landoa

WheatBeer

- Joined

- Jan 22, 2021

- Messages

- 47

- Reaction score

- 21

Hello,

Just thinking about how to save time during the mash. Some folks do an overnight mash in a mash tun. I have a steel kettle and i'm sure i'd lose too much heat. If the temperature falls below 130F, there problems with bacteria which can be killed off during the boil, but may leave a persistent off taste.

My compromise would be to start the mash first thing in the morning around 8h00 and come back around 11h00 after morning errands. The normal 60-90 minute mash would be 3 hours. Maybe this will bump up efficiency a little but it would save time as I wouldn't be stuck at home.

I would do it with BIAB, which apparently requires more stirring more often during the mash. I figure the longer mash would make up for less stirring.

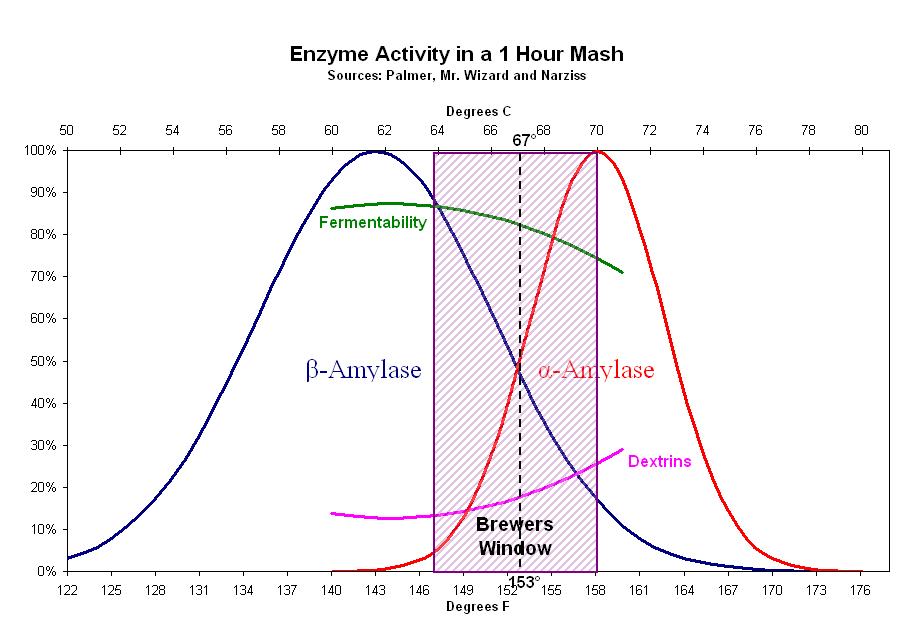

I lose around 5F / hour. So, if I started at 153F, i'd end up at around 138F.

Sounds doable?

Just thinking about how to save time during the mash. Some folks do an overnight mash in a mash tun. I have a steel kettle and i'm sure i'd lose too much heat. If the temperature falls below 130F, there problems with bacteria which can be killed off during the boil, but may leave a persistent off taste.

My compromise would be to start the mash first thing in the morning around 8h00 and come back around 11h00 after morning errands. The normal 60-90 minute mash would be 3 hours. Maybe this will bump up efficiency a little but it would save time as I wouldn't be stuck at home.

I would do it with BIAB, which apparently requires more stirring more often during the mash. I figure the longer mash would make up for less stirring.

I lose around 5F / hour. So, if I started at 153F, i'd end up at around 138F.

Sounds doable?

![Craft A Brew - Safale BE-256 Yeast - Fermentis - Belgian Ale Dry Yeast - For Belgian & Strong Ales - Ingredients for Home Brewing - Beer Making Supplies - [3 Pack]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/51bcKEwQmWL._SL500_.jpg)