You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

The State of Low Oxygen Brewing: On Progress, Updates and Review

- Thread starter Big Monk

- Start date

Help Support Homebrew Talk - Beer, Wine, Mead, & Cider Brewing Discussion Forum:

This site may earn a commission from merchant affiliate

links, including eBay, Amazon, and others.

The category is gambling, so I can't view it at work

Big Monk

Trappist Please! 🍷

- Joined

- Dec 24, 2015

- Messages

- 2,192

- Reaction score

- 1,151

The category is gambling, so I can't view it at work

Yeah it took us a while to figure out that some people's network's erroneously categorize the postings.

Nothing we can really do as it's an issue with certain networks and varies from case to case.

Take a look later!

MSK_Chess

enthusiastic learner

We have revised the "Methods of the Low Oxygen Brewhouse" paper and put together an update and review of the current state of the methods here:

http://www.********************/brewing-methods/low-oxygen-review/

Very interesting. I liked the use of sour beer to acidify the mash. On what basis are you making the claim that you are the first to use it, 'Being the first we know of that started using it'. I doubt this can be historically substantiated.

The category is gambling, so I can't view it at work

You need to turn off the Sophos Web Intelligence Service on your work computer.

Start -> Run -> Services.msc [enter]

Stop and disable any service starting with "Sophos Web"

Don't ask me how I know this...

MSK_Chess

enthusiastic learner

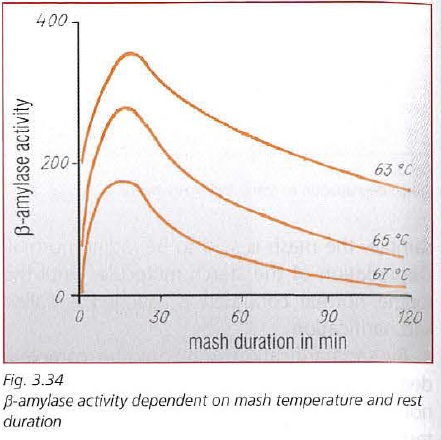

The Brauwelt article is amazing. Had no idea that Beta amylase had such a short life.

The rather short half-life of β-amylase

at such temperatures (approx. 18.5 min at

62 °C and 9.3 min at 64 °C) brings about a

fairly rapid loss in its activity (fig. 2). By the

time the mash reaches 67 °C, there is prac-

tically no β-amylase activity. Thus, from

the standpoint of increasing the maltose

content of the wort, the rest at 67 °C can be

deemed largely superfluous.

Wow!

The rather short half-life of β-amylase

at such temperatures (approx. 18.5 min at

62 °C and 9.3 min at 64 °C) brings about a

fairly rapid loss in its activity (fig. 2). By the

time the mash reaches 67 °C, there is prac-

tically no β-amylase activity. Thus, from

the standpoint of increasing the maltose

content of the wort, the rest at 67 °C can be

deemed largely superfluous.

Wow!

Big Monk

Trappist Please! 🍷

- Joined

- Dec 24, 2015

- Messages

- 2,192

- Reaction score

- 1,151

Very interesting. I liked the use of sour beer to acidify the mash. On what basis are you making the claim that you are the first to use it, 'Being the first we know of that started using it'. I doubt this can be historically substantiated.

We aren't saying that we are the first people to ever use Sauergut, just that we are the first to use it in this setting AND have spreadsheet based calcs that incorporate it. As far as we know at least.

rabeb25

HE of who can not be spoken of.

We aren't saying that we are the first people to ever use Sauergut, just that we are the first to use it in this setting AND have spreadsheet based calcs that incorporate it. As far as we know at least.

First known homebrewers in the states actively and solely using this for brewing acidification.

rabeb25

HE of who can not be spoken of.

The Brauwelt article is amazing. Had no idea that Beta amylase had such a short life.

The rather short half-life of β-amylase

at such temperatures (approx. 18.5 min at

62 °C and 9.3 min at 64 °C) brings about a

fairly rapid loss in its activity (fig. 2). By the

time the mash reaches 67 °C, there is prac-

tically no β-amylase activity. Thus, from

the standpoint of increasing the maltose

content of the wort, the rest at 67 °C can be

deemed largely superfluous.

Wow!

We have no shortage of amazing papers and technical documents on the site.

http://www.********************/uncategorized/list-of-brewing-references/

Kunze also touches on it in his book as well. Here is a graph from the chapter.

MSK_Chess

enthusiastic learner

We aren't saying that we are the first people to ever use Sauergut, just that we are the first to use it in this setting AND have spreadsheet based calcs that incorporate it. As far as we know at least.

lol, you guys are dedicated and produce very interesting articles and one must admire the dedication to your cause.

Guinness and probably many other breweries have been doing the same thing for decades as you are no doubt aware. I must admit that Guinness does have a certain 'tang' that is difficult to replicate at the home-brew level and I suspect as you mention in your article that this, 'grape', 'tang' you experience is German beers must be due to using sour wort. Its great that you have found a way to avoid using sulphites and documented your findings in a quantifiable way that we can replicate. I am going to try to make some sour wort for a brew. Normally I use acid malt. You must be very pleased with the results.

rabeb25

HE of who can not be spoken of.

Thank you for the kind words.

I heard a "rumor" Guinness does use soured wort AND is brewed low oxygen. No doubt we "lifted it" from the German brewing books, and what we do is nothing new. However we have tirelessly tried to scale and replicate it (all the methods) with our small brewing systems, and that I(we) will take credit for!

Cheers

I heard a "rumor" Guinness does use soured wort AND is brewed low oxygen. No doubt we "lifted it" from the German brewing books, and what we do is nothing new. However we have tirelessly tried to scale and replicate it (all the methods) with our small brewing systems, and that I(we) will take credit for!

Cheers

MSK_Chess

enthusiastic learner

Thank you for the kind words.

I heard a "rumor" Guinness does use soured wort AND is brewed low oxygen. No doubt we "lifted it" from the German brewing books, and what we do is nothing new. However we have tirelessly tried to scale and replicate it (all the methods) with our small brewing systems, and that I(we) will take credit for!

Cheers

Yeah they use it, you can taste it in their beer, or at very least their Extra Stout!

Sure thing, unless I am mistaken you do not mention the gravity of your pilsner mini mash? are you aiming for something like a yeast starter, 1030-1040? Also intrigued why you did not boil and cool it? Would that not have de oxygenated it?

A calculator to determine how much lactic acid in the form of live biological sour wort would be really helpful for both mash and sparge.

rabeb25

HE of who can not be spoken of.

Yeah they use it, you can taste it in their beer, or at very least their Extra Stout!

Sure thing, unless I am mistaken you do not mention the gravity of your pilsner mini mash? are you aiming for something like a yeast starter, 1030-1040? Also intrigued why you did not boil and cool it? Would that not have de oxygenated it?

My fault yes 10p (1.040). I utilize a mash out on all my beers which does the sterilization part. Boiling would work as well. These mashes were carried out low oxygen so basically the wort was oxygen free to start with.

Cheers

MSK_Chess

enthusiastic learner

excellent. how are we to determine how much sour wort to pitch into our mash tun and kettle. I would love if this became as easy as making a yeast starter.

rabeb25

HE of who can not be spoken of.

excellent. how are we to determine how much sour wort to pitch into our mash tun and kettle. I would love if this became as easy as making a yeast starter.

Oh it is just that easy. Titration is one way and guessing is another. If you are using freshly made sauergut made within a couple days of brewing I would use .8%-1.2%, and go from there. We have a spreadsheet that has all the calcs put in. If using Brunwater use lactic, and set the % to .8 and see how it does. If high just add more.

Cheers

The Brauwelt article is amazing. Had no idea that Beta amylase had such a short life.

The rather short half-life of β-amylase

at such temperatures (approx. 18.5 min at

62 °C and 9.3 min at 64 °C) brings about a

fairly rapid loss in its activity (fig. 2). By the

time the mash reaches 67 °C, there is prac-

tically no β-amylase activity. Thus, from

the standpoint of increasing the maltose

content of the wort, the rest at 67 °C can be

deemed largely superfluous.

Wow!

Interesting, I just wish I knew whether to believe Brauwelt's or Kunze's data. Kunze's chart implies a beta-amylase half life on the order of 60 minutes at 63°. Anyone got a way to resolve this huge discrepancy?

Brew on

MSK_Chess

enthusiastic learner

Interesting, I just wish I knew whether to believe Brauwelt's or Kunze's data. Kunze's chart implies a beta-amylase half life on the order of 60 minutes at 63°. Anyone got a way to resolve this huge discrepancy?

Brew on

Have you guys ever tried the 50/50 pseudo decoction mash that is advocated?

A more effective strategy for solving the

problem would be a mashing process ap-

proximating decoction during which the

kettle mash is not actually boiled (fig. 3).

After mashing-in approx. 50 percent of

the grist at 62 °C directly into the kettle,

it is heated to 72 °C and allowed to dextri-

nate, meaning that many α-glucan frag-

ments with reactive ends are formed. The

depolymerization of the starch is already

underway, which impedes subsequent ret-

rogradation, the reformation of quasi-crys-

talline structures when the starch cools to

below the gelatinization temperature. The

second half of the grist is mashed-in at

52 °C in the mash tun in order to preserve

the β-amylase. After dextrination in the

kettle, the two mashes are mixed together

in the mash tun to reach a temperature of

62 °C. The intense maltose formation in

the pre-digested substrate increases the

final attenuation to the desired level. The

procedure then continues according to the

high-short mashing process. The amount

of time required for the whole procedure

is no longer than the previously described

infusion process.

Sounds really interesting idea intended to preserve Beta amalyse for as long as is necessary and does not require boiling. Nor is it time consuming. I like this idea very much.

Big Monk

Trappist Please! 🍷

- Joined

- Dec 24, 2015

- Messages

- 2,192

- Reaction score

- 1,151

Interesting, I just wish I knew whether to believe Brauwelt's or Kunze's data. Kunze's chart implies a beta-amylase half life on the order of 60 minutes at 63°. Anyone got a way to resolve this huge discrepancy?

Brew on

I would think of the Kunze graph as more of a high level visual aid that shows you that peak β activity occurs at a much shorter time than generally accepted.

The Brauwelt graph has much more detail and has been verified in our Brewhouses.

Guinness and probably many other breweries have been doing the same thing for decades as you are no doubt aware. I must admit that Guinness does have a certain 'tang' that is difficult to replicate at the home-brew level and I suspect as you mention in your article that this, 'grape', 'tang' you experience is German beers must be due to using sour wort.

I don't believe that Guinness 'sours' their Guinness Flavor Extract. I believe that its flavor is due to the fact that they steep their Roast Barley in their water (which is almost distilled water) and that produces a pH of around 4.5 for the extract. That is added back to the wort from the pale malt and barley mash.

I find the twang is the combination of roast and low pH, not lactate ions. However, if you have evidence or knowledge that they do allow the extract to sour prior to use, I welcome it.

MSK_Chess

enthusiastic learner

I don't believe that Guinness 'sours' their Guinness Flavor Extract. I believe that its flavor is due to the fact that they steep their Roast Barley in their water (which is almost distilled water) and that produces a pH of around 4.5 for the extract. That is added back to the wort from the pale malt and barley mash.

I find the twang is the combination of roast and low pH, not lactate ions. However, if you have evidence or knowledge that they do allow the extract to sour prior to use, I welcome it.

Gee I dunno Martin. It could be that the taste that we perceive as 'tang', is the result of steeping roasted malts although I doubt this is the same thing as the 'tang' achieved from lactic acid (although I am willing to be corrected) Naturally I have no empirical evidence. However I am willing to give credence to the idea that the 'tang' is from lactic acid, whether soured wort or food grade lactic acid. Can this same 'tang' be achieved from cold steeping roast malts? It is known that they do cold steep the roast malts, so maybe it is.

Btw how can we incorporate a soured wort into bru'n'water calculations?

I'm sure it was someone from beoir who said there were plenty of containers of lactic acid in their brewery when they went to visit, but I can't find that source. There is a bit in this where one of their brewers doesn't rule it out, but it's not really surprising that they would keep quiet about these things, rightly or wrongly

http://allaboutbeer.com/guinness-stout-decline/

fwiw I get a lactic taste from FES, less so in their other offerings

And cheers to the OP, the mash profile is indeed very interesting . Plus the rest of lodo is too

http://allaboutbeer.com/guinness-stout-decline/

fwiw I get a lactic taste from FES, less so in their other offerings

And cheers to the OP, the mash profile is indeed very interesting . Plus the rest of lodo is too

Cavpilot2000

Well-Known Member

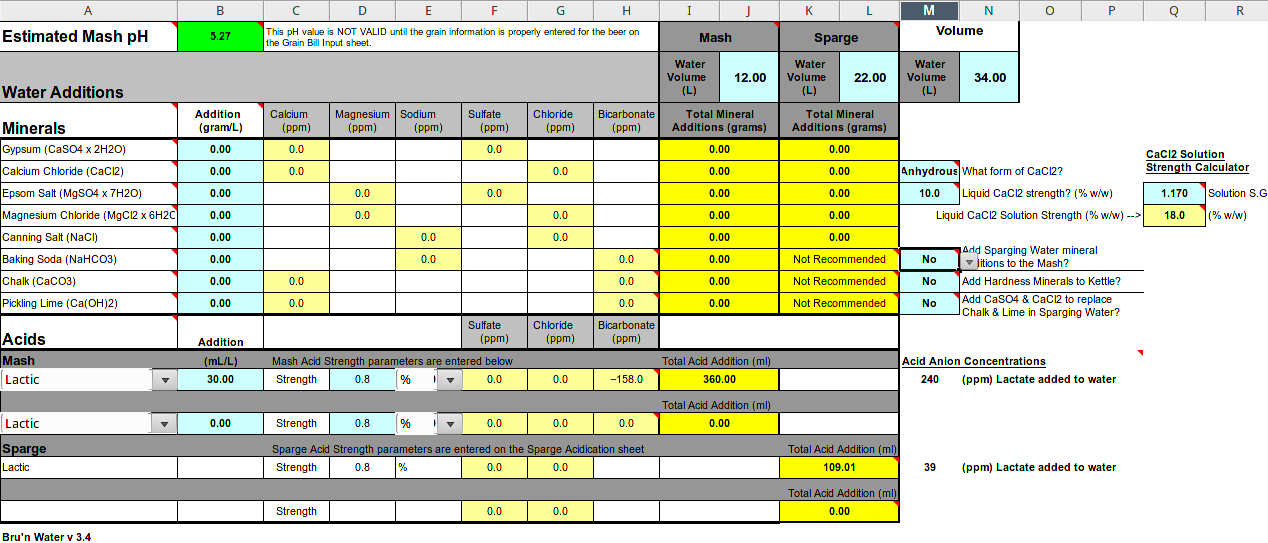

Btw how can we incorporate a soured wort into bru'n'water calculations?

I use BruNWater, and am involved in the Low O2 community (not one of the main contributors, just one of the guys enjoying the view from the shoulders of giants) so I can speak to this:

You enter it as lactic acid, but instead of the common 88% acid, you enter the percentage that your sour wort has. Titration will tell you that percentage (it's not as complicated as it sounds once you do it once or twice), or you can just estimate initially and adjust based on results. If estimating, as Bryan said earlier, new sauergut (a few days old) will be anywhere from 0.8% to 1.2%. If you maintain a reactor, it will increase over time. Some of the guys' sauergut is consistently around 1.75%.

So, whereas if using technical lactic acid, BruNWater might tell you to add just a few ml, a sauergut addition might be 500ml or more (the difference between using an 88% concentrated acid vs. a 1.2% acid).

Hope this helps. I did a one-off batch of sauergut and it was pretty easy, but I am setting up a dedicated "reactor" just so I don't have to make it every time.

MSK_Chess

enthusiastic learner

I'm sure it was someone from beoir who said there were plenty of containers of lactic acid in their brewery when they went to visit, but I can't find that source. There is a bit in this where one of their brewers doesn't rule it out, but it's not really surprising that they would keep quiet about these things, rightly or wrongly

http://allaboutbeer.com/guinness-stout-decline/

fwiw I get a lactic taste from FES, less so in their other offerings

And cheers to the OP, the mash profile is indeed very interesting . Plus the rest of lodo is too

Super interesting article.

When asked about lactic acid, he became almost frosty, choosing his words with the care of a Soviet diplomat: Theres a number of elements we dont talk about, as Im sure youll understand. One change he was happy to discuss was the reduction in dissolved oxygen in the beer over the last 20 years: Dissolved oxygen is a total no-no, it imparts off flavors. If you drank a beer with dissolved oxygen in high concentration youd say, its off, its not right.

I found a quotation from an article entitled, Guinness secrets revealed.

Key finding #1 Guinness does use a sour blend for their stout

No ratios or processes were described, but the brewers did cop to the fact that part of the key feature of Guinness Stout was a sharp acidity contributed by lactic acid.

https://www.fivebladesbrewing.com/guinness-secrets-revealed/

rabeb25

HE of who can not be spoken of.

Super interesting article.

Dissolved oxygen is a total no-no, it imparts off flavors. If you drank a beer with dissolved oxygen in high concentration youd say, its off, its not right.

I have said that a few thousand times!

pricelessbrewing

Brewer's Friend Software Manager

Just to nitpick, mashout and boiling doesn't truly sterilize, as there are bacteria and spores that will survive boiling temps just fine.My fault yes 10p (1.040). I utilize a mash out on all my beers which does the sterilization part. Boiling would work as well. These mashes were carried out low oxygen so basically the wort was oxygen free to start with.

Cheers

MSK_Chess

enthusiastic learner

I use BruNWater, and am involved in the Low O2 community (not one of the main contributors, just one of the guys enjoying the view from the shoulders of giants) so I can speak to this:

You enter it as lactic acid, but instead of the common 88% acid, you enter the percentage that your sour wort has. Titration will tell you that percentage (it's not as complicated as it sounds once you do it once or twice), or you can just estimate initially and adjust based on results. If estimating, as Bryan said earlier, new sauergut (a few days old) will be anywhere from 0.8% to 1.2%. If you maintain a reactor, it will increase over time. Some of the guys' sauergut is consistently around 1.75%.

So, whereas if using technical lactic acid, BruNWater might tell you to add just a few ml, a sauergut addition might be 500ml or more (the difference between using an 88% concentrated acid vs. a 1.2% acid).

Hope this helps. I did a one-off batch of sauergut and it was pretty easy, but I am setting up a dedicated "reactor" just so I don't have to make it every time.

Brill. If we assume a value of 0.8 would something like this below sound reasonable. Bru'n'water on the Pilsen setting (which is quite close to my own tap water) is suggesting 360ml of sour wort for the mash and 109ml for the sparge.

MSK_Chess

enthusiastic learner

Could we use 47g of DME to make a 470ml sour wort starter aiming for 1040? That being the case how much grain would we need to add this?

dyqik

Well-Known Member

Btw how can we incorporate a soured wort into bru'n'water calculations?

Actually, I'm also interested in including largish Campden/KMeta/NaMeta additions in bru'n'water.

BTW, I notice that some of LoDO updates seem to be do with reducing the amount of KMeta/NaMeta required, and that that seems to be driven by achieving low mineral content for e.g. BoPils or similar. I guess that for e.g. NEIPA, where we are also very concerned about DO, but not about low minerality (we want maybe ~100-200ppm SO4), then we could just keep using large Campden additions (as long as the sulfites end up as sulfates)? I've not read too far into the details though.

Big Monk

Trappist Please! 🍷

- Joined

- Dec 24, 2015

- Messages

- 2,192

- Reaction score

- 1,151

Could we use 47g of DME to make a 470ml sour wort starter aiming for 1040? That being the case how much grain would we need to add this?

You really want to be using fresh wort made from grains, preferably made by limiting Oxygen. Low Oxygen goes for the Sauergut too! Remember, you'll be putting a fairly large dose of this into your wort when acidifying.

rabeb25

HE of who can not be spoken of.

Could we use 47g of DME to make a 470ml sour wort starter aiming for 1040? That being the case how much grain would we need to add this?

Sure you could. I dunno a handful or so.

However not be dismissed the the flavor of low oxygen wort, and this really comes into play here. The brewers utilizing this method, are going to maintain a reactor. That reactor is filled with diluted first runnings at a rate of 50/50 going in to recharge the reactor. In the case of the Large macros this is going to be low oxygen wort, which is literally like liquid grain flavor. Some breweries are using knockout additions (10 minutes) and that is where the sauergut shines, you just made an addition of fresh wort to the kettle preserving much of the fresh low oxygen wort qualities. Weheinstephaner for instance does this and you can pick up the fresh wort like flavors in the beers.

That being said, I would just make an extra qt or 2 on your next brew session and snatch the wort preboil, sour and move on. If you have to make it I will always suggest a low oxygen minimash. But I know folks on our forum who have used DME. Not sure on the outcome though.

Cheers

rabeb25

HE of who can not be spoken of.

Actually, I'm also interested in including largish Campden/KMeta/NaMeta additions in bru'n'water.

BTW, I notice that some of LoDO updates seem to be do with reducing the amount of KMeta/NaMeta required, and that that seems to be driven by achieving low mineral content for e.g. BoPils or similar. I guess that for e.g. NEIPA, where we are also very concerned about DO, but not about low minerality (we want maybe ~100-200ppm SO4), then we could just keep using large Campden additions (as long as the sulfites end up as sulfates)? I've not read too far into the details though.

Actually the driving factor is sulfites and sulfur. The goal here is less is more, this is not style dependent, though lager yeasts tolerate a lot more.. The sulfites have always been a crude(albeit brilliant) hack to achieve this on our scale.

Ale yeasts HATE residual sulfites and sulfur and in turn spit it back into your beer. Hundreds and Hundreds of batches have been brewed and this is what we have found. I would always suggest not getting your minerals from the sulfite dose. Make the modifications to your processes and augment short comings with the sulfites. Folks get in trouble the other way around.

Cheers

dyqik

Well-Known Member

Actually the driving factor is sulfites and sulfur. The goal here is less is more, this is not style dependent, though lager yeasts tolerate a lot more.. The sulfites have always been a crude(albeit brilliant) hack to achieve this on our scale.

Ale yeasts HATE residual sulfites and sulfur and in turn spit it back into your beer. Hundreds and Hundreds of batches have been brewed and this is what we have found. I would always suggest not getting your minerals from the sulfite dose. Make the modifications to your processes and augment short comings with the sulfites. Folks get in trouble the other way around.

Ah, OK. I know some yeasts will throw off hydrogen sulfide (it's the lovely smell of e.g. Harveys of Lewes's fermenters and casks), and I assume that could be easier for them if sulfites are present, maybe more so than sulfates?

Although the opposite seems to be true in wine yeasts: e.g. see https://www.practicalwinery.com/novdec05/novdec05p26.htm

stickyfinger

Well-Known Member

The Brauwelt article is amazing. Had no idea that Beta amylase had such a short life.

The rather short half-life of β-amylase

at such temperatures (approx. 18.5 min at

62 °C and 9.3 min at 64 °C) brings about a

fairly rapid loss in its activity (fig. 2). By the

time the mash reaches 67 °C, there is prac-

tically no β-amylase activity. Thus, from

the standpoint of increasing the maltose

content of the wort, the rest at 67 °C can be

deemed largely superfluous.

Wow!

I'd like to see some more data on that. I can't believe that. I have done mashes at 73c, and they keep converting beyond 10 minutes.

rabeb25

HE of who can not be spoken of.

I'd like to see some more data on that. I can't believe that. I have done mashes at 73c, and they keep converting beyond 10 minutes.

That would be alpha's territory, your beta is LONG gone by then.

Brauwelt is one of if not the THE most respected professional brewing journals. I highly doubt they lead folks astray!

stickyfinger

Well-Known Member

That would be alpha's territory, your beta is LONG gone by then.

Brauwelt is one of if not the THE most respected professional brewing journals. I highly doubt they lead folks astray!

maybe my mashes are converting in 10 minutes then, and the rest of the time alpha is just increasing unfermentable sugars. seems hard to believe.

rabeb25

HE of who can not be spoken of.

maybe my mashes are converting in 10 minutes then, and the rest of the time alpha is just increasing unfermentable sugars. seems hard to believe.

Most modern malts convert in 10-15 minutes at that high of a temp. Your malt analysis sheets have this figure.

Most modern malts convert in 10-15 minutes at that high of a temp. Your malt analysis sheets have this figure.

Could you post an example of a malt data sheet that shows this kind of information? In general, I find malt data sheets hard to come by (maybe some maltsters make sheets more readily available, and I'm just using the ones that don't), and I've never seen any kind of conversion rate information. Nor have any of the articles I've read on interpreting malt data sheets talked about conversion rate information on the sheets.

Brew on

rabeb25

HE of who can not be spoken of.

Could you post an example of a malt data sheet that shows this kind of information? In general, I find malt data sheets hard to come by (maybe some maltsters make sheets more readily available, and I'm just using the ones that don't), and I've never seen any kind of conversion rate information. Nor have any of the articles I've read on interpreting malt data sheets talked about conversion rate information on the sheets.

Brew on

Sure all Weyermann (the only malt I use) comes with complete details so I can't speak to others... Here are a few.

http://analyses.weyermann.de/R205-001360-01.pdf

http://analyses.weyermann.de/q230-003360-01.pdf

It's under saccrification time. That is the time it takes @70C to obtain iodine normality.

stickyfinger

Well-Known Member

Sure all Weyermann (the only malt I use) comes with complete details so I can't speak to others... Here are a few.

http://analyses.weyermann.de/R205-001360-01.pdf

http://analyses.weyermann.de/q230-003360-01.pdf

It's under saccrification time. That is the time it takes @70C to obtain iodine normality.

might be for unrealistic mash conditions, such as floured malt

Big Monk

Trappist Please! 🍷

- Joined

- Dec 24, 2015

- Messages

- 2,192

- Reaction score

- 1,151

might be for unrealistic mash conditions, such as floured malt

The important thing to remember is that β rest duration does NOT have to be longer than 25-35 minutes for someone with step mashing capability.

Remember that single infusion mashing is a compromise. You pick a temperature that hovers in the ideal β rest ranges and you hold it for longer times to compensate for the fact that the typical β rest temperature (148-149 °F) shows less activity due to β amylase degradation as temperature increases.

You can confirm the speed at which conversion occurs by observing wort clarity through a sight glass. For a typical 2 β rest regimen, you'll see pronounced wort clarity by the end of the 2nd β rest (25-35 minutes).

Similar threads

- Replies

- 1

- Views

- 506