There are of course a few different enzymes that apply to "protein rests." Proteinase is the enzyme most active at higher temperatures relative to the others. The optimum range for this enzyme is 122F-138F. Typically a rest intended for this enzyme is done somewhere around 131F-136F. Like all enzymes involved with mashing, it will remain active (although not efficiently) at higher temperatures until it denatures. Think of the temperature range for enzymes as a gradient, which overlaps with the enzymes that are active both below and above its optimum temperature range.My understanding (seemingly mistaken) was that the top end of the temp range for a protein rest was just under 130F.

Edited to add: This is why temperature still matters for single infusion mashing. Beta and alpha amylase have an overlap, and are both active at single infusion temperatures. Beta amylase conversion is more prevalent in the 147-154F range than it is in the 156-160F range. Not that beta amylase works slower at those higher temps, but that alpha amylase works incredibly fast at those temps and will convert more of the starches before beta gets a decent chance. The two do not work the same, either. Beta works slower, but does a "neater" job and cuts starch chains into nice mono- and disaccharides that are easily fermented by S. cerevisiae. Alpha amylase works quite fast, but is "sloppy" and just rips through starch chains, leaving more polysaccharides that are less fermentable by S. cerevisiae. The desired balance between fermentability and body of the resultant beer is what dictates the temperature at which you rest your mash, which dictates the proportional activity of alpha and beta amylase.

As stated in my previous post, unless your particular malt specifies that it is under-modified, it is assumed to be fully modified. In which case any protein rests are not recommended. Wheat malts do tend to have higher protein content, but fully modified wheat malts still do not require a protein rest. If you are using unmalted wheat, then beta-glucanase and proteinase rests are recommended.My next possibly mistaken assumption was that certain malts, primarily pilsner and wheat, benefited from a rest at about 131F and then sacch rest somewhere between 148 and 156 depending on the profile you want. Is this accurate?

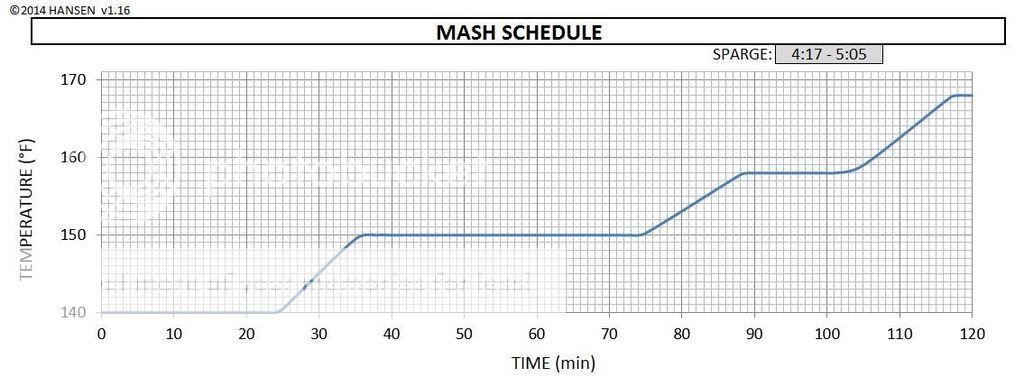

As for the sacch rest(s), that will be up to the brewer to determine what rest(s) they want to achieve their desired result. Generally speaking, saccharification occurs between 140F-160F. The actual range of activity for beta and alpha amylase is a bit wider than that, but that's another topic. If you are doing a single infusion rest, choose the temperature that you feel will reflect an appropriate balance between beta and alpha amylase. If you want to do a step mash, you can choose your beta rest, a combined rest, and an alpha rest (or any combination of these). If you're doing a ramp mash, strike in the beta amylase range, then slowly raise the temperature through the alpha amylase range, into a mashout (168F).

It most certainly can be detrimental unless it says anywhere on your malt sack (or better yet - the malt house datasheet) that it is under-modified. I doubt you are using under-modified malts unless you either set out to buy them or bought them on accident.I've always done a rest at 131F for these. That's why I started my ramp up there for this BDSA with Belgian pilsner. Does this have any benefit (or detriment) for either wheat malt or pilsner?

Not always, no. For example, I use Warminster Maris Otter malt frequently, which is floor malted (it says so on the sack). It is, however, fully modified and suited for single infusion saccharification. If you're not sure, ask to see the datasheet on your malt from your LHBS, or you can look it up on the maltster's website.If a grain is called "floor malted" does that always mean it's undermodified? I've seen the term on some on the grain bags at my LHBS but never really thought about it.

Yes. Regardless of what other recipes say, skip the protein rests when you are using fully modified malts. And indeed that does include your typical (fully modified) wheat malts.There are a lot of recipes on this site and elsewhere that call for a rest in the low 130's. Almost none of them specify undermodified malts. I have a number of my recipes that call for this rest for wheat beers, lagers or pretty much anything with pils. Should I shift these to a 140F rest? Just to be clear, when I say wheat I mean malted wheat, not torrified or flaked.

It's quite possible that you haven't noticed any detriment, and for many reasons. Look at it this way; as you pointed out, you're not a certified judge. Maybe you couldn't tell the difference and others might have. Or perhaps the difference might have been more obvious if you had a control sample to compare it to (same brew, but without the protein rest). You also may not have held the protein rest long enough for serious degradation of medium length protein chains. Or, although not as likely, you may have gotten a slightly less modified batch of malt (this is very rare from the larger producers).I've never noticed an issue with head or mouthfeel with my multi-step mashes but I'm also not a BJCP judge. If a simple change in mash schedule can help me make better beer, I'll take it any day. Thanks for the education.

If you stay above 140F with your fully modified malts, all you need to concern yourself with are your saccharification rests and the lautering process. I promise that you'll get all the great benefits of step mashing without having to worry about the mouthfeel or head retention. Here is an example of a recipe of mine using a step mash starting at 140F that won a first place award in a competition. Go ahead, give it a try!

Thanks for hearing me out. Hope this helps!

![Craft A Brew - Safale BE-256 Yeast - Fermentis - Belgian Ale Dry Yeast - For Belgian & Strong Ales - Ingredients for Home Brewing - Beer Making Supplies - [3 Pack]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/51bcKEwQmWL._SL500_.jpg)