Phillip Taud

Member

- Joined

- Jan 4, 2019

- Messages

- 14

- Reaction score

- 1

Hi there,

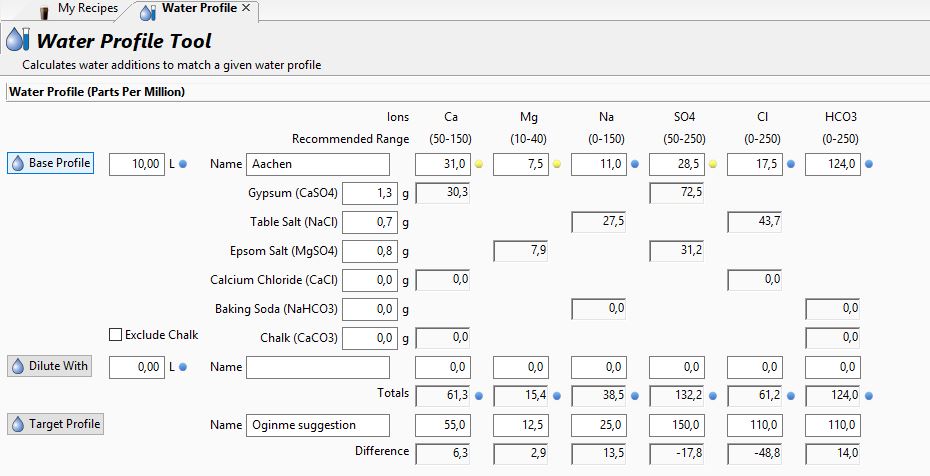

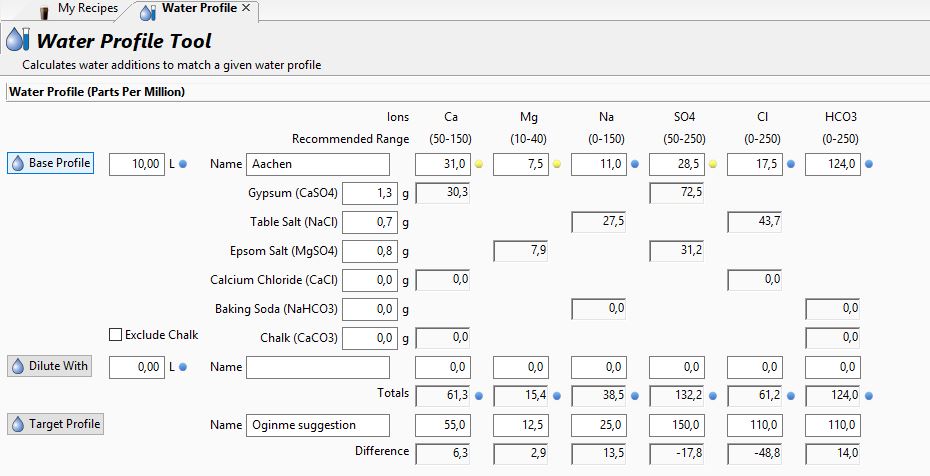

I am here in Germany trying to brew crisp, dry Pale Ales / IPAs and fresh american Lagers. So far I have been aiming for these water targets. What are your thoughts and am I doing the right thing? My beers definitely could be dryer. My pre-mash pH is also usually a little high at 5,9 which I have not adjusted so far.

Suggestions would be great!

Thx, Phillip

I am here in Germany trying to brew crisp, dry Pale Ales / IPAs and fresh american Lagers. So far I have been aiming for these water targets. What are your thoughts and am I doing the right thing? My beers definitely could be dryer. My pre-mash pH is also usually a little high at 5,9 which I have not adjusted so far.

Suggestions would be great!

Thx, Phillip

![Craft A Brew - Safale S-04 Dry Yeast - Fermentis - English Ale Dry Yeast - For English and American Ales and Hard Apple Ciders - Ingredients for Home Brewing - Beer Making Supplies - [1 Pack]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/41fVGNh6JfL._SL500_.jpg)