Here is a brief description of the very traditional and very old practice of making nuruk. Note that this is essentially the same steps as the farmhouse practice of making soybean cakes from cooked soybeans (the pressed wrapped cakes are called Meju in Korea) and then wrapping the cakes in rice straw and suspending them from the farmhouse rafters to slowly mold and dry out for later use in making soy sauce and miso pastes. Different substrates and somewhat different microorganisms but the same basic practice for both soy sauce and makgeolli. From the sci lit reference posted by the OP, it strongly appears that Korean nuruk sold for household use is still made the traditional way as the composition of microflora is highly variable. The commercial makgeolli sold in plastic bottles is another story and appears to be a highly manipulated fermentation and many commercial makgeolli makers include aspartame as a non-nutritive sweetener that will not be consumed by the still active cultures. Plus they are free to add artificial flavors and color. There are still traditional makgeolli makers who make their own nuruk on site and ferment the makgeolli using all traditional methods and ingredients.

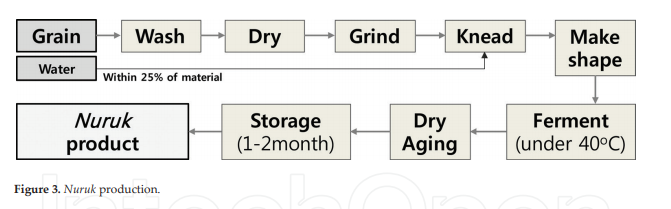

Nuruk is made from wheat or barley that is coarsely ground although I have heard of a green bean nuruk that may or may not be made of soybeans or asian long beans. The ground wheat is then wet and tightly packed into molds to make a hard cake. In the past people would stomp on the wheat to make it compact and while some brewers still use this method most nuruk producers will mechanically compress the nuruk into cakes. The nuruk is then wrapped in straw and allowed to incubate for about a week. This allows yeasts and molds from the environment to proliferate throughout the wheat cake. Next, the nuruk is dried in the sun and broken up for use in the brewing process.

The use of wheat or rice straw to hold in moisture and provide a rich source of spores is likely very important to the final quality of the nuruk as most all of the traditional solid alkaline ferments start by wrapping the cooked starch pastes with a thick layer of straw and that straw provides a rich source of spores to actively ferment the starch paste. Note this fermentation is generally slow and aerobic in nature while the secondary liquid fermentation is much more anaerobic, although the unglazed pottery Onggi if used are claimed to breath compared to plastic or metal fermentation vessels. Fermenting makgeolli in traditional Onggi unglazed pottery is not widely performed today but would make for a pirized batch and beautiful presentation.

The OP posted a link to a research article with some very valuable info on just what is to be found inside your nuruk. The reserachers analyzed 42 samples of nuruk from various regions of Korea provinces and were not able to ascertain a regional variability in the microflora. Also important to note that a significant portion, 13 out of 42 nuruk, contained foodborne pathogens such as B. cereus or Cronobacter sakazakii. It appears that these pathogenic bacteria do not grow in the glutinous rice culture media or the rice wine would make you very sick when consumed.

That right there tells you that most nuruk sold to households are being prepared using an traditional approach (at least two thousand years of rice wine making history and probably closer to 9 thousand year tradition of rice wine making in China). They are not inoculating with pure cultures as no business would inculate with such a wide range of variable "pure cultures" as a business practice. To continue with their findings:

There were various species of lactic acid bacteria such as Enterococcus faecium and Pediococcus pentosaceus in nuruk. It was unexpectedly found that only 13 among the 42 nuruk samples contained Aspergillus oryzae, the representative saccharifying fungi in makgeolli, whereas a fungi Lichtheimia corymbifera was widely distributed in nuruk. It was also found that Pichia jadinii was the predominant yeast strain in most nuruk, but the representative alcohol fermentation strain, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, was isolated from only 18 out of the 42 nuruk. These results suggested that a variety of species of fungi and yeast were distributed in nuruk and involved in the fermentation of makgeolli. In this study, a total of 64 bacterial species, 39 fugal species, and 15 yeast species were identified from nuruk. Among these strains, 37 bacterial species, 20 fungal species, and 8 yeast species were distributed less than 0.1%.

One very important concept when comparing pure culture isolates to "wild culture technique" is the concept of natural succession. In natural winemaking, natural yeast are not inoculated by pitching a pure culture into the grape must before fermentation. By utilizing the natural microflora on the grape skins and stems a certain amount of wild yeast and bacteria are already present to start the fermentation. If you follow along by trying to identify the dominant cultures as the fermentation progresses, the dominant yeast at the end of the fermentation is always S cerevisiae. But this yeast is usually not identifiable in sufficient numbers at early time points as it is not the first or fastest out of the starting block. Many different yeast and bacteria can come along to dominate at early fermentation time points until the alcohol and acid levels increase to the point where only S. cerevisiae can survive. So both the pure culture method of pitching S. cerevisiae and the natural methods have the same endpoint with S. cerevisiae dominating but only one method actually includes pitching pure culture of the yeast strain. It is claimed by the natural winemaking crowd that the intermediate strains contribute flavors and aromas that add complexity to the final wine and basically the same claims would be made by the proponents of using natural nuruk to make makgeolli. Of course you do run the risk of a failed batch of expensive wine, so most large scale wine makers do not employ such methods today as the risk to reward is not great enough to risk a spoiled batch of expensive wine. Smaller producers do employ such methods and many do find customers willing to pay more for such traditional winemaking. Much the same can be said for traditional Sake makers and Korean makgeolli merchants.

In the case of nuruk, the yeasts and bacteria present at levels of only 0.1% in the wheat cake may become dominant in the final rice wine as they find the medium to be much more conducive to growth than the dry wheat cake under warm aerobic conditions. The aerobic fungi will contribute exocellular enzymes like starch amylase but will not grow at all in the cooked rice medium as it quickly becomes anaerobic with the rapid CO2 evolution pushing out all the available oxygen. Those are growth conditions that certain yeast and LAB will thrive in.

Another important factor is feeding makgeolli with multiple rounds of cooked glutinous rice after fermentation has really taken off. You start with one nuruk cake and proceed to add batches of cooked glutinous rice after each peak in fermentation has occured. This first addition is called mitsool and all subsequent stages are known as dotsools. Depending on your recipe you have any where from one to four (sometimes even more) dotsools. In each one of these stages, the initial wild microflora found on the nuruk cake is forced to adapt to the increasing amounts of ethyl alcohol and lower pH created by LAB. This is what makes the process sanitary and clean. It's like the multiple feedings in maintaining a sourdough culture and keeps the culture strong and in log growth phase.

In the mitsool stage you will add rice, water, and nuruk. Main thing to note is that the rice you add at this stage will be ground rice prepared using a wide variety of techniques. When you grind and cook the rice you are allowing the amylose and amylopectin in the rice to break down into simple sugars that yeasts can easily consume and convert into alcohol. You want to produce a lot of alcohol at the start of the brewing process. This increase in alcohol, along with a reduction in pH by other bacteria, will help prevent any contamination in your brew.

After a few days you can add more rice and sometimes water (it depends on the recipe) and at this step you have made a dotsool. A brew that had one mitsool and one dotsool is called an eeyangju, or a two stage recipe. If two dotsools are made then it is a samyangju, three stage recipe. Usually, recipes don’t go beyond three stages however there is one popular cheongju called Cheonbihyang that uses a five stage, oyangju, recipe. There is even a recipe that has up to twelve stages.

The rice that is added can either be steamed rice or ground rice. Adding rice that has been ground and cooked will give the yeast more simple sugars to keep making alcohol. Steamed rice is only added to the last dotsool. At this point you don’t need to make more alcohol you just need to break down the amylose and amylopectin in the rice with enzymes produced by fungi. This slow breakdown of starches to sugars will add sweetness to the final product. This process takes time and a good brew isn’t filtered until a few weeks after the last dotsool is added.

Also one thing I didn’t mention about mitsool is that if you stop there the brew is called a dangyangju. However only certain recipes are danyangjus and they risk contamination if not done right. A samyangju is a really great brew to master. It’s not too long, there is less risk of contamination, and it gives reliable results.

![Craft A Brew - Safale S-04 Dry Yeast - Fermentis - English Ale Dry Yeast - For English and American Ales and Hard Apple Ciders - Ingredients for Home Brewing - Beer Making Supplies - [1 Pack]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/41fVGNh6JfL._SL500_.jpg)