I made valiant attempt to put this thread back on track, and discuss mash temp results, but folk seem to be obsessing over brulosphy.

From my point of view, we have a guy (Brulosphy) who goes to pretty extreme lengths to compare the same beer made with, what many exponents would consider, siginficant brewing changes. Its fun to read, its interesting. For me, and I suggest some others, it can be quite eye opening. In many instances the expected differences in the same beer are not all that clear cut. In others they are. For some, its not his brewing process that's in question rather, how he does his triangle testing with tasters. The explantion of which is frankly rather boring by comparison.

Until someone actually goes to the lengths Brulosphy does to compare similar grain bills, then its just one source for any sort of evidence (anecdotal as it may well be) for and against some of the long held truths about the hobby.

Can those who argue his method provide any evidence against his experimental resutls from personal experience? I am honestly intrigued to find out. For example, do beers mashed at different temps ( say 2 degrees or even 8-10 degrees) really taste different?

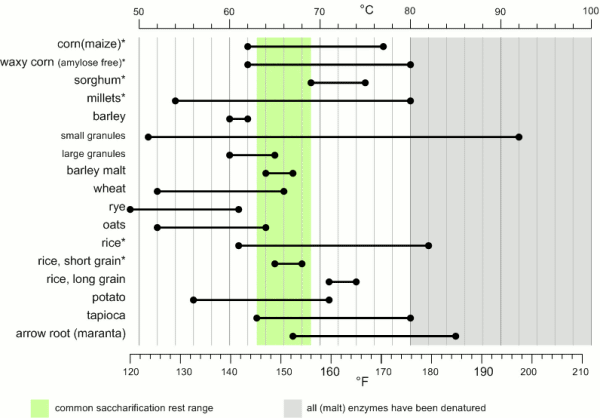

Getting back to the thread theme, my anecdotal evidence suggests that by mashing in reverse, from 158 degrees, back down to around 145-148, i am getting a highly fermentable wort. Popular belief would maintain i have long denatured my beta amylase, and get a less fermentable wort. This does not happen. I should add, that i do my mash like this because I am simply lazy, and dont want to attend to it in order to maintain steady temps.

Point is, until someone actually goes and tests a longheld brewing tradition, or theory, like Brulosphy guy does, then they might be just that.

![Craft A Brew - Safale S-04 Dry Yeast - Fermentis - English Ale Dry Yeast - For English and American Ales and Hard Apple Ciders - Ingredients for Home Brewing - Beer Making Supplies - [1 Pack]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/41fVGNh6JfL._SL500_.jpg)