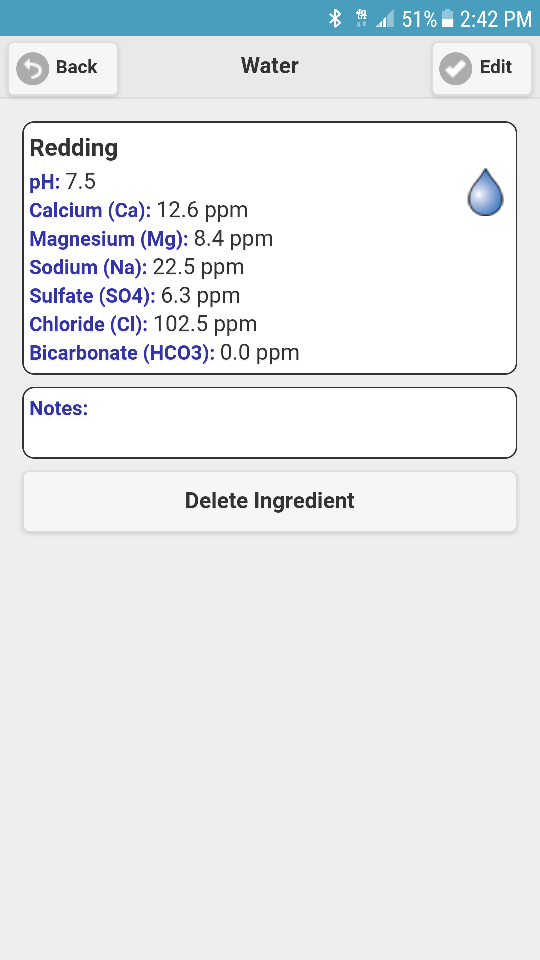

There is something radically wrong with that water report.

It is pretty clear that they slipped the decimal point one place to the right in the chloride as 10.2 is a reasonable average given the extreme values. Other than that it seems OK.

The reason why your water report doesn't ion balance is most likely that it is an average of samples grabbed throughout the year.

The reason it doesn't balance is because you are all looking at the numbers with decimal places attached to them and assuming that they came from AAS or ICP (a reasonable assumption but note that the alkalinity numbers have decimal values too) and are thus inserting the values into your calculations as ppm as the metal. In fact they are evidently ppm as CaCO3 and inserting them as such (and using 10.25 for the chloride) gives a much better balance but still not a perfect one.

So why not. If you have a bunch of water ion profiles each of which balances and you average each ion's concentration and then sum the averages you will still get balance. So clearly the reported data don't come from taking the averages from an ensemble of water profiles each of which balances. In the first place, no water profile will balance perfectly. In the second place, they don't do a complete profile each time they do a test. Some parameters are measured much more frequently than others. For example, alkalinity was measured "1-16 - 12-16" whatever that means (once in January and once in December of 1916 or 12 times on the 16th of the month?) whereas sulfate was measured 9 - 16. We would expect a profile made up of measurements collected on different days to balance and I believe that's the case here (once you understand what the numbers represent).

On to the philosophical question "Should I take profiles seriously?" I think the answer is "somewhat seriously" but not too seriously. First thing to do is to ask yourself "What is my goal?" and the obvious answer is "To make the best Rongovian Summer Ale possible!" The difficulty here is that we have to define what "best" means before we can proceed. Put in other words, we need to have an optimality criterion. If that criterion is authenticity (matching a traditional style) then profiles are a lot more important than if optimality means producing a beer that sells well or producing a beer that you like or producing a beer that your friends rave about or winning in a competition. Assuming authenticity is the goal then you need to at least consider the published profiles but be careful with them. You will find that lots of them contain appreciable amounts of bicarbonate. This is often there because the creator of the profile thought the style should have a high level of calcium, magnesium and/or sodium but wanted to limit the sulfate and chloride to less than the amount necessary to balance the metals at reasonable pH. What do do? Toss in bicarbonate and this is what some of them do. Of course as the charge on bicarbonate changes with pH the profile only balances at one pH (8.3). If the water of the city you are trying to duplicate has pH of 7.2 then the published profile isn't going to work. If you see a profile that contains bicarbonate be very wary.

If an enjoyable beer is the goal at least look at the stylistic ions (sulfate, chloride, sodium, potassium) to get a general idea as to how much of those ions characterize the beer. Better still, research the style to find out what kind of water the original brewers of it had to deal with and set the stylistic ions at appropriate levels. Keep in mind that as the body responds to the logarithm of sound intensity, light intensity it probably responds logarithmically to taste stimuli as well so that if you change an ion concentration by less than about 3 dB (doubling or halving) you probably aren't going to notice much difference. I should note that this is a theory of mine which I have only anecdotal tasting evidence for. I also note that there is a threshold effect. Doubling (increasing) chloride from 1 to 2 mg/L isn't going to make much of a difference in perceived beer quality but doubling it from 10 to 20 or 20 to 40 probably will. The message is that if you decide you want 150 ppm of sulfate and can only get a number that is withing say ± 20 ppm of that, don't worry about it.

I often advocate starting out with nothing but some calcium and chloride. Brew with just those and then taste the finished beer with additions of small amounts of calcium sulfate in the glass. This will tell you if sulfate improves or degrades the quality in the taters' opinions. If you know you like sulfate you can start with a modest amount of that but in any event you are going to have to experiment to find the sweet spot. No spreadsheet, calculator, book or magazine article can tell you how to brew the best beer.

Final note: the bicarbonate content of this water is not 0. Based on the reported alkalinity and pH it would be 42.2 mg/L. The reason that it is not reported is because it is difficult to measure and no one cares about it (except the spreadsheet authors who use it as a proxy for alkalinity thus confusing so many). The lab measures alkalinity because it is a simple test. It is then up to you to calculate bicarbonate if you care about it. Or rely on Ward Labs calculation (which is a little off).

![Craft A Brew - Safale BE-256 Yeast - Fermentis - Belgian Ale Dry Yeast - For Belgian & Strong Ales - Ingredients for Home Brewing - Beer Making Supplies - [3 Pack]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/51bcKEwQmWL._SL500_.jpg)