For a lager fermenting at 50° F, what temperature do you recommend for a diacetyl rest?

In my experience if you ferment at 48 °F to within 1 °P or so of expected terminal gravity and then from that point slowly lower to near freezing and hold there for a couple of weeks you won't need a diacetyl rest. No one ever comments on diacetyl in beer made this way to the point I've quit measuring it because it is a big PITA to do so and the result was always that it was right at threshold. Plus, and this is important in looking at plots like the one posted by Malticulous, the common hydroxylamine/glyoxime test picks up acetolacte (the precursor) as well as diacetyl. This is really good though because the goal is have diacetly at threshold or below

and to keep acetolactate (which will turn into diacetyl once the yeast are removed) out of the package.

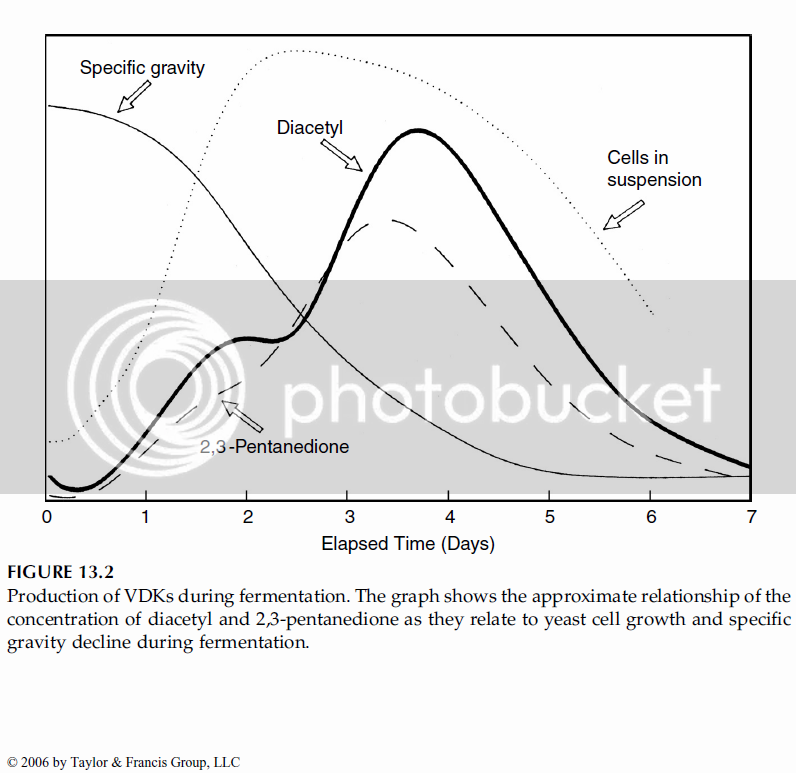

Diiacetyl is not produced by the yeast but acetolactate is. Acetolactate is non-enzymatically oxidized to diacetyl external to the cell after fermentation has peaked. Uptake (two reductions to respectively acetoin and 2,3, butane diol) do take place within the cell. All methods of diactyl reduction thus require active yeast. In modern mega brewing yeast activity is insured by raising the temperature and the amount of diacetyl/acetolactate goes down but note that there is a residual. There is no scale on the graph but we must presume that the reduction is to threshold or lower as once the yeast is removed diacetyl reduction is over but diacetyl production can continue.

The graph represents typical modern megabrewing practice. Beer which approaches, at least to Joe Sixpack, beer made by the traditional method, is produced in a week!. This is a remarkable technological achievement but there is a downside. I liken the modern brewing industry to the modern motion picture industry. The technology is amazing but the overall result is insipid.

By contrast in the traditional method the nearly finished beer is gently cooled to avoid shocking the yeast and transferred to the lagering vessel with plenty still in suspension. Over the next few months the yeast cells, still active at near freezing temperature, reduce diacetyl, acetaldehyde and jungbuket and keep the beer in a reduced state (low ORP) with the final result being a better product. Flavors are melded, mellowed, smoothed and rounded and, though I can't begin to explain it, the CO2 melds as well. Properly lagered beer is never "fizzy".

In my own brewing I go straight to the keg after cold conditioning for about 3 weeks. The first keg goes on tap immediately and one of the most fascinating things about the process is frequent sampling of the beer thereafter. Often it is good at the outset (in fact we sometimes drink it from the Zwickle) but it is definitely "green". What's interesting is that it stays green and stays green ans stays green and then turns overnight. At this point (usually about 3 weeks in) it is pretty clear and definitely ready to drink. But the show isn't over yet. It will continue to improve for up to a year and, as I mentioned before, that is because it is sitting on the yeast. The improvement isn't always monotonic but it usually is and, as I noted in an earlier post, eventually comes to an end. If I've planned well that's about the time the last keg runs out.

If, at any time in all of this, you need to pull off some beer for a party, to put into a contest or whatever, you just do that. That beer is then off the yeast and needs to be consumed fairly quickly as the yeast are no longer there to stabilize it and, if you went to bottles, you introduced some air which the yeast aren't there to scavenge.

Perhaps I could summarize by saying that beer stored on living yeast is a living thing i.e. it has a life of its own. Following that life cycle is, for me, one of the most enjoyable and fascinating aspects of brewing. Clearly this post represents some personal preferences and these are, obviously, influenced by personal taste. I am not saying that the high temp/diacetyl rest program should not be used. I'm just saying it's not right for me. If you prefer beer made that way then by all means make it that way. The final word: if lager fermentation and lagering are carried out properly there is no need for a diacetyl rest.