Velnerj

Simul justus et potator

I have read many posts on this forum about using "cold" (read room temp) water for sparging. The overwhelming anecdotal evidence seems to point to the fact that using cold water brings the same efficiency as using hot water. The only difference being is that it takes a bit longer to reach a boil afterwards.

I don't doubt my brewing brother and sister's experience. And this is not a post that disagrees with those results. But rather I would like an intermediate level science explanation of why this works.

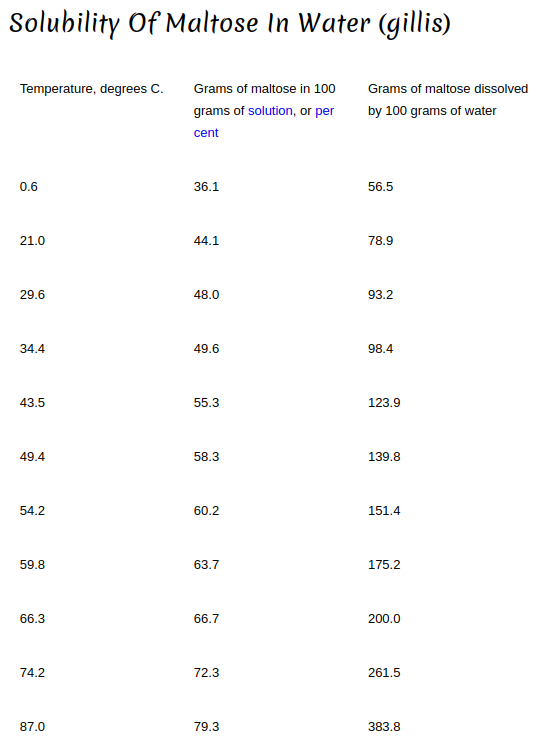

In my mind temperature and water solubility are connected (especially with solids in liquid). The hotter the liquid (to a point) the faster and the more the solids will dissolve.

If I have a cup of cold water and add 4 table spoons of sugar to it, many of the granules will collect at the bottom even after a good amount of stirring. On the other hand, if that water is hot, the sugar dissolves very quickly and no visible granules collect at the bottom. Not only does the hot water work faster but it is able to hold more sugar than the cold water.

I figured the same would be applied to a sparge. The hot sparge water would dissolve the sugars quicker and be able to hold more sugars than cold sparge water.

But this isn't being reported. Is it that the temperature difference between room temp (25C?)and sparge water (70C?) isn't enough to make a difference? Or the amount of contact time isn't enough to make a difference? Why are the results the same regardless of sparge water temperature?

I don't doubt my brewing brother and sister's experience. And this is not a post that disagrees with those results. But rather I would like an intermediate level science explanation of why this works.

In my mind temperature and water solubility are connected (especially with solids in liquid). The hotter the liquid (to a point) the faster and the more the solids will dissolve.

If I have a cup of cold water and add 4 table spoons of sugar to it, many of the granules will collect at the bottom even after a good amount of stirring. On the other hand, if that water is hot, the sugar dissolves very quickly and no visible granules collect at the bottom. Not only does the hot water work faster but it is able to hold more sugar than the cold water.

I figured the same would be applied to a sparge. The hot sparge water would dissolve the sugars quicker and be able to hold more sugars than cold sparge water.

But this isn't being reported. Is it that the temperature difference between room temp (25C?)and sparge water (70C?) isn't enough to make a difference? Or the amount of contact time isn't enough to make a difference? Why are the results the same regardless of sparge water temperature?