You may have noticed by now, that beer is over 90% water, so saying that brewing water is important is an understatement of galactic proportions. There are many books on the subject, but they are so in-depth usually that most home brewers either lose interest or mental capacity in the attempt. So, I searched and searched and saw that there is a site or two that does discuss generalized water profiles, but not a “catch all” type of formula. There is a good reason for this…

All pro-brewers will tell you that each recipe should have its own water profile, each construction of malt, hops and yeast needs its profile fine-tuned to be perfect. This is seriously hard to get your head around in the beginning, I do understand, but ,similarly, you need to realize that while I am going to be giving water profiles for many styles, they may never be optimal for your particular recipe, so keep playing with it until you get it right – it takes on average 2 or 3 brews of the same recipe with different profiles to get it right in a commercial setup where we know our stuff – home brewers may take longer, but don’t get disheartened.

The plus side is that you will get your beers to the level where they don’t taste like homebrew anymore and will taste like commercial examples of the style – this is the final frontier after you have mastered the rest, including yeast control. You will most likely be shocked at the quality of even your first attempts.

One last note would be that this is a beginner guide to brewing water, I have left out much information, but it is by design… I don’t want newbie’s to get put off and I don’t want to get stuck writing a thesis either.

So, I’ve come up with the following analogy to explain this –

Say you have a beautiful painting of a ship on the sea, lots of beautiful blue hues, brown and beige from the ship and oranges and pinks from the sunset in the sky. Pretty with all its masterful brushstrokes and swirl techniques…this is your beer’s flavor in all its perfection, with all the right highlights and hues and a perfect arrangement of water chemistry.

Now, you take a pair of those John Lennon-type round glasses with bright red lenses and – for dramatic effect – you take a stick of butter and rub them on the lenses. Now you put these on and you look at the aforementioned painting. All the colors are wrong, the artwork distorted and bent beyond recognition and you actually can’t make out what it originally was. The muddy lenses won’t allow you to see the beauty for what it actually is. This is the same beer recipe with the wrong water chemistry – and yes the results are just as dramatic between the two. Don’t believe me? Take an imperial stout water recipe and try to brew a pilsner with it – you’ll end up drinking a pale beer with the mineral profile of a granite quarry.

What are you doing? When you balance your water chemistry vs your recipe, you are performing a similar function of a sound engineer at a sound board. The sound engineer shifts the hundreds of keys, ensuring each note is either amplified or muted so that the overall composition is a marvelous piece of art – the difference between a platinum selling artist and your pot-head buddy in his garage!

This is the bit about the different elements in brewing water – I’m going to keep this as simple as absolutely possible.

Calcium – 50 to 200ppm (Added generally through Gypsum or Calcium chloride). This is the most important item on the list. This element is responsible for actually lowering mash pH in the first place. It’s also crucial for yeast health and a clear beer. The higher the amount, the more easily the yeast flocculates. It is also essential for enzymatic processes in the mash.

Magnesium – 0 to 30ppm (Added through Magnesium Sulphate). This is another element that is one of the primary contributors to lowering mash pH, although not as well as calcium. It is also a yeast nutrient. The minimum amount is zero in the mash water because all barley wort contains loads of this stuff, but I can tell you from experience that adding even a small amount of magnesium (in the form of Epsom salts or MgSO4) to your mash does great things for the flavor of your beer.

Sulphate – 50 to 400ppm (Added through Gypsum or Magnesium Sulphate). The first major flavor component, many brewing software types will tell you this increases “bitter” in a beer, but it’s a little more complicated than that. It’s a combination of either sharpness, bitterness or dryness in the flavor perception, as well as increasing the hop character in beers. The only time I would go over the 250ppm limit is if I’m looking to do a “to style” Dortmund export or something similar. You’d be forgiven for thinking an IPA needs more, but it doesn’t, as it is one of the contributing factors to an IPA’s bitterness sticking to your tongue. Most award winning IPA’s have a flash of skull-rattling bitterness and a clean hoppy finish that encourages you to drink more = less than 200ppm. If it lingers on the tongue too long, you’ll lose on drinkability. Another point to ponder, is that despite it saying that the minimum requirement is 50ppm, I forget it altogether if I’m brewing continental pilsners and other similar lagers, due to the fragile flavor profile of those beer styles and the hops implemented.

Chloride – 0 to 200ppm (Added through Calcium Chloride or Salt). This is the other major flavor component – it provides a fuller, rounder or sweeter perception to the beer, and is used to either increase malt flavor perception or to temper the effects or sulphates (known as the sulphate to chloride ratio, which we will discuss shortly). There are brewers who take the levels of chlorides up to 300ppm or more, but I would not for various well-informed reasons, so I recommend you don’t either. It’s a very important element for malt forward beer styles.

Sodium – 0 to 150ppm (Added through Salt or Bicarbonate of Soda) Sodium, sodium, sodium – what to do with you? Sodium is an element that is sometimes unavoidable when correcting water chemistry and can lend a sweet quality to certain beers, but can become salty when you approach or exceed 150ppm. It does lend a certain well rounded character to pale beers as well, but much better to keep the concentrations lower than 100ppm unless you are absolutely sure of what you’re doing.

Bicarbonate – 0 to 250ppm (Added through Bicarbonate of Soda, usually) This is the primary ingredient that stands between your stout being wonderfully chocolatey and rich and a one-dimensional cold espresso disappointment. When you need an alkalinity buffer, this is your go-to addition. It does make hops overly bitter in a harsh sort of way, so avoid it completely in highly hopped beers as well as pale beers (it can taste harsh on its own too in beers below 7 SRM).

This is the ratio between the two major flavor ions we discussed earlier. To keep matters simple, suffice it to say that you actually really need at least 50ppm of either for a noticeable difference and never max out both values as it will cause a minerally taste in your beer (super strong beers can handle this, but most won’t). The subject of whether to make a beer sulphite forward, chloride forward or balanced is highly dependent on what kind of beer you’re trying to make. If hops play a starring role, go for sulphites. If it’s malt, go for chlorides. If both hops and malt are to be highlighted a balanced profile is preferred. It’s the level of the ratio that makes all the difference in which aspect is going to shine, but remember that adding, for example sulphur, won’t just highlight hops, but also make the beer seem drier. It’s one of those things you have to play with to get it right. When I wasn’t sure - back when I started asking these questions - I simply added small amounts of a solution of either gypsum and water or calcium chloride and water to a glass of beer to figure out which way to go the next time I brewed the same recipe.

To illustrate the difference between the two, let’s look at 2 different recipes for the same beer style and figure out which way to go. I usually use a beer like cream ale for examples, as it’s an easy beer to make and can be interpreted many different ways:

Recipe 1: Cream ale with corn meal

• 80% 2 row malt

• 20% corn meal or flaked corn

• 20 IBU hops (dry hopped as well)

• 64.4°C mash temp

With the above recipe, I have the fact that the corn will lend an element of sweetness, but I want this to be a cream ale that has a definite hop character. I have to drop to the mash temp and make this beer sulphite-dominant to make sure I end up with that fresh hop character and typical crisp finish required of cream ales. Sulphite/chloride ratio of about 1.5 (slightly bitter)

Recipe 2: Cream ale with rice and sugar

• 80% 2 row malt

• 15% rice flakes

• 5% sugar

• 15 IBU hops (bittering only)

• 66°C mash temp

This recipe, on the other hand, is already going to be very dry and crisp due to the sugar and the rice. In this case I might opt to increase the mash temperature and to make the beer a malty chloride-dominant brew. Sulphite/chloride ratio of about 0.6 (very malty)

As you can see, there is no one-rule-fits-all scenario. You have to think about what you want to create and there are no wrong answers as long as the beer tastes good when you’re done.

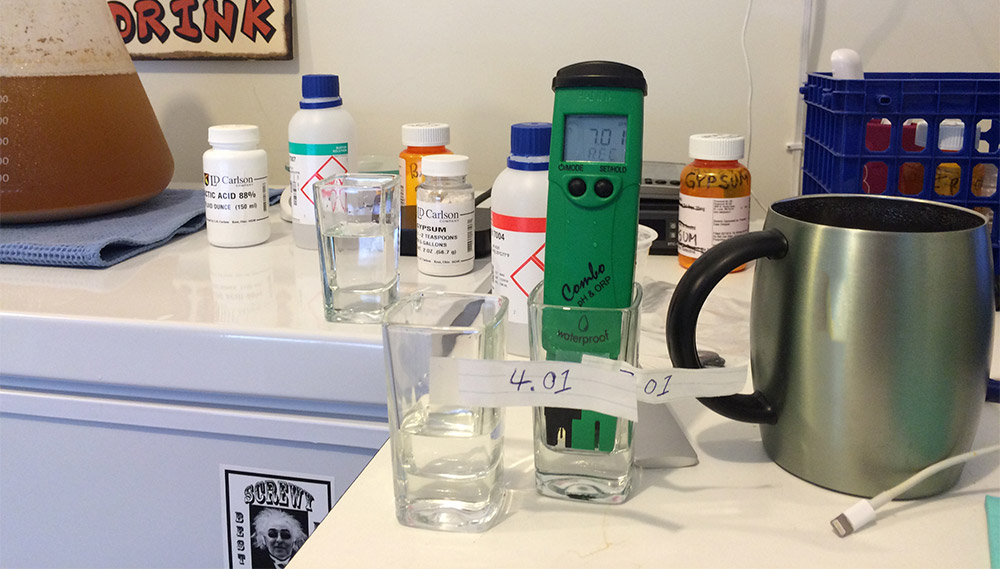

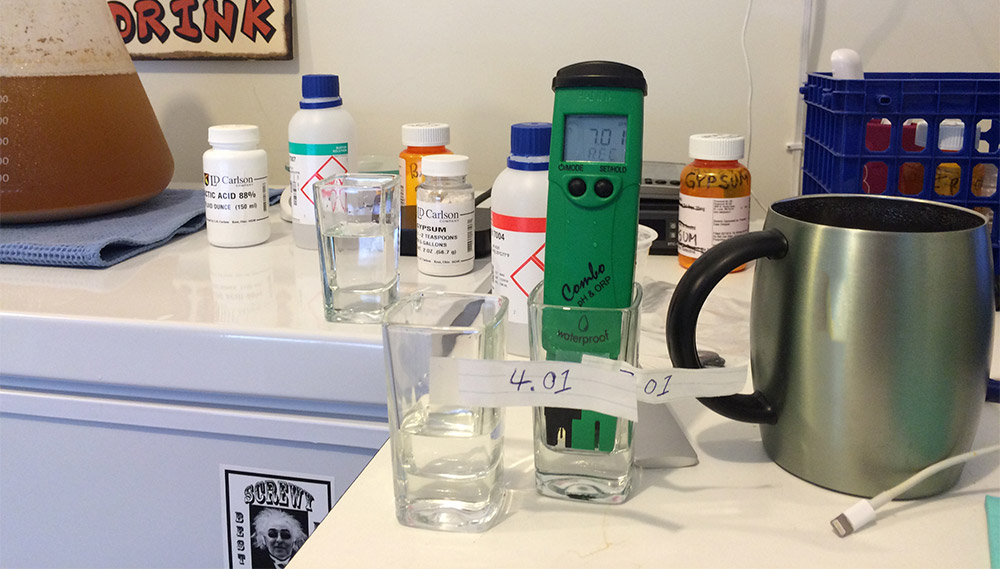

Dropping the mash pH is as simple as either increasing the calcium content, or actually adding acid to it for paler styles. For the purposes of beginners (and this article) I would ask that you do 2 things:

1. Stick to the amount of calcium in the recipes / formulas given for now.

2. BUY A (%#!@!) PH METER!!!...and measure your mash pH 10 minutes after doughing in.

ONLY add acid if absolutely required.

3. When it comes to using acid, try using orthophosphoric acid if you can get hold of it. Lactic acid if you can’t.

4. Buy another pH meter – you can’t work without these things.

PRO TIP: Only pale and amber beers benefit from a pH of 5.2 to 5.4. To get your brown ales and stouts to have that rich flavor, aim for a mash pH of around 5.6 to 5.8. Along with residual sugars, it’ll help the final beer pH finish higher, softening that roast element into something luxurious and wonderful.

I have opted to use the 2008 BJCP guidelines, as they are more familiar to most than the new 2015 version. Coupled with that, Jamil Zainasheff’s book “20 Classic Styles” can be used along with the following guidelines. If you brew it and it doesn’t come out the way he describes in the book, the water chemistry is wrong and you should try again. Also, dodging the subject of alkalinity and residual alkalinity like a plague, I have expressed alkalinity as a value of bicarbonates, easily added to soft or RO water through the addition of sodium bicarbonate (baking soda). If you have water that exceeds this amount for the style you are trying to make, ditch it for a few bottles of RO or distilled water and either dilute or build from scratch. This will however bring up the subject of sodium – if so and in doubt, just try to aim for a sodium level below 100ppm unless stated otherwise.

A note on calculations and water additions:

• I am assuming you are using software to calculate your water – no one in their right mind would start off trying to manually calculate water chemistry. For this simplified version, I have opted to use BeerSmith 2 water profile calculator.

• Due to the low volume of the water homebrewers use and the fact that brewing water chemistry generally uses the same sorts of compounds, you are going to be scraping around so many small amounts of powders, it would make even the most hardened cocaine addict squirm. If you are struggling with getting the measurements right, increase the volume of water you are treating to make it both easier and more accurate – it is far easier to treat 50 gallons of water than it is to treat 5.

• Always look at the ABV and color range of your intended brew, if it’s on the higher side of the style, aim for the higher mineral content specified below, if it’s lower, aim lower.

• On many forums I have seen people arguing over the amount of residual minerals actually going into the beer and enhancing the flavor, due to boil off, mash absorption, etc, etc.

One golden rule: Less minerals is always better. When you calculate, calculate for the batch size alone i.e. you want to make 5 gallons, so you calculate on 5 gallons of water alone and never mind about the sparge. The reason is that when you boil, you concentrate everything. I’d rather you learn to err on the side of caution and get the hang of it first, instead of overdoing it and being unhappy with your result. You beer will taste great, I promise!

Let’s work through a few examples to help you to use these water profile recipes.

So I want to make a beer with, say, 70 IBU’s of bitterness, about 6 to 7% abv and the color is roughly amber. The alcohol content, firstly, and the color, secondly, ensure that I can aim for the high side of the IPA spectrum.

*These are recommended norms, but I would omit them entirely for this style.

My Preferred Additions for 5 Gallon (19 liter) Batch:

• 5g Calcium Sulphate (Gypsum)

• 1g Magnesium Sulphate (Epsom Salts)

• 2g Calcium Chloride

This water profile makes sure all bases are covered for an American IPA.

So you have water that’s not ideal for a Munich Helles…what now? Let’s have a look. Remember that everyone's tap water is different, so you will need to add your own numbers for your tap water.

First thing to do, due to the bicarbonates, it to dilute the tap water with reverse osmosis water 40% (RO) to 60% (Tap) - that will get us to:

My preferred additions after dilution for 5 gallon (19 liter) batch:

• 4g Calcium Chloride

This water will complement a Munich Helles quite nicely – the little bit of sodium still in the water will barely be noticeable, if anything will give it just a hint of sweetness.

Use store bought water if your tap water is too far gone.

Use store bought water if your tap water is too far gone.

You’re sitting with water that’s more suited to a strong stout than anything else.

Step 1: Dump the bucket of tap water on the lawn

Step 2: Go to the shop and buy reverse osmosis water

Step 3: Continue as in first example.

I’m sure you get the general idea by now. If not, feel free to post in the comments section and I’ll help you out with a few more. Highly recommended further reading:

WATER: A comprehensive guide for brewers (John Palmer & Colin Kaminski)

I hope these formulas assists all those yet to take the plunge into the final frontier in the quest for the perfect pint. This really is the last step in perfection and is absolutely essential to those wishing to go commercial. I wish you the best of luck…

*These are recommended norms, but I would omit them entirely for this style

*These are recommended norms, but I would keep them on the low side for this style

16E. Belgian Specialty Ale: No recommendation as it is too varied. Look at your recipe, note the colour and alcohol level and pair it to a beer you think is the most similar – then use that beer’s water profile.

*Minerals don’t have a huge impact on sour beers, due to all the bugs we add in there. Your concentration should be on enough calcium to get your mash Ph down and that’s about it. If you are still not sure, generally aim for the lower end of the spectrums provided.

Aim for the lower end of the spectrum.

Look at the base style of the beer and use the guidelines associated with that beer.

Look at the base style of the beer and use the guidelines associated with that beer.

All other beers in this category need to be assessed by their base beer style.

Have a look at the beer you are trying to create. Match the colour, bitterness, alcohol content to another beer on the styles list. Use the one you think fits closest to that style.

All pro-brewers will tell you that each recipe should have its own water profile, each construction of malt, hops and yeast needs its profile fine-tuned to be perfect. This is seriously hard to get your head around in the beginning, I do understand, but ,similarly, you need to realize that while I am going to be giving water profiles for many styles, they may never be optimal for your particular recipe, so keep playing with it until you get it right – it takes on average 2 or 3 brews of the same recipe with different profiles to get it right in a commercial setup where we know our stuff – home brewers may take longer, but don’t get disheartened.

The plus side is that you will get your beers to the level where they don’t taste like homebrew anymore and will taste like commercial examples of the style – this is the final frontier after you have mastered the rest, including yeast control. You will most likely be shocked at the quality of even your first attempts.

One last note would be that this is a beginner guide to brewing water, I have left out much information, but it is by design… I don’t want newbie’s to get put off and I don’t want to get stuck writing a thesis either.

What is the Importance of Brewing Water Anyway?

So, I’ve come up with the following analogy to explain this –

Say you have a beautiful painting of a ship on the sea, lots of beautiful blue hues, brown and beige from the ship and oranges and pinks from the sunset in the sky. Pretty with all its masterful brushstrokes and swirl techniques…this is your beer’s flavor in all its perfection, with all the right highlights and hues and a perfect arrangement of water chemistry.

Now, you take a pair of those John Lennon-type round glasses with bright red lenses and – for dramatic effect – you take a stick of butter and rub them on the lenses. Now you put these on and you look at the aforementioned painting. All the colors are wrong, the artwork distorted and bent beyond recognition and you actually can’t make out what it originally was. The muddy lenses won’t allow you to see the beauty for what it actually is. This is the same beer recipe with the wrong water chemistry – and yes the results are just as dramatic between the two. Don’t believe me? Take an imperial stout water recipe and try to brew a pilsner with it – you’ll end up drinking a pale beer with the mineral profile of a granite quarry.

What are you doing? When you balance your water chemistry vs your recipe, you are performing a similar function of a sound engineer at a sound board. The sound engineer shifts the hundreds of keys, ensuring each note is either amplified or muted so that the overall composition is a marvelous piece of art – the difference between a platinum selling artist and your pot-head buddy in his garage!

The Aspects to Consider in Water Chemistry

This is the bit about the different elements in brewing water – I’m going to keep this as simple as absolutely possible.

Calcium – 50 to 200ppm (Added generally through Gypsum or Calcium chloride). This is the most important item on the list. This element is responsible for actually lowering mash pH in the first place. It’s also crucial for yeast health and a clear beer. The higher the amount, the more easily the yeast flocculates. It is also essential for enzymatic processes in the mash.

Magnesium – 0 to 30ppm (Added through Magnesium Sulphate). This is another element that is one of the primary contributors to lowering mash pH, although not as well as calcium. It is also a yeast nutrient. The minimum amount is zero in the mash water because all barley wort contains loads of this stuff, but I can tell you from experience that adding even a small amount of magnesium (in the form of Epsom salts or MgSO4) to your mash does great things for the flavor of your beer.

Sulphate – 50 to 400ppm (Added through Gypsum or Magnesium Sulphate). The first major flavor component, many brewing software types will tell you this increases “bitter” in a beer, but it’s a little more complicated than that. It’s a combination of either sharpness, bitterness or dryness in the flavor perception, as well as increasing the hop character in beers. The only time I would go over the 250ppm limit is if I’m looking to do a “to style” Dortmund export or something similar. You’d be forgiven for thinking an IPA needs more, but it doesn’t, as it is one of the contributing factors to an IPA’s bitterness sticking to your tongue. Most award winning IPA’s have a flash of skull-rattling bitterness and a clean hoppy finish that encourages you to drink more = less than 200ppm. If it lingers on the tongue too long, you’ll lose on drinkability. Another point to ponder, is that despite it saying that the minimum requirement is 50ppm, I forget it altogether if I’m brewing continental pilsners and other similar lagers, due to the fragile flavor profile of those beer styles and the hops implemented.

Chloride – 0 to 200ppm (Added through Calcium Chloride or Salt). This is the other major flavor component – it provides a fuller, rounder or sweeter perception to the beer, and is used to either increase malt flavor perception or to temper the effects or sulphates (known as the sulphate to chloride ratio, which we will discuss shortly). There are brewers who take the levels of chlorides up to 300ppm or more, but I would not for various well-informed reasons, so I recommend you don’t either. It’s a very important element for malt forward beer styles.

Sodium – 0 to 150ppm (Added through Salt or Bicarbonate of Soda) Sodium, sodium, sodium – what to do with you? Sodium is an element that is sometimes unavoidable when correcting water chemistry and can lend a sweet quality to certain beers, but can become salty when you approach or exceed 150ppm. It does lend a certain well rounded character to pale beers as well, but much better to keep the concentrations lower than 100ppm unless you are absolutely sure of what you’re doing.

Bicarbonate – 0 to 250ppm (Added through Bicarbonate of Soda, usually) This is the primary ingredient that stands between your stout being wonderfully chocolatey and rich and a one-dimensional cold espresso disappointment. When you need an alkalinity buffer, this is your go-to addition. It does make hops overly bitter in a harsh sort of way, so avoid it completely in highly hopped beers as well as pale beers (it can taste harsh on its own too in beers below 7 SRM).

Sulphate to Chloride Ratio

This is the ratio between the two major flavor ions we discussed earlier. To keep matters simple, suffice it to say that you actually really need at least 50ppm of either for a noticeable difference and never max out both values as it will cause a minerally taste in your beer (super strong beers can handle this, but most won’t). The subject of whether to make a beer sulphite forward, chloride forward or balanced is highly dependent on what kind of beer you’re trying to make. If hops play a starring role, go for sulphites. If it’s malt, go for chlorides. If both hops and malt are to be highlighted a balanced profile is preferred. It’s the level of the ratio that makes all the difference in which aspect is going to shine, but remember that adding, for example sulphur, won’t just highlight hops, but also make the beer seem drier. It’s one of those things you have to play with to get it right. When I wasn’t sure - back when I started asking these questions - I simply added small amounts of a solution of either gypsum and water or calcium chloride and water to a glass of beer to figure out which way to go the next time I brewed the same recipe.

To illustrate the difference between the two, let’s look at 2 different recipes for the same beer style and figure out which way to go. I usually use a beer like cream ale for examples, as it’s an easy beer to make and can be interpreted many different ways:

Recipe 1: Cream ale with corn meal

• 80% 2 row malt

• 20% corn meal or flaked corn

• 20 IBU hops (dry hopped as well)

• 64.4°C mash temp

With the above recipe, I have the fact that the corn will lend an element of sweetness, but I want this to be a cream ale that has a definite hop character. I have to drop to the mash temp and make this beer sulphite-dominant to make sure I end up with that fresh hop character and typical crisp finish required of cream ales. Sulphite/chloride ratio of about 1.5 (slightly bitter)

Recipe 2: Cream ale with rice and sugar

• 80% 2 row malt

• 15% rice flakes

• 5% sugar

• 15 IBU hops (bittering only)

• 66°C mash temp

This recipe, on the other hand, is already going to be very dry and crisp due to the sugar and the rice. In this case I might opt to increase the mash temperature and to make the beer a malty chloride-dominant brew. Sulphite/chloride ratio of about 0.6 (very malty)

As you can see, there is no one-rule-fits-all scenario. You have to think about what you want to create and there are no wrong answers as long as the beer tastes good when you’re done.

Dealing with Mash pH

Dropping the mash pH is as simple as either increasing the calcium content, or actually adding acid to it for paler styles. For the purposes of beginners (and this article) I would ask that you do 2 things:

1. Stick to the amount of calcium in the recipes / formulas given for now.

2. BUY A (%#!@!) PH METER!!!...and measure your mash pH 10 minutes after doughing in.

ONLY add acid if absolutely required.

3. When it comes to using acid, try using orthophosphoric acid if you can get hold of it. Lactic acid if you can’t.

4. Buy another pH meter – you can’t work without these things.

PRO TIP: Only pale and amber beers benefit from a pH of 5.2 to 5.4. To get your brown ales and stouts to have that rich flavor, aim for a mash pH of around 5.6 to 5.8. Along with residual sugars, it’ll help the final beer pH finish higher, softening that roast element into something luxurious and wonderful.

Water Profile Recipes

I have opted to use the 2008 BJCP guidelines, as they are more familiar to most than the new 2015 version. Coupled with that, Jamil Zainasheff’s book “20 Classic Styles” can be used along with the following guidelines. If you brew it and it doesn’t come out the way he describes in the book, the water chemistry is wrong and you should try again. Also, dodging the subject of alkalinity and residual alkalinity like a plague, I have expressed alkalinity as a value of bicarbonates, easily added to soft or RO water through the addition of sodium bicarbonate (baking soda). If you have water that exceeds this amount for the style you are trying to make, ditch it for a few bottles of RO or distilled water and either dilute or build from scratch. This will however bring up the subject of sodium – if so and in doubt, just try to aim for a sodium level below 100ppm unless stated otherwise.

A note on calculations and water additions:

• I am assuming you are using software to calculate your water – no one in their right mind would start off trying to manually calculate water chemistry. For this simplified version, I have opted to use BeerSmith 2 water profile calculator.

• Due to the low volume of the water homebrewers use and the fact that brewing water chemistry generally uses the same sorts of compounds, you are going to be scraping around so many small amounts of powders, it would make even the most hardened cocaine addict squirm. If you are struggling with getting the measurements right, increase the volume of water you are treating to make it both easier and more accurate – it is far easier to treat 50 gallons of water than it is to treat 5.

• Always look at the ABV and color range of your intended brew, if it’s on the higher side of the style, aim for the higher mineral content specified below, if it’s lower, aim lower.

• On many forums I have seen people arguing over the amount of residual minerals actually going into the beer and enhancing the flavor, due to boil off, mash absorption, etc, etc.

One golden rule: Less minerals is always better. When you calculate, calculate for the batch size alone i.e. you want to make 5 gallons, so you calculate on 5 gallons of water alone and never mind about the sparge. The reason is that when you boil, you concentrate everything. I’d rather you learn to err on the side of caution and get the hang of it first, instead of overdoing it and being unhappy with your result. You beer will taste great, I promise!

Let’s work through a few examples to help you to use these water profile recipes.

Scenario #1: I Want to Brew an American IPA, and I Want to Use Reverse Osmosis Water.

So I want to make a beer with, say, 70 IBU’s of bitterness, about 6 to 7% abv and the color is roughly amber. The alcohol content, firstly, and the color, secondly, ensure that I can aim for the high side of the IPA spectrum.

| Reverse Osmosis (Starting Water) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca | Mg | Na | SO4 | Cl | HCO3 | |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| American IPA (Target Water) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca | Mg | Na | SO4 | Cl | HCO3 | |

| MIN | 50 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | *50 |

| MAX | 150 | 10 | 50 | 400 | 100 | *150 |

My Preferred Additions for 5 Gallon (19 liter) Batch:

• 5g Calcium Sulphate (Gypsum)

• 1g Magnesium Sulphate (Epsom Salts)

• 2g Calcium Chloride

| My Water After Treatment | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca | Mg | Na | SO4 | Cl | HCO3 | |

| 90.3 | 5.2 | 0 | 160 | 51 | 0 |

Scenario #2: Munich Helles With Normal Tap Water (Dechlorinated, Quite Hard)

So you have water that’s not ideal for a Munich Helles…what now? Let’s have a look. Remember that everyone's tap water is different, so you will need to add your own numbers for your tap water.

| Tap Water in Antwerp, Belgium | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca | Mg | Na | SO4 | Cl | HCO3 | |

| 90 | 11 | 37 | 84 | 57 | 76 |

| 1D. Munich Helles | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca | Mg | Na | SO4 | Cl | HCO3 | |

| MIN | 50 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 50 | 0 |

| MAX | 75 | 10 | 30 | 50 | 100 | 50 |

| Tap Water Diluted | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca | Mg | Na | SO4 | Cl | HCO3 | |

| 56.3 | 6.9 | 23.1 | 52.5 | 35.6 | 47.5 |

• 4g Calcium Chloride

| My Water After Treatment | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca | Mg | Na | SO4 | Cl | HCO3 | |

| 92.1 | 6.9 | 23.1 | 52.5 | 99.1 | 0 |

Scenario #3: Bohemian Pilsner with Normal Tap Water (Dechlorinated, Very Hard)

You’re sitting with water that’s more suited to a strong stout than anything else.

| Tap Water in Dublin, Ireland | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca | Mg | Na | SO4 | Cl | HCO3 | |

| 115 | 4 | 12 | 55 | 19 | 200 |

| 2B. Bohemian Pilsner | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca | Mg | Na | SO4 | Cl | HCO3 | |

| MIN | 30 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 50 | 0 |

| MAX | 50 | 5 | 10 | 50 | 100 | 50 |

Step 2: Go to the shop and buy reverse osmosis water

Step 3: Continue as in first example.

I’m sure you get the general idea by now. If not, feel free to post in the comments section and I’ll help you out with a few more. Highly recommended further reading:

WATER: A comprehensive guide for brewers (John Palmer & Colin Kaminski)

I hope these formulas assists all those yet to take the plunge into the final frontier in the quest for the perfect pint. This really is the last step in perfection and is absolutely essential to those wishing to go commercial. I wish you the best of luck…

Light Lager

| 1A. Light American Lager | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca | Mg | Na | SO4 | Cl | HCO3 | |

| MIN | 50 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 50 | 0 |

| MAX | 50 | 10 | 30 | 50 | 100 | 50 |

| 1B. Standard American Lager | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca | Mg | Na | SO4 | Cl | HCO3 | |

| MIN | 50 | 0 | 0 | 50 | 50 | 0 |

| MAX | 75 | 10 | 30 | 150 | 100 | 50 |

| 1C. Premium American Lager | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca | Mg | Na | SO4 | Cl | HCO3 | |

| MIN | 50 | 0 | 0 | 50 | 50 | 0 |

| MAX | 75 | 10 | 30 | 150 | 100 | 50 |

| 1D. Munich Helles | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca | Mg | Na | SO4 | Cl | HCO3 | |

| MIN | 50 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 50 | 0 |

| MAX | 75 | 10 | 30 | 50 | 100 | 50 |

| 1E. Dortmunder Export | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca | Mg | Na | SO4 | Cl | HCO3 | |

| MIN | 75 | 0 | 0 | 50 | 50 | 50 |

| MAX | 150 | 10 | 30 | 150 | 100 | 100 |

Pilsner

| 2A. German Pilsner | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca | Mg | Na | SO4 | Cl | HCO3 | |

| MIN | 30 | 0 | 0 | 50 | 50 | 0 |

| MAX | 75 | 10 | 10 | 150 | 100 | 50 |

| 2B. Bohemian Pilsner | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca | Mg | Na | SO4 | Cl | HCO3 | |

| MIN | 30 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 50 | 0 |

| MAX | 50 | 5 | 10 | 50 | 100 | 50 |

| 2C. Classic American Pilsner | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca | Mg | Na | SO4 | Cl | HCO3 | |

| MIN | 30 | 0 | 0 | 50 | 50 | 0 |

| MAX | 75 | 10 | 10 | 150 | 100 | 50 |

European Amber Lager

| 3A. Vienna Lager | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca | Mg | Na | SO4 | Cl | HCO3 | |

| MIN | 50 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 50 | 50 |

| MAX | 75 | 10 | 30 | 100 | 150 | 150 |

| 3B. Oktoberfest Lager | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca | Mg | Na | SO4 | Cl | HCO3 | |

| MIN | 50 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 50 | 50 |

| MAX | 75 | 10 | 30 | 100 | 150 | 150 |

Dark Lager

| 4A. American Dark Lager | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca | Mg | Na | SO4 | Cl | HCO3 | |

| MIN | 50 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 50 | 100 |

| MAX | 75 | 10 | 0 | 50 | 150 | 150 |

| 4B. Munich Dunkel | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca | Mg | Na | SO4 | Cl | HCO3 | |

| MIN | 50 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 50 | 100 |

| MAX | 75 | 10 | 0 | 50 | 150 | 150 |

| 4C. Schwartzbier | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca | Mg | Na | SO4 | Cl | HCO3 | |

| MIN | 50 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 50 | 100 |

| MAX | 75 | 10 | 0 | 50 | 150 | 150 |

Bock

| 5A. Maibock / Helles Bock | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca | Mg | Na | SO4 | Cl | HCO3 | |

| MIN | 50 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 50 | 50 |

| MAX | 75 | 20 | 50 | 100 | 150 | 100 |

| 5B. Traditional Bock | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca | Mg | Na | SO4 | Cl | HCO3 | |

| MIN | 50 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 50 | 100 |

| MAX | 100 | 20 | 50 | 100 | 100 | 180 |

| 5C. Doppel Bock | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca | Mg | Na | SO4 | Cl | HCO3 | |

| MIN | 50 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 50 | 100 |

| MAX | 100 | 20 | 50 | 100 | 100 | 180 |

| 5D. Eisbock | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca | Mg | Na | SO4 | Cl | HCO3 | |

| MIN | 50 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 50 | 100 |

| MAX | 100 | 20 | 50 | 100 | 150 | 180 |

Light Hybrid Beer

| 6A. Cream Ale | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca | Mg | Na | SO4 | Cl | HCO3 | |

| MIN | 50 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| MAX | 100 | 10 | 20 | 50 | 100 | 100 |

| 6B. Blonde Ale | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca | Mg | Na | SO4 | Cl | HCO3 | |

| MIN | 50 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 50 | 0 |

| MAX | 100 | 10 | 20 | 200 | 100 | 100 |

| 6C. Kolsch | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca | Mg | Na | SO4 | Cl | HCO3 | |

| MIN | 50 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| MAX | 100 | 10 | 20 | 50 | 100 | 100 |

| 6D. American Wheat or Rye | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca | Mg | Na | SO4 | Cl | HCO3 | |

| MIN | 50 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| MAX | 100 | 10 | 20 | 50 | 100 | 100 |

Amber Hybrid Beer

| 7A. Northern German Altbier | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca | Mg | Na | SO4 | Cl | HCO3 | |

| MIN | 50 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 50 | 50 |

| MAX | 100 | 10 | 30 | 300 | 100 | 150 |

| 7B. California Common | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca | Mg | Na | SO4 | Cl | HCO3 | |

| MIN | 50 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 50 | 50 |

| MAX | 100 | 10 | 30 | 300 | 100 | 150 |

| 7C. Dusseldorf Altbier | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca | Mg | Na | SO4 | Cl | HCO3 | |

| MIN | 50 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 50 | 50 |

| MAX | 100 | 10 | 30 | 300 | 100 | 150 |

English Pale Ale

| 8A. Standard / Ordinary Bitter | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca | Mg | Na | SO4 | Cl | HCO3 | |

| MIN | 50 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 50 | 0 |

| MAX | 150 | 10 | 30 | 200 | 100 | 180 |

| 8B. Special / Best Premium Bitter | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca | Mg | Na | SO4 | Cl | HCO3 | |

| MIN | 50 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 50 | 0 |

| MAX | 150 | 20 | 50 | 200 | 100 | 180 |

| 8C. English Pale Ale | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca | Mg | Na | SO4 | Cl | HCO3 | |

| MIN | 50 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 50 |

| MAX | 150 | 10 | 30 | 400 | 100 | 150 |

Scottish and Irish Ale

| 9A. Scottish Light 60 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca | Mg | Na | SO4 | Cl | HCO3 | |

| MIN | 50 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 50 | 50 |

| MAX | 150 | 20 | 50 | 200 | 100 | 180 |

| 9B. Scottish Heavy 70 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca | Mg | Na | SO4 | Cl | HCO3 | |

| MIN | 50 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 50 | 50 |

| MAX | 150 | 20 | 50 | 200 | 100 | 180 |

| 9C. Scottish Export 80 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca | Mg | Na | SO4 | Cl | HCO3 | |

| MIN | 50 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 50 | 50 |

| MAX | 150 | 20 | 50 | 200 | 100 | 180 |

| 9D. Irish Red | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca | Mg | Na | SO4 | Cl | HCO3 | |

| MIN | 50 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 50 | 50 |

| MAX | 100 | 10 | 20 | 300 | 100 | 150 |

| 9E. Wee Heavy (Strong Scotch Ale) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca | Mg | Na | SO4 | Cl | HCO3 | |

| MIN | 50 | 0 | 0 | 50 | 50 | 50 |

| MAX | 150 | 30 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 150 |

American Ale

| 10A. American Pale Ale | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca | Mg | Na | SO4 | Cl | HCO3 | |

| MIN | 50 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| MAX | 150 | 10 | 20 | 400 | 100 | 150 |

| 10B. American Amber Ale | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca | Mg | Na | SO4 | Cl | HCO3 | |

| MIN | 50 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 50 | 50 |

| MAX | 100 | 20 | 30 | 300 | 100 | 150 |

| 10C. American Brown Ale | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca | Mg | Na | SO4 | Cl | HCO3 | |

| MIN | 50 | 0 | 0 | 50 | 50 | 100 |

| MAX | 75 | 30 | 50 | 150 | 150 | 200 |

English Brown Ale

| 11A. Mild | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca | Mg | Na | SO4 | Cl | HCO3 | |

| MIN | 50 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 50 | 50 |

| MAX | 150 | 20 | 30 | 200 | 100 | 150 |

| 11B. Southern English Brown | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca | Mg | Na | SO4 | Cl | HCO3 | |

| MIN | 50 | 0 | 0 | 50 | 50 | 100 |

| MAX | 75 | 30 | 50 | 150 | 150 | 200 |

| 11C. Northern English Brown | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca | Mg | Na | SO4 | Cl | HCO3 | |

| MIN | 50 | 0 | 0 | 50 | 50 | 100 |

| MAX | 75 | 30 | 50 | 150 | 150 | 200 |

Porter

| 12A. Brown porter | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca | Mg | Na | SO4 | Cl | HCO3 | |

| MIN | 50 | 10 | 0 | 50 | 50 | 100 |

| MAX | 75 | 30 | 50 | 150 | 150 | 200 |

| 12B. Robust porter | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca | Mg | Na | SO4 | Cl | HCO3 | |

| MIN | 50 | 10 | 0 | 50 | 50 | 100 |

| MAX | 75 | 30 | 50 | 150 | 150 | 200 |

| 12C. Baltic porter | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca | Mg | Na | SO4 | Cl | HCO3 | |

| MIN | 50 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 50 | 100 |

| MAX | 100 | 20 | 80 | 100 | 150 | 250 |

Stout

| 13A. Dry Irish Stout | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca | Mg | Na | SO4 | Cl | HCO3 | |

| MIN | 50 | 0 | 0 | 50 | 50 | 100 |

| MAX | 75 | 30 | 100 | 150 | 150 | 200 |

| 13B. Sweet Stout | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca | Mg | Na | SO4 | Cl | HCO3 | |

| MIN | 50 | 10 | 20 | 50 | 50 | 100 |

| MAX | 75 | 30 | 100 | 150 | 150 | 200 |

| 13C. Oatmeal Stout | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca | Mg | Na | SO4 | Cl | HCO3 | |

| MIN | 50 | 10 | 20 | 50 | 50 | 100 |

| MAX | 75 | 30 | 100 | 150 | 150 | 200 |

| 13D. Foreign Extra Stout | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca | Mg | Na | SO4 | Cl | HCO3 | |

| MIN | 50 | 10 | 20 | 50 | 50 | 100 |

| MAX | 75 | 30 | 150 | 150 | 150 | 250 |

| 13E. American Stout | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca | Mg | Na | SO4 | Cl | HCO3 | |

| MIN | 50 | 10 | 20 | 50 | 50 | 100 |

| MAX | 75 | 30 | 150 | 150 | 150 | 250 |

| 13F. Russian Imperial Stout | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca | Mg | Na | SO4 | Cl | HCO3 | |

| MIN | 50 | 10 | 20 | 50 | 50 | 150 |

| MAX | 75 | 30 | 150 | 150 | 150 | 250 |

IPA

| 14A. English IPA | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca | Mg | Na | SO4 | Cl | HCO3 | |

| MIN | 50 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 50 | 50 |

| MAX | 150 | 10 | 50 | 300 | 100 | 150 |

| 14B. American IPA | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca | Mg | Na | SO4 | Cl | HCO3 | |

| MIN | 50 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | *50 |

| MAX | 150 | 10 | 50 | 400 | 100 | *150 |

| 14C. Imperial IPA | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca | Mg | Na | SO4 | Cl | HCO3 | |

| MIN | 50 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 50 | *50 |

| MAX | 150 | 10 | 50 | 300 | 100 | *150 |

German Wheat or Rye

| 15A. Weizen | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca | Mg | Na | SO4 | Cl | HCO3 | |

| MIN | 50 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 50 | 0 |

| MAX | 100 | 20 | 30 | 50 | 100 | 100 |

| 15B. Dunkel Weizen | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca | Mg | Na | SO4 | Cl | HCO3 | |

| MIN | 50 | 0 | 0 | 50 | 50 | 100 |

| MAX | 75 | 30 | 100 | 150 | 150 | 200 |

| 15C. Weizen Bock | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca | Mg | Na | SO4 | Cl | HCO3 | |

| MIN | 50 | 10 | 0 | 50 | 50 | 150 |

| MAX | 75 | 30 | 150 | 150 | 150 | 250 |

| 15D. Roggenbier | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca | Mg | Na | SO4 | Cl | HCO3 | |

| MIN | 50 | 0 | 0 | 50 | 50 | 50 |

| MAX | 75 | 30 | 30 | 150 | 150 | 200 |

Belgian and French Ale

| 16A. Witbier | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca | Mg | Na | SO4 | Cl | HCO3 | |

| MIN | 50 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 50 | 0 |

| MAX | 100 | 20 | 30 | 50 | 100 | 100 |

| 16B. Belgian Pale Ale | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca | Mg | Na | SO4 | Cl | HCO3 | |

| MIN | 50 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 50 | 0 |

| MAX | 150 | 20 | 20 | 300 | 100 | 150 |

| 16C. Saison | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca | Mg | Na | SO4 | Cl | HCO3 | |

| MIN | 50 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| MAX | 150 | 20 | 20 | 300 | 100 | 150 |

| 16D. Bier De Garde | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca | Mg | Na | SO4 | Cl | HCO3 | |

| MIN | 50 | 0 | 0 | 50 | 50 | 50 |

| MAX | 100 | 30 | 100 | 100 | 150 | 150 |

Sour Ale

*Minerals don’t have a huge impact on sour beers, due to all the bugs we add in there. Your concentration should be on enough calcium to get your mash Ph down and that’s about it. If you are still not sure, generally aim for the lower end of the spectrums provided.

| 17A. Berliner Weisse | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca | Mg | Na | SO4 | Cl | HCO3 | |

| MIN | 50 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| MAX | 100 | 5 | 0 | 50 | 100 | 0 |

| 17B. Flanders Red | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca | Mg | Na | SO4 | Cl | HCO3 | |

| MIN | 50 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| MAX | 100 | 10 | 0 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| 17C. Oud Bruin | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca | Mg | Na | SO4 | Cl | HCO3 | |

| MIN | 50 | 0 | 0 | 50 | 50 | 50 |

| MAX | 100 | 10 | 50 | 100 | 150 | 200 |

| 17D. Lambic | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca | Mg | Na | SO4 | Cl | HCO3 | |

| MIN | 50 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 50 | 0 |

| MAX | 150 | 10 | 20 | 100 | 100 | 0 |

| 17E. Geueze | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca | Mg | Na | SO4 | Cl | HCO3 | |

| MIN | 50 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 50 | 0 |

| MAX | 150 | 10 | 20 | 100 | 100 | 0 |

| 17F. Fruit Lambic | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca | Mg | Na | SO4 | Cl | HCO3 | |

| MIN | 50 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 50 | 0 |

| MAX | 150 | 10 | 20 | 100 | 100 | 0 |

Belgian Strong Ale

| 18A. Belgian Blonde | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca | Mg | Na | SO4 | Cl | HCO3 | |

| MIN | 50 | 0 | 0 | 50 | 50 | 0 |

| MAX | 100 | 10 | 30 | 100 | 100 | 50 |

| 18B. Belgian Dubbel | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca | Mg | Na | SO4 | Cl | HCO3 | |

| MIN | 50 | 5 | 0 | 50 | 50 | 50 |

| MAX | 100 | 20 | 50 | 100 | 150 | 150 |

| 18C. Belgian Tripel | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca | Mg | Na | SO4 | Cl | HCO3 | |

| MIN | 50 | 0 | 0 | 50 | 50 | 0 |

| MAX | 100 | 10 | 30 | 100 | 100 | 50 |

| 18D. Belgian Golden Strong Ale | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca | Mg | Na | SO4 | Cl | HCO3 | |

| MIN | 50 | 0 | 0 | 50 | 50 | 0 |

| MAX | 100 | 10 | 30 | 100 | 100 | 50 |

| 18E. Belgian Dark Strong Ale | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca | Mg | Na | SO4 | Cl | HCO3 | |

| MIN | 50 | 0 | 0 | 50 | 50 | 100 |

| MAX | 100 | 30 | 150 | 150 | 150 | 250 |

Strong Ale

| 19A. Old Ale | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca | Mg | Na | SO4 | Cl | HCO3 | |

| MIN | 50 | 10 | 0 | 50 | 50 | 50 |

| MAX | 75 | 30 | 150 | 150 | 150 | 250 |

| 19B. Barley Wine | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca | Mg | Na | SO4 | Cl | HCO3 | |

| MIN | 50 | 10 | 0 | 50 | 50 | 50 |

| MAX | 100 | 30 | 100 | 100 | 150 | 150 |

| 19C. American Barley Wine | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca | Mg | Na | SO4 | Cl | HCO3 | |

| MIN | 50 | 10 | 0 | 50 | 50 | 50 |

| MAX | 100 | 30 | 100 | 100 | 150 | 150 |

Fruit Beer

Look at the base style of the beer and use the guidelines associated with that beer.

Spice Herb or Vegetable Beer

Look at the base style of the beer and use the guidelines associated with that beer.

Smoked or Wood Aged Beer

| 22A. Rauchbier | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca | Mg | Na | SO4 | Cl | HCO3 | |

| MIN | 50 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 50 | 50 |

| MAX | 75 | 10 | 30 | 100 | 150 | 150 |

Specialty Beer

Have a look at the beer you are trying to create. Match the colour, bitterness, alcohol content to another beer on the styles list. Use the one you think fits closest to that style.