I'm afraid I don't know anything about the effects of excess calcium ion. It is important in intracellular signalling and yeasts have a transport mechanism to get it into the cell and I suppose it is possible to overwhelm that system but I would think that there would be some regulatory mechanism involved such that no more than is needed would be taken in. Putting aside absurdities such as concentration sufficient to produce excess osmotic pressure about all I can offer is 'too much of a good thing' and that isn't very helpful I'm sure.

Now what really got me thinking with respect to calcium in brewing was:

Much of any calcium added to the mash will be deposited there or in later stages while its sulphates or chlorides mostly reach the finished product.

Malts are typically 0.13% calcium [Briggs] which means 1.3 grams per kg and if mashed with 2 L of water (easy for the math) and assuming that this leads to 3.2 L beer the available calcium per liter of beer from the barley is 406 mg (20 mEq)/L. Beer contains typically much less than this. From [H,B,S &Y]: 40 - 140 mg (2 - 7 mEq)/L for British beers 3.8 - 102 mg (.194 - 5.1 mEq)/L and 10 - 135 mg (0.5 - 6.75 mEq)/L for 'lagers'. Some lagers are brewed with very soft water and we might assume that the beers with the lowest calcium contents are brewed with the softest water. This makes it appear that, in the limit as water approaches 0 hardness something like 20 mEq of calcium are precipitated from the amount of water equivalent to a liter of finished beer. This, in turn leads to the hypothesis that

at least this much calcium must be precipitated from any beer. Part of the support for this is that 20 mEq of calcium is 10 mmol (576 mg). Malt is typicall 1.25% phosphate [Briggs] so that the equivalent potential concentration in the finished beer is 12500/3.2 = 3906 mg/L. Thus only about 15% of the malt's phosphate is required to precipitate all its calcium and note that calcium precipitates in other ways.

Applying this hypothesis to beer with higher calcium e.g. one at the upper end of the spectrum with 7 mEq/L (beer) concentration we conclude that

at least 7 mEq calcium, referenced to the beer must have been present in the source water. Assuming that the sparge and source water are the same this implies CaSO4 content of 3.5 mmol which is 602 mg/L of the dihydrate. This is about what I gather the more avid fans of Burtonization use so perhaps out hypothesis, while hardly solidly proven, is not so unreasonable and it is clear that calcium added to the brewing liquor or water does make it through to the beer. Of course we don't know whether those surviving ions came from the malt or the addition but it seems to be true that if you add more calcium to the brew pot you'll have more calcium in the beer.

Now lets suppose that we have added 7 mEq/L of calcium all on the hot side and that the only dilutions we do are on the hot side. Kolbach tells us that 2 mEq of hydrogen ions should be produced. As 10 mEq of calcium produce 14 mEq of protons in the phosphate reaction it is apparent that 10/7 = 1.43 are produced by these 7 mEq of calcium and that of the 7 only 1.43 are precipitated with calcium. Further evidence that calcium survives but note again as we have before that there are other ways in which calcium can precipitate.

Thus although it looks to me as if a good part of the calcium added on the hot side is not going to be precipitated there is certainly no argument that any calcium added on the cold side will be.

...

View attachment 563881 meanwhile the phosphates and oxalates deposited can reduce the buffering effect and requirement to acidify the finished product.

This caught my eye because I've seen it before in some of the older literature and it never made much sense to me.

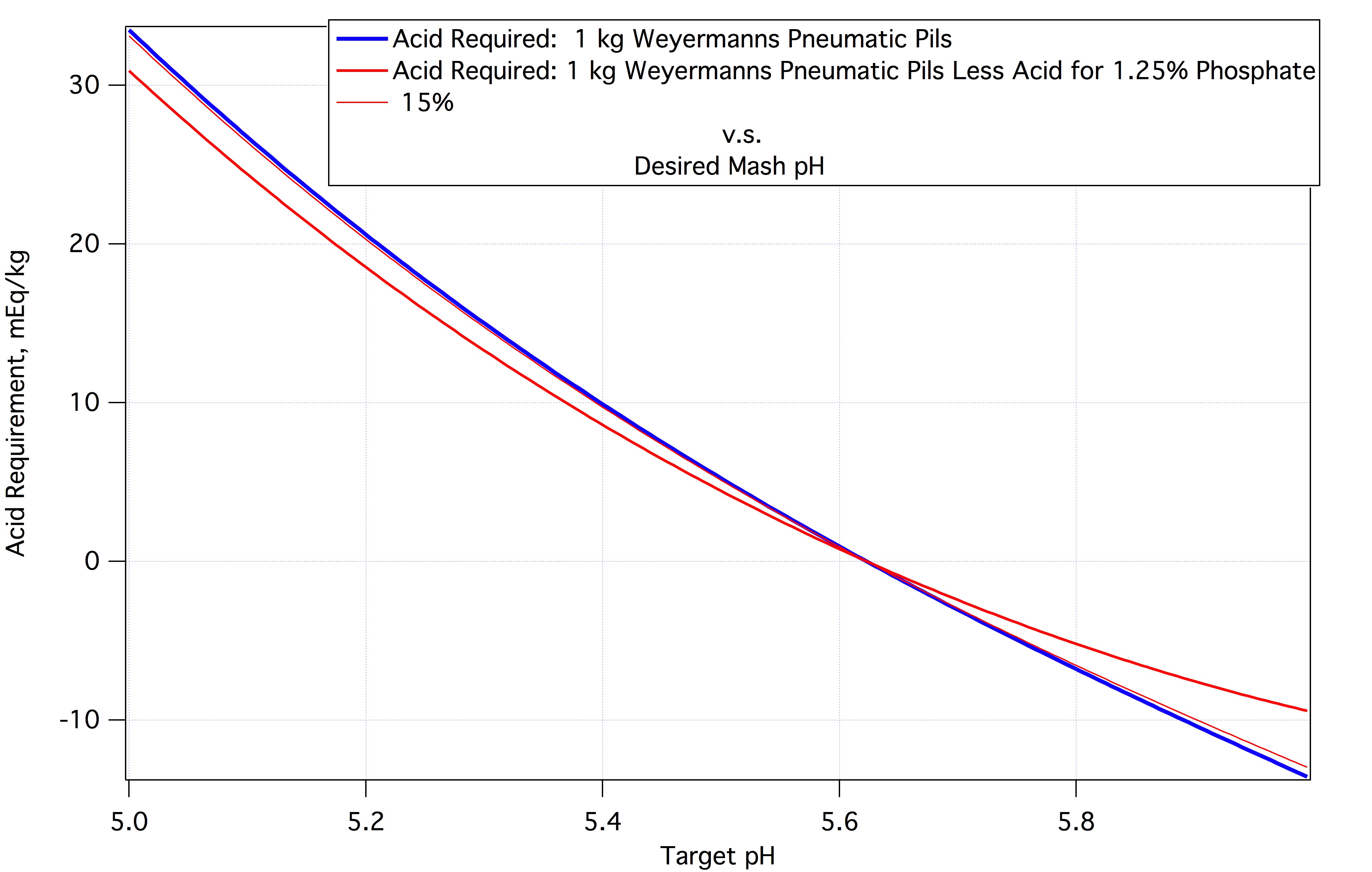

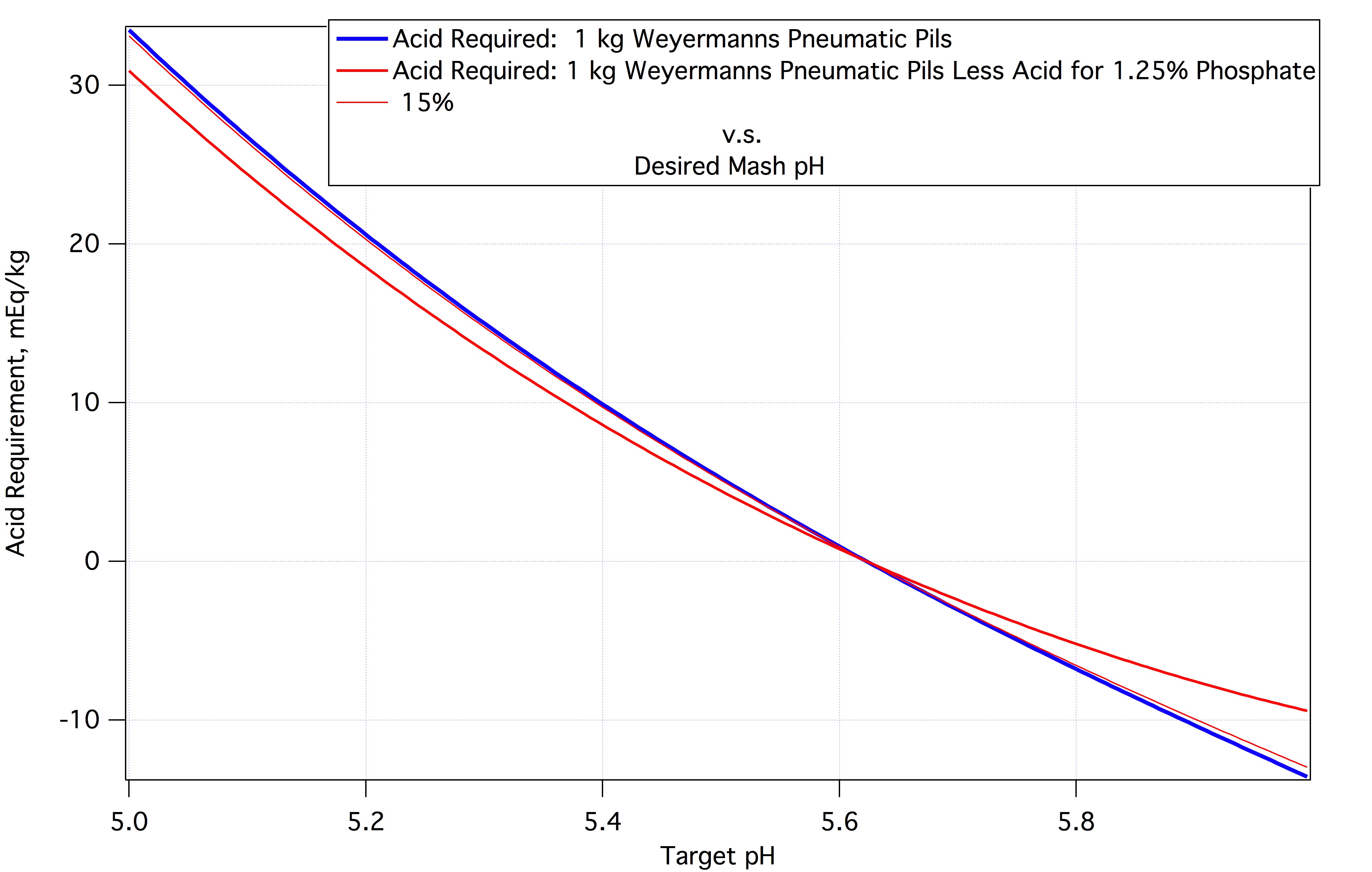

Let's go back to the observation that malt typically contains 1.25% phosphate as H2PO3--. The graph below shows two curves. The blue curve shows (vertical axis) the acid that must be added to 1 kg of Weyermann's regular Pilsner malt to get it to the mash pH's indicated on the horizontal axis. This curve represents real measured data. It crosses the 0 axis at pH 5.62 which is the DI mash pH for this malt. The red curve assumes that this malt contains 1.25% phosphate and that all of it is unbound such that it can react with calcium which it is assumed to do. Without the phosphate less acid is required to lower the pH by a given amount.

But we have observed that not all the phosphate is precipitated by any means. Fifteen percent of it covers all the malt calcium and as some calcium is precipitated with proteins less than 15% of the buffering of the phosphate system should actually be deducted. The thin red line on the chart (labeled 15%) is discernably different from the blue line at the right side of the plot) represents the titration data with 15% of 1.26% deducted.

Now this represents no added calcium. As we know, if we added 7 mEq calcium it should produce 2 mEq protons at knockout. In the mash we might see half that so that the thin curve would come down by 1 mEq at every point. At a nominal mash pH of 4.5 that's 10% of the acid requirement which is enough that it should be taken into account bu those doing heavy Burtonization.

Note that the slope of the blue curve -1 mEq is the same as the slope of the blue curve so that the buffering is actually not changed at all. That's in part why this caught my eye. It's much simpler to say that each mEq of added calcium produces 1/3.5 mEq acid than it is to try to explain it in terms of the phosphate buffering system