tagging

@Northern_Brewer and

@Peebee (a couple of brewers on "the other side of the pond") to see if they can help with identifying beers or beer styles that match what you are trying to replicate.

Sorry for the slow response - but although the big British thread here is great, if you're serious about this stuff you're better off crossing the pond to HBT's transatlantic cousin at

www.thehomebrewforum.co.uk

The time I was struck by the abv:flavor ratio, I was at the Lamb & Flag in Oxford; I just checked, and I didn't recognize any names, so I think they must have different beers on tap right now.

But I can say this much: there weren't very bitter--far from a hardcore IPA--and yet they were quite flavorful, not watery at all.

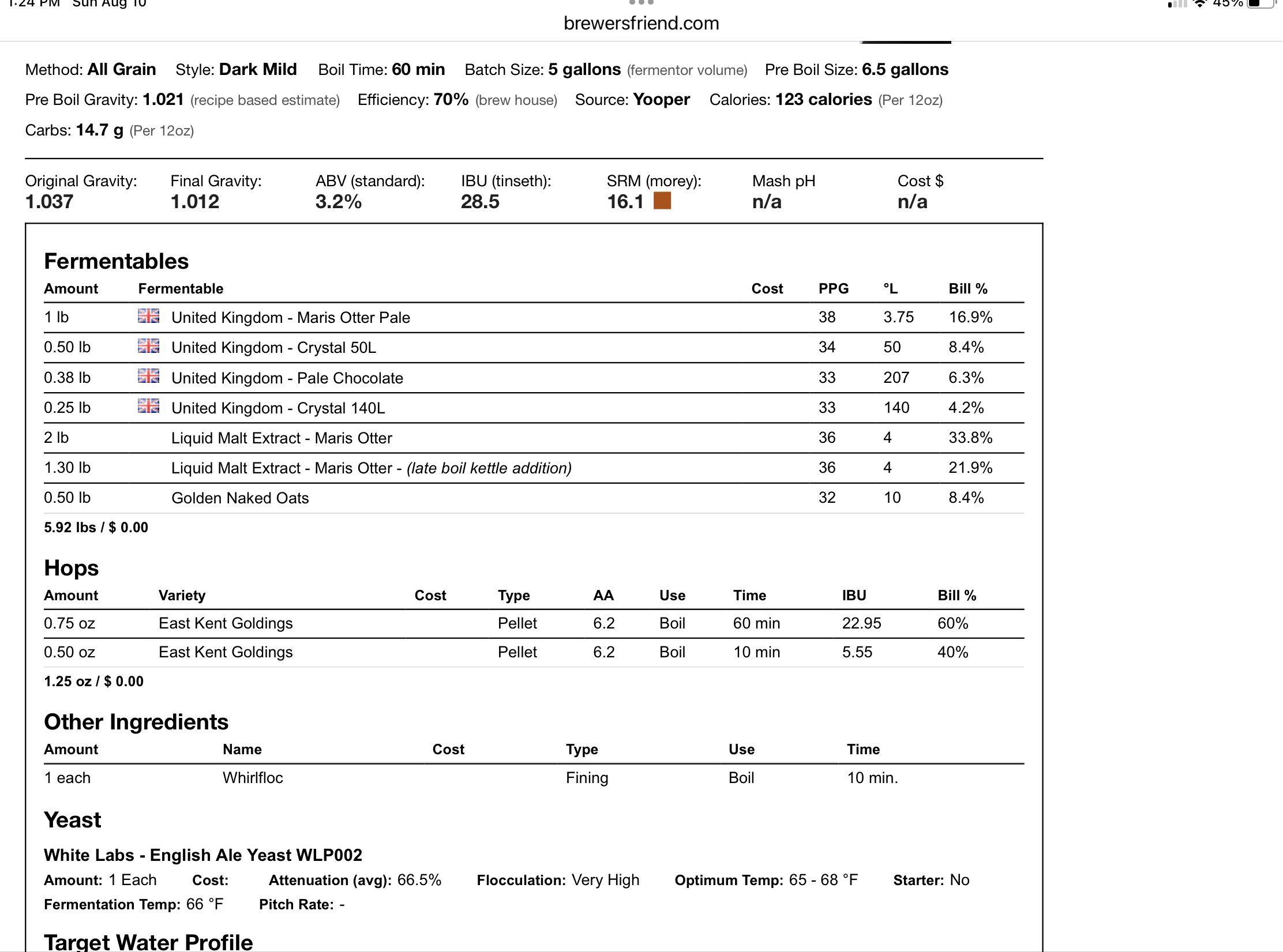

Assuming those beers / beer styles can be identified (or at least agreed upon), and a likely recipe is available, the next step will be to try to convert from "all-grain" to "DME" or "partial mash"....my thought is to find a couple of all-grain recipes for the beers you want to replicate and then the HomeBrewTalk community can offer opinions on how to convert the recipes from all-grain to DME or partial mash.

The trouble is that the Lamb & Flag is a free house, which means it makes a point of avoiding the big-name breweries that USians will recognise and whose beers are the ones that people try to clone. And they also make a point of rotating them, but you may be able to see one you recognise by looking at

their Untappd reviews for a week either side of when you were there.

However they are Untappd members so we can check out

the current menu, and their

CAMRA Whatpub entry, which tell us their regular casks are XT Four (badged as Inklings Ale) and Prospect from Oxford Brewery.

Four is a 3.8% "modern session amber ale" with Cascade and Bramling Cross, (Shotover) Prospect is a 3.7% paler "

session bitter, lower in alcohol, yet big in body and flavour. It delivers a surprisingly big mouthfeel and a striking dry hoppiness" and "

Mild bitterness, dry hoppiness and hint of toffee...Smell: Toast, mildly fruity with a touch of honey" although they're a bit vague about what's in it beyond "a variety of malts with New World and English hops". Usually you can identify the big name cereals used (so the "extras" like wheat, oats etc) by the legally mandated allergen notice, but naughtily they don't have it. But even if you didn't want them to tell you a recipe, they wouldn't be surprised to have someone ask about allergens.

It's a bit unusual to have two brown-ish bitters under 4% as your core beers, most typically you see a yellow bitter of 3.8% with New World hops and an amber best of 4.2% with British hops. At the moment they obviously have enough trade to sustain seven beers on cask (which is A Lot), so they can have fun over 4%, then fall back to a more limited offer outside the tourist season. Certainly there's a lot of British pubs which don't normally have any cask beer over 4.5% as they just can't sell enough of it within the limited lifespan of cask, I know some where it's an explicit rule that they don't go over 4.5%, it's only in city centres that it really works.

Oxford is not my neck of the woods so I don't know the breweries there well, but I guess what they're doing with the two core beers is the two extremes of trad amber bitter, the Prospect is more of a "northern" style with "dry hoppiness", and Four will be more of a typical Thames Valley style with more crystal and less bitterness. But looking at the current menu it's mostly yellow, something like Double-Barrelled's Skyline is the kind of thing you'll see a lot of on cask in British pubs, a 4% pale with Columbus, Citra and Centennial. Then two more trad options at 4.2% and 5%, a rye beer as the "oddity", and a lactose stout to complement the Guinness equivalent on keg, a 4.4% stout from XT.

So other than the lactose stout being over 5%, their current beer list is all pretty standard cask for a beer-forward pub here.

"Keeping it simple" sounds great. But would it then be less flavorful?

I lean more on the fuller specialty grains (120°, Special B, debittered black malt, etc.) for increased flavor and add some maltodextrin for mouthfeel.

So I would expect going from ~5.3% to ~4.3% would still be enjoyable...

It's a classic mistake, to overcomplicate these things. If you look at

actual British recipes, they are generally pretty simple, although commercial beers may use similar ingredients from multiple sources just to ensure consistency and reduce the impact of something becoming unavailable. It's as much about process as recipe. Like classic British cooking, it's about taking a few good quality ingredients and letting them shine, rather than using lots of ingredients in an attempt at "complexity" and ending up with a muddle. Personally, the entire malt inventory for 90% of the British beers I make (at 4-4.5%) is - a sack of Maris Otter pale malt, and that's it. Ideally Warminster, usually I end up with Fawcett or Simpson, I'm not so keen on the East Anglian maltsters like Munton & Crisp. Maybe I add 5% torrefied wheat for head if I'm feeling fancy, but generally I don't really need it.

I'd listen to people like the legendary James Kemp, one of the co-founders of Cloudwater (at one point second in the world on Ratebeer behind Hill Farmstead). He explicitly rejects complex malt bills for these beers :

https://web.archive.org/web/2018041...co.uk/yeast-brewing-myths-ideal-house-strain/

what is it about [trad bitter]

that makes them so interesting and amazing? I’d thought for a while that it was malt character and quality and especially malt complexity that help create such an interesting beer at a modest abv. This was certainly a tack I tried to take when I was brewing commercially but when you look at these beers and their recipes you’ll find them to be simple and very much the same....This really doesn’t leave much else apart from yeast and that in fact I think is the key, traditional British beers, even though they are fairly ubiquitous are exceptional because the main character building ingredient is the yeast....

From a lifetime drinking this kind of beer, and fewer years of trying to brew them, I would say that there's a real sweet spot around the best strength of ~4.2-4.3%, it gets a lot harder once you go below 4%. Still possible to make great beer, but exponentially more difficult. But that's OK, because you're not meant to think too much about <4% beer, it's for downing by the (imperial) gallon whilst spending a night talking with your mates. Anyway, in the first instance I would aim for 4.2-4.3%.

Having drunk quite a bit of US attempts at British styles, I'd say the major things US brewers (with a handful of notable exceptions) get wrong :

The big one is they almost always end up too sweet, they have this idea British beers are quite sweet and under-attenuated, possibly from drinking in London tourist pubs that don't condition their beer properly. One reason is that they think that all the colour comes from crystal, when it's normal to use caramel or black malt to bring the colour up to a consistent level for commercial reasons. It doesn't help that tourists seldom stray from the Thames valley where beers tend to be more crystal heavy but we have recipes and even the Fuller's partigyle (Pride, ESB etc) is only

7.2% light crystal, whereas up north

they may not use any crystal at all.

That's part of a wider theme, that British beers are all about balancing all the ingredients, you shouldn't be going for extremes. And one of the most important ingredients that USians tend to get wrong is carbonation. Too much and it just overwhelms modest beers, turning them into a mess of carbonic acid. So go easy on the carbonation. It's easy to laugh at CAMRA's obsession with dispense, but you only have to compare (force-carbed) Coca-Cola with (naturally yeast-carbonated) fancy sparkling wine like champagne to see the difference in bubble size, which completely changes the mouthfeel. It's not true for all beers - I know different beers which are best served in can, cask, bottle or keg - but cask does suit a lot of these lower-ABV beers. And I think one thing that the prevalence of cask here has given us, is an awareness of how carbonation affects beer which follows through when eg canning hoppy New World-style beers. OTOH that doesn't mean cask-conditioned beer is as dead as it usually is in London tourist pubs, it still has "condition" (and I've had the cellar showers to prove it), but you want to be in the range of 1.6-1.8 vol CO2, maybe a touch more for bottles.

Whilst on dispense - serving cold kills these beers. That doesn't mean they're served "warm" as legend has it, but too cold definitely kills them. The official recommendation is for cask beer to be kept at 12-14°C (54-57°F), personally I like to serve a touch lower than that and let it warm up in the glass through the official sweet spot, but we're talking 10-11°C (50-52°F) not fridge temperature. These differences may seem small, but I know a town where one CAMRA pubs has its cellar at 12°C (54°F) and the other at 14°C (57°F), and locals talk about one having "cold" beer and the other having "warm" beer, depending on their personal preference! To be fair if you were here during the recent heatwaves then a lot of cellars were struggling to maintain temperature....

I was in England this past summer, and I was impressed with the very flavorful beers that had low alcohol content--like around 4%.

What I almost always do is brew with Briess DME, 5lbs for 4 gallons of water, and then vary the hops to keep it interesting. Typically my yeast is Safale-05. The result is, to me, normally quite nice, but the alcohol content is pretty high--I never test it, but you can tell by drinking it!

I was thinking I need to use different yeast (yeast that gives up sooner?), or cut back on the DME and then make up for it by using more hops or specialty grains. But maybe I'm completely barking up the wrong tree.

You don't want "yeast that gives up sooner", or with less attenuation as it's called in brewer-speak. It's another myth in the US that British yeasts have low attenuation, in reality it's that dryness that helps makes the beer so moreish and sessionable, 77-82% attenuation is quite common and some classic beers have

attenuation over 90%, albeit with the help of some sugar in the recipe. And you shouldn't need to "make up" for less DME with hops or speciality grains - the cheat code you are looking for is "use British ingredients" as they're more flavourful to start with. Notably we have more flavourful barley - in particular malts from single varieties like Maris Otter and Golden Promise - and base malts are kilned for longer to give a bit more toastiness. Conversely, for now I would avoid any pilsner/"*extra* pale malts as they will give you less flavour and body.

Now you're at a disadvantage if you only use malt extract (aside from it being a lot more expensive per batch), as there's a lot less choice. In particular I think the only single-variety malt extract is Munton's Maris Otter liquid malt extract (LME), and LME stales quickly so you only want to get it from sources that you know have the turnover to keep it relatively fresh. Alternatively you need to get into all-grain brewing, which will open the doors to a full range of malts, and lower costs per batch, albeit at the expense of a relatively modest up-front cost. You can get all complicated, but all you need for basic brew-in-a-bag (BIAB) is a net bag, a way to heat water/wort, and a way to monitor (and ideally control) the temperature. There's lots of advice on BIAB around this place, so I won't go into more detail here.

It's a similar story with yeast - there's no great English-style dried yeasts, although a lot of beer is made commercially with the likes of Nottingham, S-O4 and Windsor (the latter usually mixed with one of the former). Mangrove Jack M36 Liberty Bell is probably a mix of Notty and Windsor and as such is a safe bet if you're restricting yourself to dried. Two AEB yeast (sold in the US under the Cellar Science and Apex brands) that may be worth trying are their New-E (which claims to be a dried London Ale III type) and the plain Fermoale (not Fermoale AY3 etc) allegedly from Tetley. A more leftfield option might be Fermentis BE-256 which although marketed as Belgian has roots in England, maybe mixed with a bit of T-58 for some phenolics for interest. But I would strongly encourage you to split a batch and ferment the same wort with different yeasts, to get an idea of what each brings to the party - a lot of it is just personal taste.

Going to all-grain over extract is more of a priority, but liquid yeasts give you a lot more choice of British strains - Wyeast 1469 and Imperial Pub are good places to start; I have a bit of a soft spot for WLP041 - not flashy, but makes really nice sessionable beer. Of course we're spoilt here in the UK as supermarkets have fresh Fuller's 1845, bottle-conditioned with the production yeast, or we can get cask dregs from pubs. And if you want to go to the next level, Brewlabs have all the best strains as slopes....

https://www.themaltmiller.co.uk/product-category/ingredients/yeast/brewlab-yeast-slopes/

https://brewlab.co.uk/services/yeast-list/

But don't worry too much about that just yet.

So I got the following going yesterday: 3 gallons of water + 3# Briess Light Pilsen (the very last of my DME) + 1.25 oz Cascade (20 min) + 1.25 oz Cascade (5 min) + Safale05.

The Light Pilsen is

described by Briess as "

the lightest pure malt extract available commercially" - not what you want if you're looking to maximise body. Even if you can't readily get British DME (aka "spraymalt"), at least use Briess Pale Ale DME, or even their Munich LME, rather than the Pilsen. And personally I'd push the hops a bit later, there's no point boiling away all the flavour compounds; I tend to smear a 100g pack over 10min/flameout/whirlpool/dryhop.

I should probably stop there. But I'll leave you with some more reading from Jeff Alworth :

A celebration of cask beer :

https://www.beervanablog.com/beervana/2018/10/12/the-worlds-most-crafted-beer-is-cask-ale

Discovering "juicy bitter" in a series of articles in late 2019 starting with :

https://www.beervanablog.com/beervana/2019/9/10/juicy-bitter-on-cask

An article on making modern bitter, and an associated blog which goes into more detail :

https://beerandbrewing.com/style-school-cask-bitter/

https://www.beervanablog.com/beervana/2025/4/7/the-evolution-of-cask-bitter

![Craft A Brew - Safale S-04 Dry Yeast - Fermentis - English Ale Dry Yeast - For English and American Ales and Hard Apple Ciders - Ingredients for Home Brewing - Beer Making Supplies - [1 Pack]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/41fVGNh6JfL._SL500_.jpg)