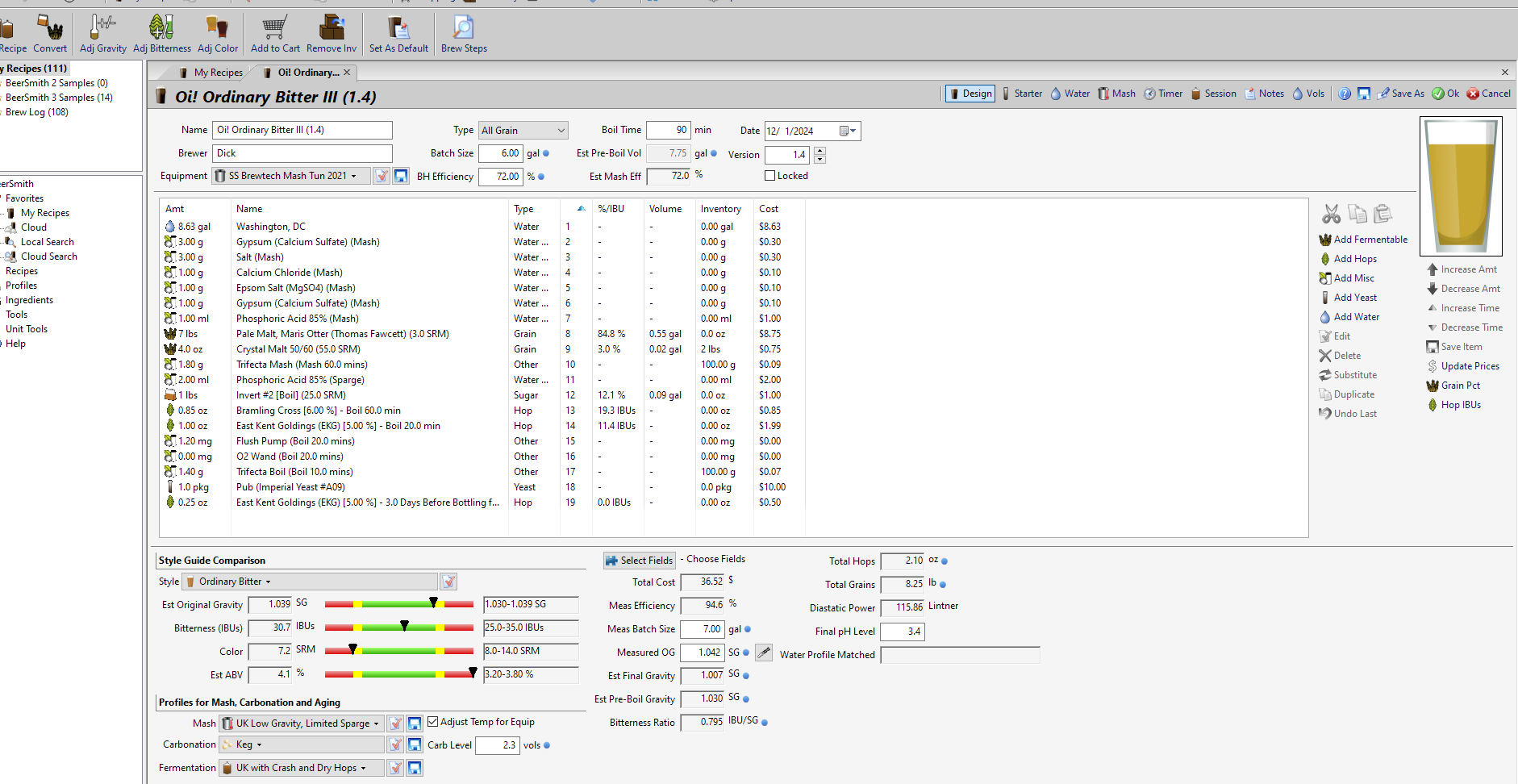

Here's my current Ordinary Bitter. After decades of frustration, I'm actually kinda okay with this. It doesn't suck and I'm not sure how to make it better. It uses invert sugar, which you can learn about here. Don't be intimidated, it's cheap and stupidly easy to do. If you don't want to mess around with invert, just use an extra pound of Otter.

I hope you found this useful. It took me decades to get here, but I'm currently okay with my ordinary bitter. I'm still trying to wrap my head around that because it's the style that I've spent the most time being pissed off at.

worlddivides

Well-Known Member

IPAs are one of my favorite styles, but I definitely agree that it's a bit excessive with 80% of the beers somewhere being some variation of IPA. As much as I love the style, I also want stouts, sours, saisons, wild ales, brown ales, and on and on.

The "ordinary bitter" is the weakest style of bitter and is typically 3.2% to 3.8% and milds tend to be even lower ABV starting around 2.8%, and I tend to think of them as the very definition of "session" beers that are designed to just drink a ton of them without getting absolutely wasted.

The "ordinary bitter" is the weakest style of bitter and is typically 3.2% to 3.8% and milds tend to be even lower ABV starting around 2.8%, and I tend to think of them as the very definition of "session" beers that are designed to just drink a ton of them without getting absolutely wasted.

I'd probably disagree with this here; wheat, either in torrefied or malted form, is very much an acceptable (and IMO desirable) element of a bitter grist, at quantities under 5%, for both head retention and body.Stay away from recipes that use multiple C-malts, wheat, or roast malts (unless it's a tiny percentage used as a colorant--I used to do that, but I prefer not to color my bitters anymore).

The wider "English bitter" base recipe of specifically British pale malt, specifically British crystal malts (though I would say "up to 7%"), a British yeast and Fuggle/EKG is broadly on the money.

-Edit: speeling

Last edited:

That sums it all up!I mean, technically, yeah... It's complicated.

It breaks my heart to say this, but after several absorptions into multinational brewing conglomerates, they're as much of a bitter as Bud is a pilsner. The Bass that I used to adore in the early 90's was a pale representation of what it used to be, I'm told, but at least it was brewed in the UK. The N. American-brewed crap they sell now is kinda awful. I think MaxStout's recommendation of Old Speckled Hen is a good one, but understand that it's a style that just doesn't travel very well. It's a style that really does need to be consumed fresh.

As a US brewer, I'd suggest simply making your own if you want to learn what bitter is all about. After decades of chasing the bitter dragon, I've learned that simplicity and the right yeast trumps all when it comes to a good bitter.

Yeast plays an important role in a decent bitter and you can't go wrong with the Fullers strain. The best example is Imperial Pub, it produces a great bitter and it's among the simplest UK yeasts to use. There's nothing fussy about it. Stay away from dried yeasts. Unfortunately, they all suck. The Yorkshire strains, Ringwood or Timothy Taylor, are also good options, but they're a bit more fussy to use. I'd start out with the Fullers strain.

In terms of grist, you absolutely need to use a full-throated UK pale ale malt, I like Crisp or Warminster. You can use UK crystal malts, but I've learned that 2.5%-5% (4oz) is about all you need, but straight UK base malt is perfectly fine. Stay away from recipes that use multiple C-malts, wheat, or roast malts (unless it's a tiny percentage used as a colorant--I used to do that, but I prefer not to color my bitters anymore).

In terms of hops, initially start with East Kent Goldings (EKGs) or Fuggles and split your IBUs evenly between your 60 and 30min additions. Use .25-.5oz as kegging hops--not dry hops. They go in the serving keg. Relax, they will not get grassy. They were bred for this.

Be assertive with your gypsum addition, but don't go overboard. Your bitter should be noticeably dry, even a touch minerally, but you don't want it to taste like Alka-Seltzer. As with all things bitter, use restraint and look for balance.

Brewed correctly, a good bitter is much akin to Germany's Helles, it's all about balance. Despite it's name, bitter is not a bitter beer (at least not by US standards). It's perfectly okay to tip a bit toward the malt or the hops, but maintain balance. Unlike a Helles, though, you want tangible yeast esters and they should also be in balance with the malt and hops. You want them to be prominant, but not dominant as in a Belgian. Pub pitched at 66F, then allowed to free rise to 68F to half gravity, then allowed to free rise again to 70F to finish will get you an ester profile that matches the style. If your three key ingredients, hops, malt, and yeast, aren't complementing each other, you're doing it wrong.

Above all else, don't make your bitter sweet. US brewers love doing that because the examples that we get imported from the UK are frequently age and travel damaged beers.

Here's my current Ordinary Bitter. After decades of frustration, I'm actually kinda okay with this. It doesn't suck and I'm not sure how to make it better. It uses invert sugar, which you can learn about here. Don't be intimidated, it's cheap and stupidly easy to do. If you don't want to mess around with invert, just use an extra pound of Otter.

View attachment 873559

I hope you found this useful. It took me decades to get here, but I'm currently okay with my ordinary bitter. I'm still trying to wrap my head around that because it's the style that I've spent the most time being pissed off at.

i too like a variety of beers but most people do not so the breweries are forced to conform to the demand or die. The competition is fierce. Even brew pubs have to limit what is on tap as a beer that isn't selling enough quantity ties up an otherwise profitable tap.IPAs are one of my favorite styles, but I definitely agree that it's a bit excessive with 80% of the beers somewhere being some variation of IPA. As much as I love the style, I also want stouts, sours, saisons, wild ales, brown ales, and on and on.

The "ordinary bitter" is the weakest style of bitter and is typically 3.2% to 3.8% and milds tend to be even lower ABV starting around 2.8%, and I tend to think of them as the very definition of "session" beers that are designed to just drink a ton of them without getting absolutely wasted.

With that in mind, I will try beers that I haven't brewed just to see if I like them or will try a highly hopped IPA because I like the taste and do not have the equipment to successfully brew them myself.

Eee. A favorite subject ... well related to a favorite subject.Are Bass Ale and Whitbread considered bitters? For a long time, I've been wanting to try a bitter, but if Bass and Whitbread are bitters, I'm already familiar.

I was bought up in a South Derbyshire village, "Ockbrook" population (then) <1000, four pubs (still exist?) selling Bass bitter, a couple sold Worthington (still Bass, but always thought it was inferior), and "Whitbread" keg cwap too. So, I'm not talking about Whitbread no-more.

All gone! Bass exited the brewery business and Marston's (a once rival in nearby Burton-on-Trent ... you can see B-o-T from Ockbrook, over the fields that have been growing barley for malt, for ale and beer, for over four centuries) started making Bass bitter ... and recently Marstons followed Bass, and the brewing is under Carlsberg's control now ...

@Bramling Cross has posted a good summary, so I shan't clutter that up.

"Bitter" is very much a dying out word ... but not beer (they get called "amber ales" now). "Mild" is also dying out, but I'm a strong believer that many "morphed" into Bitter before succumbing to be the dark coloured stuff that's dying out ... the "morphing" is documented in the history of Wadworth's "6X", a once (100 years ago) "X-Ale" ("XXXX") or "Mild", but now a "Bitter" ( ... oops, sorry, I mean "Amber Ale"!).

worlddivides

Well-Known Member

I definitely get that. Sour ales and wild ales are among my absolute favorite beer styles, but you don't see them as often because A: a lot of people really hate them (like not just dislike them, but actively hate them, hence why when you do see them, they're often designed to be as accessible as possible either by sweetening them or arranging them around flavors that pretty much everyone likes such as lemon) and B: traditional sours and wild ales take a long time to make and can be costly, which is problematic if only a small number of people will buy them, so you're most likely to get something along the lines of a kettle sour.i too like a variety of beers but most people do not so the breweries are forced to conform to the demand or die. The competition is fierce. Even brew pubs have to limit what is on tap as a beer that isn't selling enough quantity ties up an otherwise profitable tap.

With that in mind, I will try beers that I haven't brewed just to see if I like them or will try a highly hopped IPA because I like the taste and do not have the equipment to successfully brew them myself.

Stouts are a lot more popular than sours, but it can be hard to call them "popular," really. My wife absolutely loves dark beers, but it's common to go to a tap room or brewery and there not be a single dark beer on tap. I went to a large bottle shop the other day, and in the section I frequent the most, out of about 40 different beers, there were only 2 dark beers (an imperial stout and a dessert stout).

Outside of IPAs and pale ales, I do see a decent amount of lagers and an okay amount of saisons (usually dry-hopped or just using New World hops).

If you really want to do a deep dive into English Bitter/Pale Ale and the Whitbread brewery spend some time browsing Ron Pattinson's blog called Shut Up About Barclay Perkins. Barclay Perkins being Whitbread's main rival. Together they were the worlds largest producers of beer in the world. Their porter output alone was measured in the millions of barrels.

I see what you did there.The Bass that I used to adore in the early 90's was a pale representation of what it used to be

I think the Bass that I enjoyed in the 80's was still the real thing, but probably well past its prime by the time we got to drink it.

One of these days I'm going to try a bitter with the "English Pale Malt" from my local craft maltster. It too may be a pale imitation of the real thing but I like the idea of representing the local terroir in my brews. Aside from that, it will be pretty close to your recipe.Here's my current Ordinary Bitter...

I said I wouldn't talk about "Whitbread" no-more. But @kevin58 makes a good point: "Whitbread" is probably No.1 for pulling historic recipes (pre-WWII) out of Ron Pattinson's collections. So; I'll talk about them a bit.If you really want to do a deep dive into English Bitter/Pale Ale and the Whitbread brewery spend some time browsing Ron Pattinson's blog called Shut Up About Barclay Perkins. Barclay Perkins being Whitbread's main rival. Together they were the worlds largest producers of beer in the world. Their porter output alone was measured in the millions of barrels.

Near as I can tell from my browsing of Ron Pattinson's blog @kevin58 linked, the brits were somewhere between "very cost conscious" to downright cheap. They may still be today, I don't know. But everything seemed geared toward hitting the optimal $/alcohol value which generally floated around 2-4%.I wonder if the mild nature of many British beers comes from the fact that in the old days, a lot of British workers wanted to hammer a lot of beers every day without getting hammered, themselves. I read that Guinness, which is British-adjacent, was developed so workers could have a very light, tasty beer that was low in alcohol.

I missed that snippet @Agent posted ...

As long as you don't go back too far for the "old days": Pre WWI a "mild" (or its precursor, as Ron P. writes of, an "X-ale") wasn't weak! Neither was Guinness "Stout" ... there is a WWII-era version of Guinness Stout still available ... John Martin's Special Export ... which is a version for the Belgian market but available widely now (it is NOT the same as the Nigerian version!). It was based on earlier versions of Guinness Stout (they were a Porter brewer primarily), and at 8% it certainly isn't "weak".I wonder if the mild nature of many British beers comes from the fact that in the old days, a lot of British workers wanted to hammer a lot of beers every day without getting hammered, themselves. I read that Guinness, which is British-adjacent, was developed so workers could have a very light, tasty beer that was low in alcohol.

duncan_disorderly

Well-Known Member

I think the desperation to categorise beers creates problems. I started out drinking Boddingtons bitter in Lancashire in the 70s and not much else. I then went to University in Nottingham and drank bitters that were completely different. Shipstones bitter, Home bitter, Mansfield bitter and Kimberley bitter, among others. Marstons beers like Pedigree and Merry Monk. Bass ales. Burton is not far from Nottingham.

Brewers assemble beers from the available ingredients in different combinations and quantities. Then they give them a name. They may call a beer and IPA when another brewery names a very similar beer a bitter or something else. Boddingtons bitter was apparently considered to be an IPA by the brewery. It was a straw colour, and might be considered as a golden ale now. What is a golden ale? It's a bitter with a pale golden colour, using pale crystal, or no crystal. Bitters vary quite a bit. If you know what a variety of beer is that use English ingredients taste like, I suspect that's all you really need to know. Beers vary. They vary more when the ingredient sources are radically different. Probably.

Brewers assemble beers from the available ingredients in different combinations and quantities. Then they give them a name. They may call a beer and IPA when another brewery names a very similar beer a bitter or something else. Boddingtons bitter was apparently considered to be an IPA by the brewery. It was a straw colour, and might be considered as a golden ale now. What is a golden ale? It's a bitter with a pale golden colour, using pale crystal, or no crystal. Bitters vary quite a bit. If you know what a variety of beer is that use English ingredients taste like, I suspect that's all you really need to know. Beers vary. They vary more when the ingredient sources are radically different. Probably.

Read his blog a bit more and you'll understand the three reasons why ... Tax, tax and ... err ... tax?... Ron Pattinson's blog @kevin58 linked, the brits were somewhere between "very cost conscious" to downright cheap ...

The Brits aren't cheap! We are very ... ermm ... Okay, we are cheap.

The month of May is coming and back in the '80's we'd say, "Make mine a mild," May being mild month. And, yes, I would love to brew a decent bitter. Many of the names you mentioned above remind me of working at beer festivals, such a treat and such a variety. For now, we still brew milds because we love to drink beer (not lager).

Agreed, this is a lovely yeast.The best example is Imperial Pub

I hope this helps, here's a page from my upcoming book "British Ales"

BITTER & PALE ALE ~ WHAT IS THE DIFFERENCE?

Question: What is the difference between a British bitter, special bitter, pale ale, amber ale, IPA? Answer: They are all pale ales based on pale malt that only differ in their alcohol content.

In the book “Amber, Gold and Black: The History of Britain’s Great Beers” by Martyn Cornell it states: “Let’s begin with the insistence that “pale ale” and “bitter” are different products. From the moment that bitter beers started to become popular in Britain, around the beginning of the 1840s, “bitter beer” and “pale ale” were used by brewers and commentators as synonyms. There never was any difference between the two.”

Lately, the fashion has been to call these beers “Amber Ales” as marketing departments discover that young people don’t like bitter beer or in fact dry beer as in “dry hopped”. Go figure!

Why did “pale ale” come to be appended as a name mostly to the bottled version of bitter? Because generally in the 19th century brewers called the beer in the brewery “pale ale”, and that’s the name they put on their bottle labels, but in the pub, drinkers of the cask version called this new drink “bitter”, to differentiate it from the older, sweeter, but still (then) pale Mild ales. India Pale Ales were pale ales that contained more bittering hops and could be lower in alcohol than contemporary pale and sweeter Mild ales.

Just so you know, the term Mild was originally used to signify a young beer (as opposed to a keeping ale which could be 12 months old or more before serving). Porter was originally a blend of mild and keeping ale and popular with London porters who loaded and unloaded vessels anchored in the river and who carried parcels, letters and messages about the streets, transported heavy items from warehouses to shops, and so on.

So, English pale ales are a single, evolving continuum of beer style with some examples barely reaching 3.5 percent alcohol by volume ABV and others climbing to 6 percent ABV and higher. These beers also tend to have wonderful names such as Workie Ticket & Radgie Gadgie (Mordue Brewery), Old Hooky (Hook Norton Brewery), Pheasant Plucker (Hunters Brewery), and Old Speckled Hen (Greene King Brewery).

Built on a foundation of pale malt, English pale ales almost invariably feature a healthy measure of crystal malt, which adds caramel or toffee-like depth. Some examples also include a bit of chocolate malt or roasted barley and black malt, more for colour than flavour, and use maize or sugar adjuncts from time to time.

Hops are almost always of English origin. Floral, earthy East Kent Goldings hops are perhaps most closely associated with English pale ale, but minty, grassy Fuggle comes in a close second. Styrian Goldings are also used but Styrians are biologically Fuggles, not Goldings. Common bittering hops include Challenger, Northdown, and Target.

•

BITTER & PALE ALE ~ WHAT IS THE DIFFERENCE?

Question: What is the difference between a British bitter, special bitter, pale ale, amber ale, IPA? Answer: They are all pale ales based on pale malt that only differ in their alcohol content.

In the book “Amber, Gold and Black: The History of Britain’s Great Beers” by Martyn Cornell it states: “Let’s begin with the insistence that “pale ale” and “bitter” are different products. From the moment that bitter beers started to become popular in Britain, around the beginning of the 1840s, “bitter beer” and “pale ale” were used by brewers and commentators as synonyms. There never was any difference between the two.”

Lately, the fashion has been to call these beers “Amber Ales” as marketing departments discover that young people don’t like bitter beer or in fact dry beer as in “dry hopped”. Go figure!

Why did “pale ale” come to be appended as a name mostly to the bottled version of bitter? Because generally in the 19th century brewers called the beer in the brewery “pale ale”, and that’s the name they put on their bottle labels, but in the pub, drinkers of the cask version called this new drink “bitter”, to differentiate it from the older, sweeter, but still (then) pale Mild ales. India Pale Ales were pale ales that contained more bittering hops and could be lower in alcohol than contemporary pale and sweeter Mild ales.

Just so you know, the term Mild was originally used to signify a young beer (as opposed to a keeping ale which could be 12 months old or more before serving). Porter was originally a blend of mild and keeping ale and popular with London porters who loaded and unloaded vessels anchored in the river and who carried parcels, letters and messages about the streets, transported heavy items from warehouses to shops, and so on.

So, English pale ales are a single, evolving continuum of beer style with some examples barely reaching 3.5 percent alcohol by volume ABV and others climbing to 6 percent ABV and higher. These beers also tend to have wonderful names such as Workie Ticket & Radgie Gadgie (Mordue Brewery), Old Hooky (Hook Norton Brewery), Pheasant Plucker (Hunters Brewery), and Old Speckled Hen (Greene King Brewery).

Built on a foundation of pale malt, English pale ales almost invariably feature a healthy measure of crystal malt, which adds caramel or toffee-like depth. Some examples also include a bit of chocolate malt or roasted barley and black malt, more for colour than flavour, and use maize or sugar adjuncts from time to time.

Hops are almost always of English origin. Floral, earthy East Kent Goldings hops are perhaps most closely associated with English pale ale, but minty, grassy Fuggle comes in a close second. Styrian Goldings are also used but Styrians are biologically Fuggles, not Goldings. Common bittering hops include Challenger, Northdown, and Target.

•

You got the original meaning of Mild correct. The opposite which is aged beer would have also been "Stale". When researching beer history it is important to be aware of how much language has changed between then and now.I hope this helps, here's a page from my upcoming book "British Ales"

Just so you know, the term Mild was originally used to signify a young beer (as opposed to a keeping ale which could be 12 months old or more before serving).

Porter was originally a blend of mild and keeping ale and popular with London porters who loaded and unloaded vessels anchored in the river and who carried parcels, letters and messages about the streets, transported heavy items from warehouses to shops, and so on.

It sounds suspiciously like your definition of porter however comes from the misunderstood "three threads" story and/or a misinterpretation of the Obidiah Poundage letter. There is a pretty good accounting of those misunderstandings in this blog post: https://barclayperkins.blogspot.com/2007/08/barclay-perkins-tt.html FYI: Martyn Cornell agrees with Ron and he will release a book this June on the topic of Porter. Those misunderstandings all are the result of not being aware of those language changes.

Short answer:Yes

Long answer: Yes, but (tl:dr)

Long answer: Yes, but (tl:dr)

An Ankoù

Well-Known Member

I'm not sure if this is true or not, but I always understood that a bitter was a cask beer and if that beer was bottled it was called a pale ale.Hm. I guess those are both strong bitters. Apparently Bass Pale Ale and Whitbread Pale Ale are both "Strong Bitters." It's confusing because they're English Pale Ales, which also happen to be "bitters" (apparently the brewers originally called them "pale ales" and the patrons called them "bitters"). Fullers London Pride and ESB are other examples of bitters.

Honestly, the naming is really confusing...

Edit: Even found this:

https://www.bjcp.org/beer-styles/8c-extra-specialstrong-bitter-english-pale-ale/

Doesn't ring a bell with me. Both bitter beer and pale ale are/can be cask beers. I use the term "beer" to include ales, but not lagers. Just a hangover from the '80's.

I certainly won't argue that point. You are, after all, 100% correct.I'd probably disagree with this here; wheat, either in torrefied or malted form, is very much an acceptable (and IMO desirable) element of a bitter grist, at quantities under 5%, for both head retention and body.

The wider "English bitter" base recipe of specifically British pale malt, specifically British crystal malts (though I would say "up to 7%"), a British yeast and Fuggle/EKG is broadly on the money.

-Edit: speeling

With that said, I cannot say that I've found that torrified wheat really makes much of a difference. I used to use it religiously, but it became a victim of my campaign to rationalize the grains that I keep stocked. I actually wanted to keep it because I believed that it did something, but a couple years of trial and error left me with the disappointing realization that it didn't do much in my brewery. If it's doing good stuff for you, who am I to say it doesn't?

I'd buy into "up to 7%," I'll sometimes do that in the dead of winter when I want a bit more substance in my January and February bitters.

I always keep both malted wheat and torrefied on hand for my hazy IPAs and hefes, so a handful of grammes into a bitter grist doesn't require me stocking things I'd never otherwise use.

I keep meaning to experiment with a small (2-3%) quantity of Golden Naked Oats in a bitter/pale, in lieu of the small amount of wheat I use, to see if they have a desirable effect.

I currently have on tap an English pale that's 7% CaraMalt in lieu of my usual Simpson's T50/Extra Light Crystal and I have to say it's really enjoyable. 88% Warminster floor malted MO, 7% CaraMalt and 5% Torrefied wheat. Hopped with UK Cascade and CF184, my only change for the next batch is going to be a small (ounce or so) keg hop.

I keep meaning to experiment with a small (2-3%) quantity of Golden Naked Oats in a bitter/pale, in lieu of the small amount of wheat I use, to see if they have a desirable effect.

I currently have on tap an English pale that's 7% CaraMalt in lieu of my usual Simpson's T50/Extra Light Crystal and I have to say it's really enjoyable. 88% Warminster floor malted MO, 7% CaraMalt and 5% Torrefied wheat. Hopped with UK Cascade and CF184, my only change for the next batch is going to be a small (ounce or so) keg hop.

Give the Golden Naked Oats a shot. I took them in as my yearly experimental malt a few years ago and I'm still playing with them.I always keep both malted wheat and torrefied on hand for my hazy IPAs and hefes, so a handful of grammes into a bitter grist doesn't require me stocking things I'd never otherwise use.

I keep meaning to experiment with a small (2-3%) quantity of Golden Naked Oats in a bitter/pale, in lieu of the small amount of wheat I use, to see if they have a desirable effect.

I currently have on tap an English pale that's 7% CaraMalt in lieu of my usual Simpson's T50/Extra Light Crystal and I have to say it's really enjoyable. 88% Warminster floor malted MO, 7% CaraMalt and 5% Torrefied wheat. Hopped with UK Cascade and CF184, my only change for the next batch is going to be a small (ounce or so) keg hop.

I gave them a fair shot in my bitters and milds, then moved on. But they're gaining traction in my Northern Brown. I currently think that they add a bit of nuttiness at ~5-10%, but LHBS issues has seen me juggling between Crisp and Warminster over the past two brewing seasons, so I'm not willing to sign on to that belief just yet. I think that may be the case, but I can't say that I know that just yet.

Brewsmith

Home brewing moogerfooger

More reading related to all the above from Brewers Publications

Pale Ale by Terry Foster

https://www.brewerspublications.com...istory-brewing-techniques-recipes-2nd-edition

Mild Ale by David Sutula

https://www.brewerspublications.com...s/mild-ale-history-brewing-techniques-recipes

Like most things in brewing, the answer depends on when in history you want your answer. Naming was much more flexible and only recently have we put more rigid boxes and style guidelines around beers.

Pale Ale by Terry Foster

https://www.brewerspublications.com...istory-brewing-techniques-recipes-2nd-edition

Mild Ale by David Sutula

https://www.brewerspublications.com...s/mild-ale-history-brewing-techniques-recipes

Like most things in brewing, the answer depends on when in history you want your answer. Naming was much more flexible and only recently have we put more rigid boxes and style guidelines around beers.

An Ankoù

Well-Known Member

You re pretty much on the money, here. We don't make a distinction between bitter and strong bitter. A best bitter might be a couple of tenths of a percent abv more than the bitter and, traditionally, cost a penny or two more. All the distinctions that are confusing you are due to your bjpc guidelines. These are totally unknown in the UK and (no offense) we don't want to know as they're a tool for judging competitions in the US, s far as I can see. A bitter from Yorkshire will be entirely different from a bitter from Dorset and we expect local drinks if the same category name to taste different. They're also served differently. Bass and Whitbread both make (used to make) bitter. They're quite different.As far as I can tell, in the UK, all pale ales are "bitters." It also seems to be a terminology difference. Like I mentioned above, originally the breweries called them "pale ales" but the patrons called them "bitters" and you can find both "pale ales" and "bitters" used interchangeably in the names of beers. Apparently this term was created to contrast with "milds" (which is the term used by both the breweries and the patrons).

I personally had thought that bitters were a subset of pale ales, and if you look up all these "bitters" on American beer websites, you'll usually see them listed as "English Pale Ale." So it's actually bitter = pale ale and pale ale = bitter.

Traditionally you'd rarely, if ever find a bottled bitter. When a brewery bottles it's bitter it's sold as pale ale (or so I understand, but I won't insist on it).

Fuller's ESB doesn't actually have the word "bitter" on the label, but it doesn't say "pale ale" either (last time I saw one anyway). I believe that Young's says "bitter" on the bottle, but maybe that's only for export?When a brewery bottles it's bitter it's sold as pale ale (or so I understand, but I won't insist on it).

Last edited:

I've just had a bottle of Timothy Taylor the other day, the darkest "pale" ale i have ever had  .

.

Still, it's written on the label. I'd call it a bitter. The Fuller's is called "Amber" ale... I'd also call that one a bitter.

Still, it's written on the label. I'd call it a bitter. The Fuller's is called "Amber" ale... I'd also call that one a bitter.

An Ankoù

Well-Known Member

Fuller's ESB doesn't actually have the word "bitter" on the label, but it doesn't say "pal ale" either (last time I saw one anyway). I believe that Young's says "bitter" on the bottle, but maybe that's only for export?

I've just had a bottle of Timothy Taylor the other day, the darkest "pale" ale i have ever had.

Still, it's written on the label. I'd call it a bitter. The Fuller's is called "Amber" ale... I'd also call that one a bitter.

I see your point(s) and you're right. My recollections were from the 60s and 70s of an earlier century. "Amber Ale" is a new thing. Fuller's ESB was first touted in 1971 and it certainly wasn't called Amber Ale- this is a modern marketing gimmick. Fullers had Chiswick Bitter at 3.4%, their London Pride at 4.1%, which was their Best Bitter and the ESB really was extra special n the day, being well over-strength for a session beer.

My recollection is that Chiswick was weak and watery, but not unpleasant, Pride was overrated in the same way that Marstons Pedigree was overrated, and ESB was magnificent, but led to a very meandering walk home and a thumping headache the next morning.

In those heady days, beer was beer. It wasn't the strength that mattered, but how many pints you had.

For the record, my favourite was Gales HSB.

And then came Summer Lightning and the world changed.

The good thing is, I can drink them no matter what it's calledI see your point(s) and you're right. My recollections were from the 60s and 70s of an earlier century. "Amber Ale" is a new thing. Fuller's ESB was first touted in 1971 and it certainly wasn't called Amber Ale- this is a modern marketing gimmick. Fullers had Chiswick Bitter at 3.4%, their London Pride at 4.1%, which was their Best Bitter and the ESB really was extra special n the day, being well over-strength for a session beer.

My recollection is that Chiswick was weak and watery, but not unpleasant, Pride was overrated in the same way that Marstons Pedigree was overrated, and ESB was magnificent, but led to a very meandering walk home and a thumping headache the next morning.

In those heady days, beer was beer. It wasn't the strength that mattered, but how many pints you had.

For the record, my favourite was Gales HSB.

And then came Summer Lightning and the world changed.

Regarding Fuller's amber, that's waaaayyyyy better from tap. Also different strength from tap. I don't like the bottled version that much but the tap version is magnificent.

Similar threads

- Replies

- 6

- Views

- 302

- Replies

- 30

- Views

- 2K