Thanks for the great summary.Ah - so many points to address.

But just to get the big one out of the way - Ordinary Bitter is like American football. The locals just call it "football", but to anyone from the civilised world who is looking to classify it among the wider family, it gets called American football. And even the BJCP now call it "Standard/Ordinary Bitter" - standard bitter is the more common phrase in the trade here, but punters always call it just bitter. Young's is an exception - Ordinary in their case was almost a brand name, like Fuller's having ESB.

And we just know what bitter looks like, it doesn't need to be spelled out on a label. Technically Budweiser is a lagerbier, maybe even a Pilsner lagerbier - but in the US it is just "beer". It's sort of like that.

And they are damned difficult to do well, truly one of the hardest styles to brew, in fact I know enough not to have even tried to make one, I'm just not that good a brewer. Whilst I'm not quite asancientexperienced as CC, I do have several decades of drinking bitters of all kinds, mostly on cask in a pub - and before Covid knackered my senses I have judged local stages of the Champion Beer of Britain.

What I would say is that something happens once a bitter gets above about 4.2% and they just work a lot better, there's enough mouthfeel to balance everything else - and balance is everything in these beers, it's about balancing all the ingredients from hops to carbonation to malt to minerals. That's how you get the sessionability, that keeps people in the pub and keeps the tills ringing.

So if people are new to British beers, I always suggest they start with a best in the 4.2-4.5% range, things just taste better there. Outside city centres pubs generally either have either a loose or explicit limit of 4.5% on cask beer as above that it usually doesn't get the turnover you need for cask. And if your best is in that range then 3.8% is a reasonable place for the ordinary to be - you'll find that's where the decent breweries tend to end up, whereas the ones below that are driven more by accountants than beer lovers. The latest vandalism has come from the taxman increasing the ABV of his low strength duty rate to anything below 3.5%. Previously it was less than 2.8% which was so low the big boys knew it wasn't worth chasing. Whereas <3.5% is close enough that it's very tempting to save £millions by nudging their ordinary bitters down from 3.7 or 3.8%, but it's going to be the death of classic bitter as they all taste like pish.

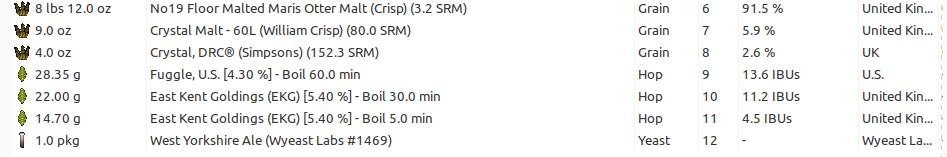

Anyway, if you're stuck with 8A then my tip for impressing the guys at the brew club would be - make it as close to a best as you can. So you definitely want to be up at the 3.8-3.9% end of things (personally I would say 4% is the dividing line between standard and best), mash high, maybe even sneak a little dextrin malt or similar in there for more body. Use the best malt you can, ideally floor-malted, ideally Otter or Promise. Personally I probably wouldn't use sugar - why thin it out when you're fighting for body?

There's a bit of a decision to whether you're going for more of a northern or southern style. Growing up in the Blessed Lands I acquired a taste for beer with less crystal, often around 7% torrefied wheat and more bitterness - but probably around BU:GU 0.85 is my ideal for something in bottle, anything higher is really designed to be served through a sparkler.

Whereas in the Degenerate Wilds you generally find more crystal (Fuller's use 7.2% light crystal in their partigyle, I wouldn't go much more than that) sometimes a bit of maize, and bitterness of 0.7-0.75-ish.

100ppm calcium is an absolute minimum for any British beer, you need it for cask beer to get the yeast to drop out. Play around with Cl:SO4 ratios to see what you like, somewhere around 120:180 is a good starting point but I wouldn't get too hung up on it, it's a very personal thing.

For your first one, the cost of hops is marginal so instead of a more authentic "cheap rubbish from Eastern Europe" just go with the best, EKG. In future you can play with Challenger or First Gold, maybe you will find one of them more to your taste, but just go with the classic for now. Everyone likes Goldings, not everyone like Fuggles. Oh, and vintage variation is a big thing in English hops, far more so than almost any other hopgrowing region.

Another not-quite-authentic cheat is just to be generous with the hops and spread them around, some in the whirlpool, some dry hop.

Yeast - use the most characterful you can, so not Lallemand London! If you're not going the authentic route of harvesting or buying Brewlab then 1469 is probably the best bet of the US lab yeasts, maybe Imperial Pub if you want the Fuller's orange thing (forget WLP002 and 1968). I must admit I have quite a soft spot for WLP041 Pacific Ale - it's not flashy, but it just produces a really drinkable pint.

People tend to underestimate the carbonation of British beers, unless they've been squirted in the face whilst tapping a cask! And you seem to lose a bit in bottle, for me targeting about 1.7-1.8vol is about right - but you don't want to overcarbonate, it's all part of the balance. And of course don't serve too cold, it wants to be cellar temperature, somewhere around 50-55F. And do give it a bit of time to mature, it takes time for everything to knit together.

I'd really like to know your opinion about turning dry yeast into liquid yeast and its benefits.

As posted earlier in this thread, I've brewed a bitter with 3g of s04, that I multiplied in a 2l starter. So I basically made sure that the majority of the pitch was not from the dried generation of the yeast.

From my limited point of view, this technique improved the yeast. The resulting beer tastes like a great bitter. Clean but still English. I don't know if I would have had the same beer without this "reawakening" of the yeast.

Have you tried this? What are your thoughts on this?

![Craft A Brew - Safale BE-256 Yeast - Fermentis - Belgian Ale Dry Yeast - For Belgian & Strong Ales - Ingredients for Home Brewing - Beer Making Supplies - [3 Pack]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/51bcKEwQmWL._SL500_.jpg)

.

.