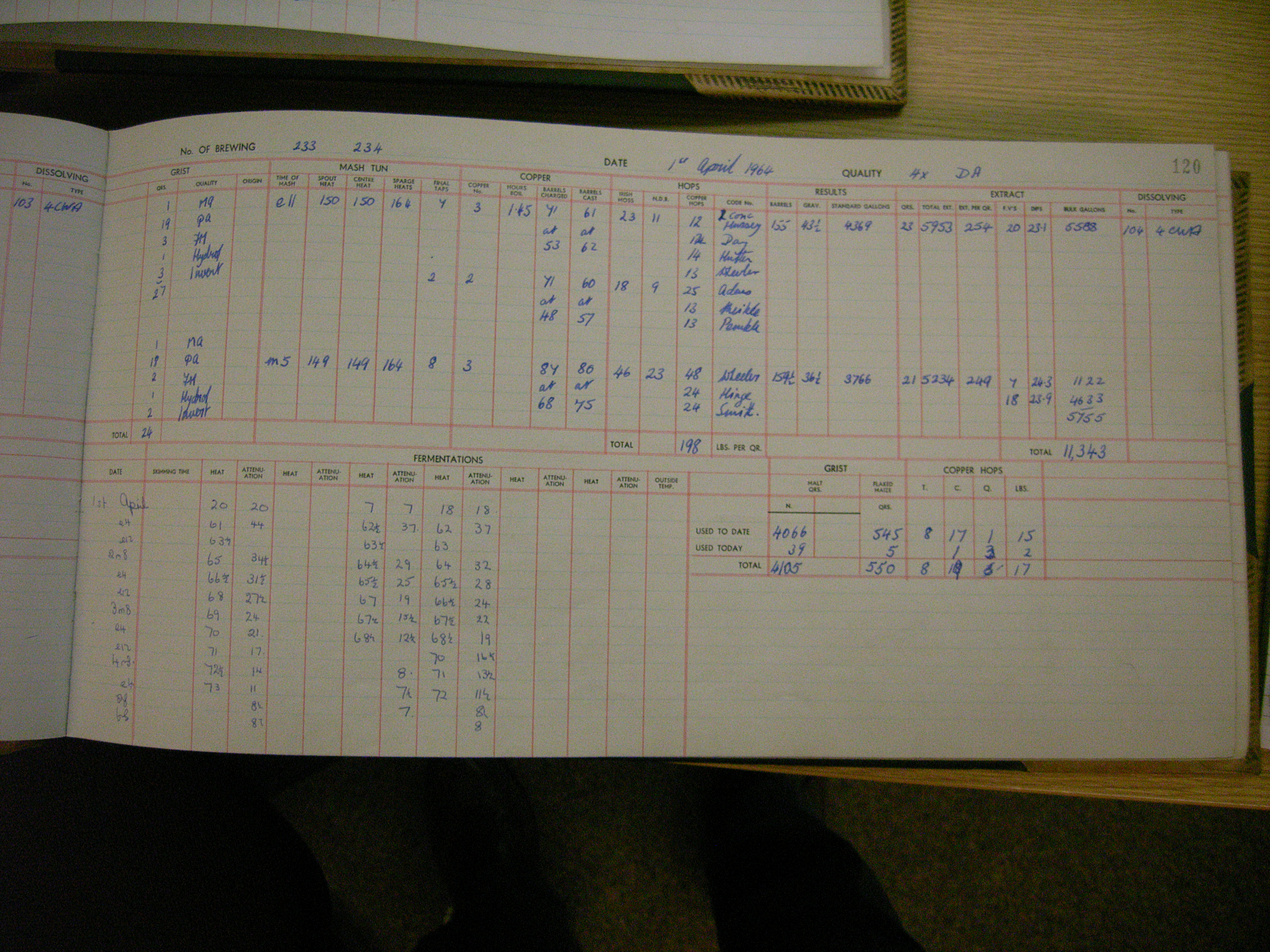

My stock includes inverts #1, #2 and #3 made by the only remaining brewing sugar manufacturer in Britain,

Ragus. It is my opinion that we cannot accurately replicate their product without a vast amount of work and some specialized equipment, but that we can produce something similar enough to enhance our beers enough to warrant the small necessary cost and effort.

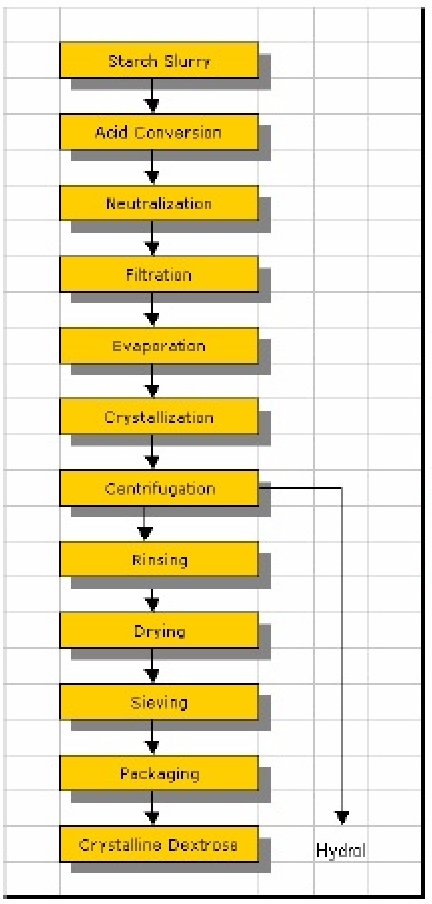

Invert sugar is glucose and fructose in combination. Sucrose can be converted to invert by various methods, but a combination of heat and acid is the quickest, and the method used by Ragus, described in the earlier link. In basic terms, the higher the temperature and/or the lower the pH of a sucrose solution, the quicker inversion happens. Once inversion has completed by this method, it is necessary to slow/stop it by reducing temperature and/or raising pH, else the fructose and sucrose so produced will be modified to other substances. Ragus heat their sucrose (refined cane sugar) solution to 70C, when all sugar goes into solution, suggesting the ratio by weight will be, two parts sucrose to one part water. This temperature is then maintained, when acid is added to pH 1.6 and the mixture is stirred continuously. Samples are taken and measured in a polarimeter until refracted light reaches minus 20 degrees (why it is called inverted sugar). A base is then added to increase pH and substantially slow/stop the process.

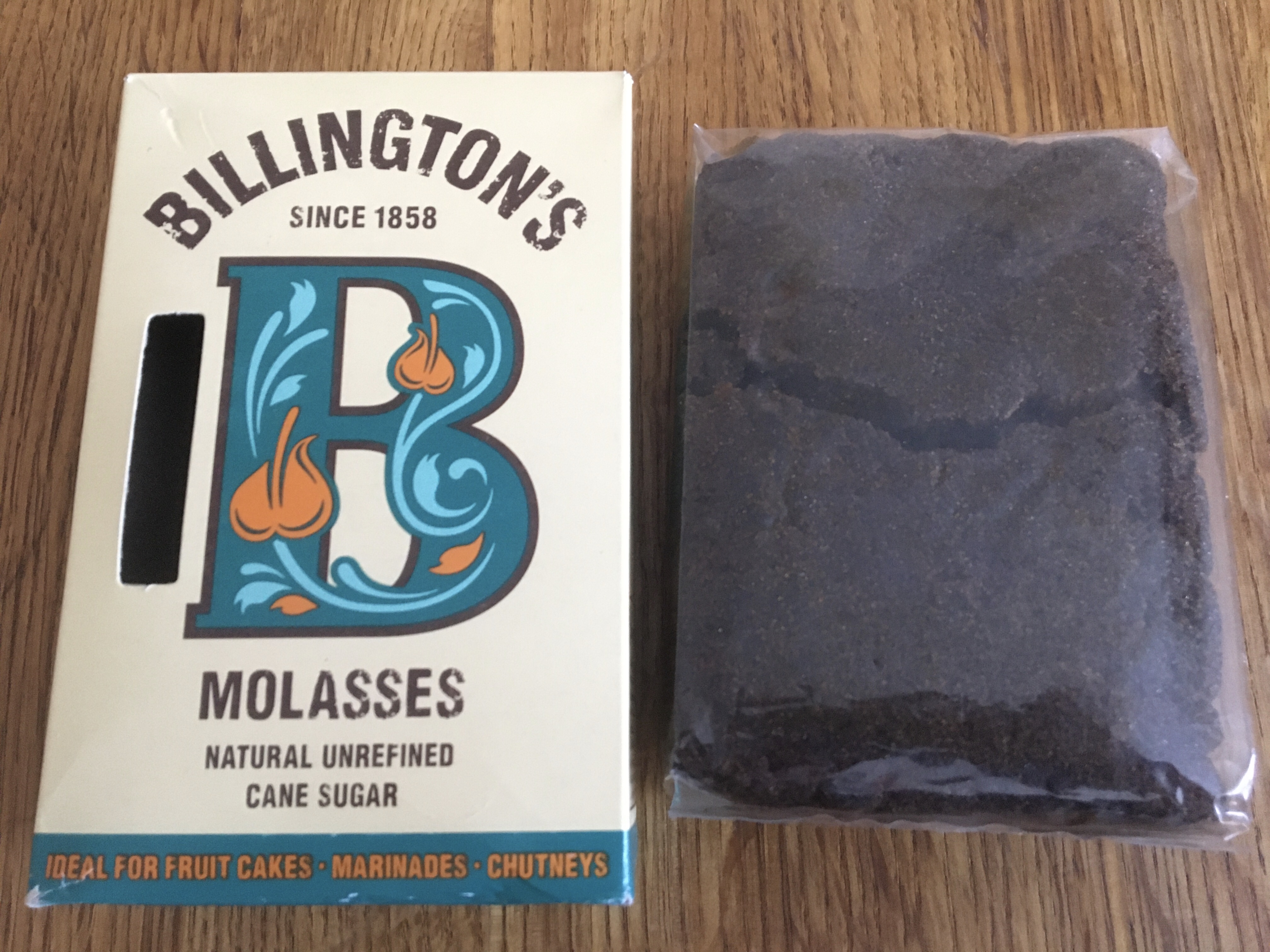

A molecule of sucrose releases one of water when inverted, and sugar can be dissolved in newly converted invert. Ragus do this to create their different grades of brewing sugars. #1 will have added raw cane sugar, #2 some with more unrefined product while #3 will likely have almost pure molasses addition and this is when most American made inverts diverge from British.

I frequently read American advice to increase temperature to produce a darker invert sugar, which it does, but, it does by caramelizing inverted sugars rather than adding other flavors. In Britain if we want to darken a beer and add caramel flavors, we add Brewers Caramel.

View attachment 758076

I found it very difficult to hold a sugar solution at 70C and when I tried pH 1.6 while simmering, the converted sugars quickly degraded. Now I add enough acid when the sugar dissolves that would achieve pH 2.0. I then simmer for up to 5 minutes when the solution changes from clear to a soft/light yellow. At that point more sugar is added (5%) and mixed in before the heat is removed and a small amount of sodium bicarbonate is added. For #1 a light brown or white sugar, #2 a dark brown sugar and for #3 molasses or blackstrap or Black Treacle. A near heaped spoon of citric acid crystals will produce pH 2.0 in a mixture of a kg of cane sugar and 500 ml of low alkalinity water.

![Craft A Brew - Safale BE-256 Yeast - Fermentis - Belgian Ale Dry Yeast - For Belgian & Strong Ales - Ingredients for Home Brewing - Beer Making Supplies - [3 Pack]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/51bcKEwQmWL._SL500_.jpg)