Translation courtesy of google if it helps " muddy " the water

But this seems to summarise it well from Braukaiser

"

In

Abriss der Bierbrauerei, German brewing author Ludwig Narziss defines

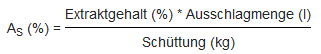

Sudhausausbeute (German for brewhouse efficiency) as the ratio between the amount of extract in the boil kettle and the amount of grain that was used [Narziss, 2005]:

Sudhausausbeute = (kettle volume in l * kettle extract in % * kettle specific gravity) / grain mass in kg

Note that this is a different approach for defining efficiency. The reference is not the laboratory extract of the grain, but the total weight of the grain. The latter includes the weight of the husks and other insoluble material. Because of that the the

Sudhausausbeute is also affected by the potential (or laboratory extract) of the malt used. This is also the definition that German home brewers use for efficiency. Thus care needs to be taken when reading efficiency numbers from German sources. While 75% is a very good efficiency number when based on the total grain weight (most grains laboratory extract is about 80% of their weight) it is only a modest efficiency when seen as based on the laboratory extract of the grain."

Sudhausausbeute

The

brewhouse yield is a measure of the effectiveness of the work in the

brewhouse . It describes what proportion of the

malt went into solution during

mashing . All work steps in the brewhouse are included, from

crushing to

beating the

wort after

hop boiling but before

hot break separation .

The extract content and the volume of the cast-out

wort are required as measured values . The

extract content is measured using a

saccharometer (

areometer ,

beer spindle ) at its calibration temperature in °P (degrees Plato, corresponds to % vol ). The wort may have to be cooled. The volume of the

wort is either read off the scale on the calibrated

wort kettle or determined using a calibrated measuring rod.

ATTENTION: The calculation of the brewing yield, which is also called the hot wort yield, should be calculated using the hot wort volume (including the hot trub ) , not the cast-out volume 1) .

The

brewhouse yield A S is calculated as follows

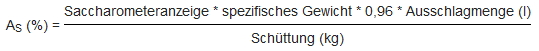

This calculation is not accurate for various reasons. The volume of the wort is determined at almost boiling temperature, but the measuring devices are usually calibrated to 20°C. The cooking pan, on the other hand, expands at high temperatures. Substances were also introduced into the wort from the hops, which falsify the value of the wort quantity. A correction value of 4% is assumed for all of these factors, and the deflection quantity is therefore multiplied by 0.96.

The value read on the saccharometer indicates the percentage by weight of the extract. These must be converted to percentages by volume by multiplying them by the

specific gravity of the

wort .

This gives the following corrected formula for the brewhouse yield:

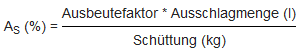

The

specific weight SG can be roughly calculated (see article

SG ) or read more precisely from the

Plato table . The product of the saccharometer display, specific gravity and expansion correction factor is also summarized there as a

yield factor, so that the formula can be simplified again with the help of the

Plato table :

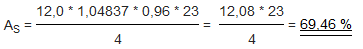

Example:

23.0 l of wort with 12.0% original wort were produced from a bed of 4 kg of malt. The

brewhouse yield is thus

The values for the

specific gravity (1.04837) or the

yield factor (12.08) can be read from the

Plato table for the extract content of 12.0% wt (saccharometer reading).

The value of the

brewhouse yield in modern breweries is well over 75%. Depending on

the mashing process and malt quality, around 65 to 75% is expected in the home brewing sector.

Other values used to assess the effectiveness of the brewing process are the cold wort yield, the fermenting room yield

and the

overall yield .

Links

1) Brew Recipe Developer Dokumentation DE

I have to say I know where I stand with the definitions used by brewfather summarised by

@doug293cz rather than the above.

![Craft A Brew - Safale S-04 Dry Yeast - Fermentis - English Ale Dry Yeast - For English and American Ales and Hard Apple Ciders - Ingredients for Home Brewing - Beer Making Supplies - [1 Pack]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/41fVGNh6JfL._SL500_.jpg)