Provocative title, but what I'm really asking, is:

Is there a such thing as too little oxygen? Once the yeast use up the O2, they'll start fermenting and stop reproduction. So it seems like less O2 would only lead to less yeast, a longer fermentation time, less trub/lees, but the same beer at the end (but maybe less waste, since there's less gunk to deal with when racking).

Anyway, oxygenation has been the thing I sweat least, just fill the bucket through my grain strainer, once I'm at about 3 gals, plug the hole, and give it a few hard shakes, and top it off. Always comes out fine.

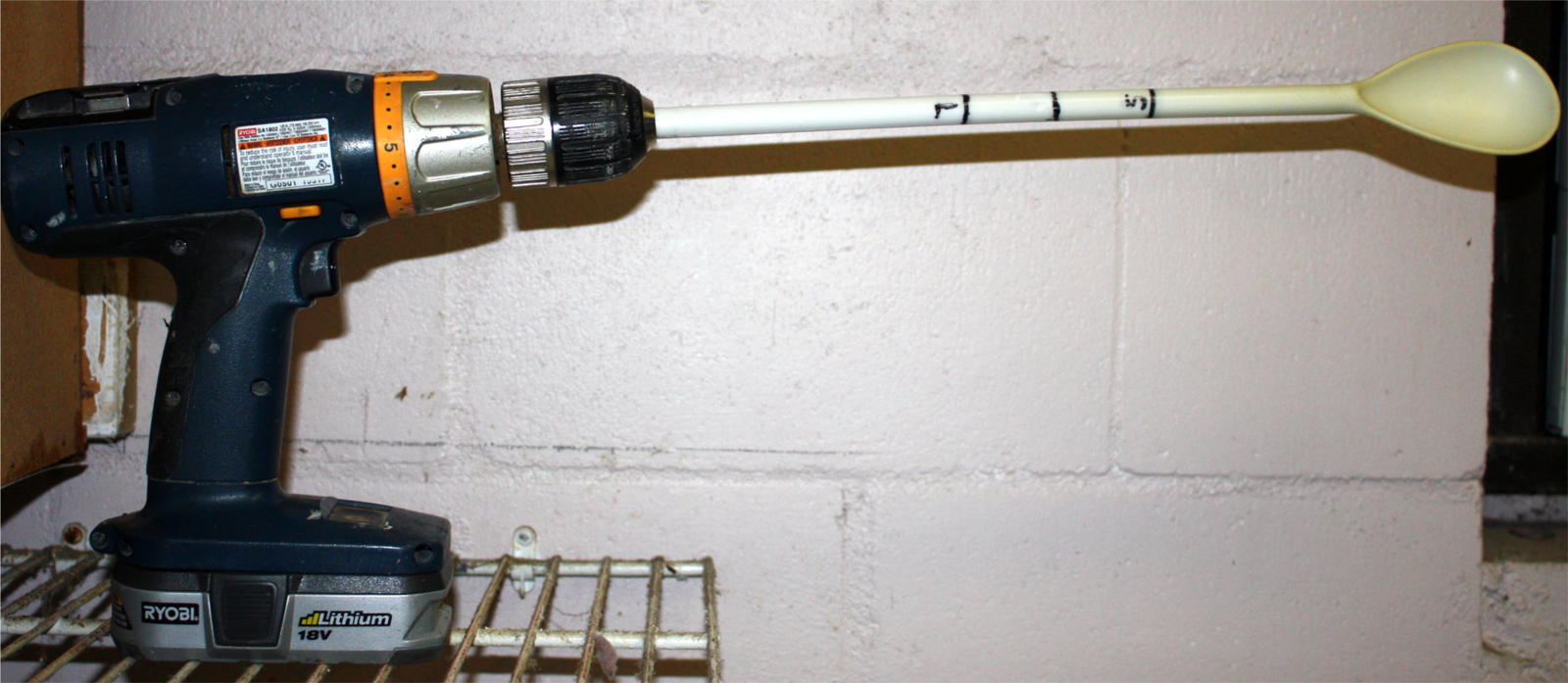

I notice people sell oxygenator kits though, which in addition to being CRAZY dangerous, again, seems unnecessary and expensive. Anyone want to enlighten me?

Is there a such thing as too little oxygen? Once the yeast use up the O2, they'll start fermenting and stop reproduction. So it seems like less O2 would only lead to less yeast, a longer fermentation time, less trub/lees, but the same beer at the end (but maybe less waste, since there's less gunk to deal with when racking).

Anyway, oxygenation has been the thing I sweat least, just fill the bucket through my grain strainer, once I'm at about 3 gals, plug the hole, and give it a few hard shakes, and top it off. Always comes out fine.

I notice people sell oxygenator kits though, which in addition to being CRAZY dangerous, again, seems unnecessary and expensive. Anyone want to enlighten me?