I now have 4 corny kegs which I use only for bitters, I do exactly what DD says above. All my other beers including British Pales, IPA’s, Stouts and Brown Ales are bottled.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

My Quest for Real Ale

- Thread starter kirkpierce

- Start date

-

- Tags

- beer engine real ale

Help Support Homebrew Talk:

This site may earn a commission from merchant affiliate

links, including eBay, Amazon, and others.

85-90% base? What's the rest then? I'd say, go for 94 % -100 % base malt. That is more realistic. I don't know about many Britsh beers that have much more than 5% crystal for example. Actually, now that I am thinking about it, I do not know any.If you’re an AHA member I gave a seminar on brewing English ales at Homebrew Con 2022 in Pittsburgh. https://www.homebrewersassociation.org/seminar/english-ales-from-classics-to-class/

Key takeaways:

1) Pick a base malt you like and let it shine. Most of my recipes are 85-90% base malt.

2) The balance should be crisp, not heavy or malty.

I don’t touch on packaging in the talk. If you’re going for real ale/cask ale, the easiest way is to bottle condition with low carbonation. If kegging, you’ll want a separate cool box/keezer at cellar temperature, and jury rig your keg to gravity dispense if you don’t have a beer engine. A friend wrote a detailed post on this, but I think it’s been taken down.

Never go below 90% Pale Malt, make the rest up as you please.

Pennine

Well Known Fool

- Joined

- Sep 10, 2019

- Messages

- 527

- Reaction score

- 2,516

I have had good luck serving in a corny and adding CO2 in doses rather than constant pressure. Usually I can get it to the right level of initial carbonation and then add in low levels when there isn't enough pressure to serve within the keg.English ales aren't uniformly crisp, not on England anyway. But maybe there's a tendency on your side of the pond to go too heavy on the malt, I see malt heavy recipes quite often. Loads of crystal malt for example. So yes, 85-90% base is good for a lot of English ales, I think.

Yeast is important too. It's a struggle with dried yeast, at this point in time. Maybe we will get a better dried English yeast at some point.

I have friends here who serve English ale from cornies. And do a good job of it. If the beer is unpasteurised and unfiltered, and primed in the keg, and there's just enough gas applied to push the beer out of the keg, you can get a good result with English ales, very similar to cask, and I should do it myself. The only tangible difference with cask (off the top of my head) is that CO2 replaces the beer as it is drawn, instead of air. Which is a positive in my eyes.

My Porter recipe85-90% base? What's the rest then? I'd say, go for 94 % -100 % base malt. That is more realistic. I don't know about many Britsh beers that have much more than 5% crystal for example. Actually, now that I am thinking about it, I do not know any.

87.3% Spring Pale Malt

5.5% Chocolate

4.9% Wheat

2.5% Crystal 150L

duncan_disorderly

Well-Known Member

Are you in the Pennines? I'm on the edge.I have had good luck serving in a corny and adding CO2 in doses rather than constant pressure. Usually I can get it to the right level of initial carbonation and then add in low levels when there isn't enough pressure to serve within the keg.

$479.00

$559.00

EdgeStar KC1000SS Craft Brew Kegerator for 1/6 Barrel and Cornelius Kegs

Amazon.com

$44.99

$49.95

Craft A Brew - Mead Making Kit – Reusable Make Your Own Mead Kit – Yields 1 Gallon of Mead

Craft a Brew

$33.99 ($17.00 / Count)

$41.99 ($21.00 / Count)

2 Pack 1 Gallon Large Fermentation Jars with 3 Airlocks and 2 SCREW Lids(100% Airtight Heavy Duty Lid w Silicone) - Wide Mouth Glass Jars w Scale Mark - Pickle Jars for Sauerkraut, Sourdough Starter

Qianfenie Direct

$76.92 ($2,179.04 / Ounce)

Brewing accessories 1.5" Tri Clamp to Ball Lock Post Liquid Gas Homebrew Kegging Fermentation Parts Brewer Hardware SUS304 Brewing accessories(Gas Hose Barb)

chuhanhandianzishangwu

$7.79 ($7.79 / Count)

Craft A Brew - LalBrew Voss™ - Kveik Ale Yeast - For Craft Lagers - Ingredients for Home Brewing - Beer Making Supplies - (1 Pack)

Craft a Brew

$22.00 ($623.23 / Ounce)

AMZLMPKNTW Ball Lock Sample Faucet 30cm Reinforced Silicone Hose Secondary Fermentation Homebrew Kegging joyful

无为中南商贸有限公司

![Craft A Brew - Safale S-04 Dry Yeast - Fermentis - English Ale Dry Yeast - For English and American Ales and Hard Apple Ciders - Ingredients for Home Brewing - Beer Making Supplies - [1 Pack]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/41fVGNh6JfL._SL500_.jpg)

$6.95 ($17.38 / Ounce)

$7.47 ($18.68 / Ounce)

Craft A Brew - Safale S-04 Dry Yeast - Fermentis - English Ale Dry Yeast - For English and American Ales and Hard Apple Ciders - Ingredients for Home Brewing - Beer Making Supplies - [1 Pack]

Hobby Homebrew

$49.95 ($0.08 / Fl Oz)

$52.99 ($0.08 / Fl Oz)

Brewer's Best - 1073 - Home Brew Beer Ingredient Kit (5 gallon), (Blueberry Honey Ale) Golden

Amazon.com

$20.94

$29.99

The Brew Your Own Big Book of Clone Recipes: Featuring 300 Homebrew Recipes from Your Favorite Breweries

Amazon.com

$53.24

1pc Hose Barb/MFL 1.5" Tri Clamp to Ball Lock Post Liquid Gas Homebrew Kegging Fermentation Parts Brewer Hardware SUS304(Gas MFL)

Guangshui Weilu You Trading Co., Ltd

$719.00

$799.00

EdgeStar KC2000TWIN Full Size Dual Tap Kegerator & Draft Beer Dispenser - Black

Amazon.com

$58.16

HUIZHUGS Brewing Equipment Keg Ball Lock Faucet 30cm Reinforced Silicone Hose Secondary Fermentation Homebrew Kegging Brewing Equipment

xiangshuizhenzhanglingfengshop

$53.24

1pc Hose Barb/MFL 1.5" Tri Clamp to Ball Lock Post Liquid Gas Homebrew Kegging Fermentation Parts Brewer Hardware SUS304(Liquid Hose Barb)

yunchengshiyanhuqucuichendianzishangwuyouxiangongsi

$176.97

1pc Commercial Keg Manifold 2" Tri Clamp,Ball Lock Tapping Head,Pressure Gauge/Adjustable PRV for Kegging,Fermentation Control

hanhanbaihuoxiaoshoudian

Pennine

Well Known Fool

- Joined

- Sep 10, 2019

- Messages

- 527

- Reaction score

- 2,516

No unfortunately not, I used to spend a lot of time in the area running and biking. I'm on the edge of the front range nowAre you in the Pennines? I'm on the edge.

duncan_disorderly

Well-Known Member

No unfortunately not, I used to spend a lot of time in the area running and biking. I'm on the edge of the front range now

OK, let's cut out dark beers and pretend that wheat and barley are just base malts, because this is what they actually deliver flavour wise.My Porter recipe

87.3% Spring Pale Malt

5.5% Chocolate

4.9% Wheat

2.5% Crystal 150L

Northern_Brewer

British - apparently some US company stole my name

Well the Fulller's partigyle is an obvious one, at ~7.2% light crystal, but that's certainly up at the higher end. I suspect Hobgoblin may be even higher but then that's the Thames Valley for you, at one extreme. OTOH, it's just as normal for British bitter to have no crystal at all. So yeah, US brewers tend to put way too much crystal and would be much better heading for an average of say 3%, or balancing out a bit more with invert, but it's not the only thing that goes wrong with US bitter.85-90% base? What's the rest then? I'd say, go for 94 % -100 % base malt. That is more realistic. I don't know about many Britsh beers that have much more than 5% crystal for example. Actually, now that I am thinking about it, I do not know any.

Anyway, I talked a bit about yeast for bitter over on THBF, and it's worth repeating here the quotes from the two co-founders of Cloudwater. For those that don't know Cloudwater is arguably the leading modern brewery in the UK, at one point Ratebeer put them #2 in the world behind Hill Farmstead, so ahead of Trillium, Treehouse, Other Half etc. So Cloudwater know their stuff. They do not use S-04 and Notty for their bitters...

Paul Jones is quoted in a great new article from Jeff Alworth on modern bitter, and an accompanying blog :

https://beerandbrewing.com/style-school-cask-bitter/

https://www.beervanablog.com/beervana/2025/4/7/the-evolution-of-cask-bitter

“Yeast is by far the most important ingredient in bitter,” says Paul Jones, cofounder of the Manchester-based brewery Cloudwater. After all, house yeasts are what made those legacy bitters distinctive. “It’s what makes someone a fan of J.W. Lees, but not so much of Holt’s, or a fan of Holt’s but not so much Harvey’s.

James Kemp used to blog at Port 66 :

https://web.archive.org/web/2018041...co.uk/yeast-brewing-myths-ideal-house-strain/

what is it about [trad bitter] that makes them so interesting and amazing? I’d thought for a while that it was malt character and quality and especially malt complexity that help create such an interesting beer at a modest abv. This was certainly a tack I tried to take when I was brewing commercially but when you look at these beers and their recipes you’ll find them to be simple and very much the same....This really doesn’t leave much else apart from yeast and that in fact I think is the key, traditional British beers, even though they are fairly ubiquitous are exceptional because the main character building ingredient is the yeast....

when I started at Thornbridge we used a yeast strain that came from Holt’s brewery in Manchester, not the sexiest brewery in the UK and certainly not a hop forward US style brewery but the yeast is fantastic and Thornbridge took the UK beer industry by storm with a range of expressive US style hop driven beers. I left Thornbridge and became the Head Brewer at Buxton, I quickly ditched the yeast Buxton were using and put in place the same strain brewing some excellent beers. This strain

yeast isn’t just there to do a job it’s a crucial part of flavour and aroma complexity, a lot of my experimental brewing involves split batch fermented beer to compare and contrast the impact that a yeast strain has on the finished beer and the results are astonishing.

As a dumb Yank that focuses on small UK ales, I've learned that's the best method. It has served me well for decades at this point. As much as I'd like to run a cask program, there's no getting around that fact that I can't properly dispense and drink 5-6gals of bitter in a timely enough fashion to warrant trying to approximate a cask system. Bursting gas in for serving, then bleeding it off at the end of a session is a workable compromise. CAMRA will look down their noses at me, but they don't drink my beers, so they can piss off.I have had good luck serving in a corny and adding CO2 in doses rather than constant pressure. Usually I can get it to the right level of initial carbonation and then add in low levels when there isn't enough pressure to serve within the keg.

Pennine

Well Known Fool

- Joined

- Sep 10, 2019

- Messages

- 527

- Reaction score

- 2,516

Yeah I have been tempted to rig up a beer engine to the corny. I might pick a reasonably priced one up on a trip later this year.As a dumb Yank that focuses on small UK ales, I've learned that's the best method. It has served me well for decades at this point. As much as I'd like to run a cask program, there's no getting around that fact that I can't properly dispense and drink 5-6gals of bitter in a timely enough fashion to warrant trying to approximate a cask system. Bursting gas in for serving, then bleeding it off at the end of a session is a workable compromise. CAMRA will look down their noses at me, but they don't drink my beers, so they can piss off.

On another note I think if we just naturally carb the keg we would be CAMRA compliant. Someone smarter than me will chime in if that's true or not.

duncan_disorderly

Well-Known Member

When I chatted to Joe Ince the person I was with asked him why he doesn't use English hops he said "because they are terrible." I said that's a matter of opinion, because my preference is for English hops in cask ales, and things got tense!Well the Fulller's partigyle is an obvious one, at ~7.2% light crystal, but that's certainly up at the higher end. I suspect Hobgoblin may be even higher but then that's the Thames Valley for you, at one extreme. OTOH, it's just as normal for British bitter to have no crystal at all. So yeah, US brewers tend to put way too much crystal and would be much better heading for an average of say 3%, or balancing out a bit more with invert, but it's not the only thing that goes wrong with US bitter.

Anyway, I talked a bit about yeast for bitter over on THBF, and it's worth repeating here the quotes from the two co-founders of Cloudwater. For those that don't know Cloudwater is arguably the leading modern brewery in the UK, at one point Ratebeer put them #2 in the world behind Hill Farmstead, so ahead of Trillium, Treehouse, Other Half etc. So Cloudwater know their stuff. They do not use S-04 and Notty for their bitters...

Paul Jones is quoted in a great new article from Jeff Alworth on modern bitter, and an accompanying blog :

https://beerandbrewing.com/style-school-cask-bitter/

https://www.beervanablog.com/beervana/2025/4/7/the-evolution-of-cask-bitter

“Yeast is by far the most important ingredient in bitter,” says Paul Jones, cofounder of the Manchester-based brewery Cloudwater. After all, house yeasts are what made those legacy bitters distinctive. “It’s what makes someone a fan of J.W. Lees, but not so much of Holt’s, or a fan of Holt’s but not so much Harvey’s.

James Kemp used to blog at Port 66 :

https://web.archive.org/web/2018041...co.uk/yeast-brewing-myths-ideal-house-strain/

what is it about [trad bitter] that makes them so interesting and amazing? I’d thought for a while that it was malt character and quality and especially malt complexity that help create such an interesting beer at a modest abv. This was certainly a tack I tried to take when I was brewing commercially but when you look at these beers and their recipes you’ll find them to be simple and very much the same....This really doesn’t leave much else apart from yeast and that in fact I think is the key, traditional British beers, even though they are fairly ubiquitous are exceptional because the main character building ingredient is the yeast....

when I started at Thornbridge we used a yeast strain that came from Holt’s brewery in Manchester, not the sexiest brewery in the UK and certainly not a hop forward US style brewery but the yeast is fantastic and Thornbridge took the UK beer industry by storm with a range of expressive US style hop driven beers. I left Thornbridge and became the Head Brewer at Buxton, I quickly ditched the yeast Buxton were using and put in place the same strain brewing some excellent beers. This strainis[was but no more??] also used by Brewdog for Punk IPA and Jackhammer and adds to the character in amazing ways...

yeast isn’t just there to do a job it’s a crucial part of flavour and aroma complexity, a lot of my experimental brewing involves split batch fermented beer to compare and contrast the impact that a yeast strain has on the finished beer and the results are astonishing.

We all want cask to survive and thrive, but some of us are also very keen for English hops to survive and thrive too. It's getting harder to find cask ales that are import free. A lot harder. At one point around ten years ago it seemed as if exports to the US might keep English hops growers in business, but that avenue seems to have narrowed a fair bit?

Interesting, thanks.Well the Fulller's partigyle is an obvious one, at ~7.2% light crystal, but that's certainly up at the higher end. I suspect Hobgoblin may be even higher but then that's the Thames Valley for you, at one extreme. OTOH, it's just as normal for British bitter to have no crystal at all. So yeah, US brewers tend to put way too much crystal and would be much better heading for an average of say 3%, or balancing out a bit more with invert, but it's not the only thing that goes wrong with US bitter.

Anyway, I talked a bit about yeast for bitter over on THBF, and it's worth repeating here the quotes from the two co-founders of Cloudwater. For those that don't know Cloudwater is arguably the leading modern brewery in the UK, at one point Ratebeer put them #2 in the world behind Hill Farmstead, so ahead of Trillium, Treehouse, Other Half etc. So Cloudwater know their stuff. They do not use S-04 and Notty for their bitters...

Paul Jones is quoted in a great new article from Jeff Alworth on modern bitter, and an accompanying blog :

https://beerandbrewing.com/style-school-cask-bitter/

https://www.beervanablog.com/beervana/2025/4/7/the-evolution-of-cask-bitter

“Yeast is by far the most important ingredient in bitter,” says Paul Jones, cofounder of the Manchester-based brewery Cloudwater. After all, house yeasts are what made those legacy bitters distinctive. “It’s what makes someone a fan of J.W. Lees, but not so much of Holt’s, or a fan of Holt’s but not so much Harvey’s.

James Kemp used to blog at Port 66 :

https://web.archive.org/web/2018041...co.uk/yeast-brewing-myths-ideal-house-strain/

what is it about [trad bitter] that makes them so interesting and amazing? I’d thought for a while that it was malt character and quality and especially malt complexity that help create such an interesting beer at a modest abv. This was certainly a tack I tried to take when I was brewing commercially but when you look at these beers and their recipes you’ll find them to be simple and very much the same....This really doesn’t leave much else apart from yeast and that in fact I think is the key, traditional British beers, even though they are fairly ubiquitous are exceptional because the main character building ingredient is the yeast....

when I started at Thornbridge we used a yeast strain that came from Holt’s brewery in Manchester, not the sexiest brewery in the UK and certainly not a hop forward US style brewery but the yeast is fantastic and Thornbridge took the UK beer industry by storm with a range of expressive US style hop driven beers. I left Thornbridge and became the Head Brewer at Buxton, I quickly ditched the yeast Buxton were using and put in place the same strain brewing some excellent beers. This strainis[was but no more??] also used by Brewdog for Punk IPA and Jackhammer and adds to the character in amazing ways...

yeast isn’t just there to do a job it’s a crucial part of flavour and aroma complexity, a lot of my experimental brewing involves split batch fermented beer to compare and contrast the impact that a yeast strain has on the finished beer and the results are astonishing.

Funny side fact: Cloudwater happens to be the only brewery that managed to show me diacetyl in one of their beers. A lager that tasted like liquid butter.

All their other beers were fine tbh. But that one forever made them the "pop corn brewery" in my mind.

By any chance, do you know which yeast he is referring to? Or to rephrase it more appropriately, do you know which yeast one could buy to get close to the one he is using?

duncan_disorderly

Well-Known Member

Cloudwater became big news very quickly with James Campbell as head brewer, he only stayed a couple of years and their profile has dropped somewhat since. It is primarily an American style craft brewer, of course.Interesting, thanks.

Funny side fact: Cloudwater happens to be the only brewery that managed to show me diacetyl in one of their beers. A lager that tasted like liquid butter.

All their other beers were fine tbh. But that one forever made them the "pop corn brewery" in my mind.

By any chance, do you know which yeast he is referring to? Or to rephrase it more appropriately, do you know which yeast one could buy to get close to the one he is using?

Marble is much more cask focussed. I am much more a Marble drinker. James Kemp had a good spell at Marble himself. He got the Holt's yeast from Holt's brewery, iirc, very close to Marble at the time. I've considered asking a Holt's pub for some cask dregs but never got rounmd to it, yet.

An Ankoù

Well-Known Member

I agree with that sentiment entirely. Bunch of elfin bankers!CAMRA will look down their noses at me, but they don't drink my beers, so they can piss off.

Cask beer will be fairly carbonated when the cask is newly broached, and that will vent through the porous peg until an equilibrium is reached. I find that real ale put in 10 litre kegs with a of bit priming sugar dispenses nicely for a couple of pints and, depending on the beer, can be more like cream flow. Then, as the gas comes out of solution and into the newly-created headspace, the beer settles down to a lower level of carbonation and the liberated gas is sufficient to dispense up to half the beer. After that, top pressure is applied to dispense the rest of the beer, not to carbonate it. I see little point in venting the keg after service as it should only be at about 5 to 10 psi, if that.

I don't know if you get party kegs in the US, but they show the same principle. If you avoid venting until the beer flow becomes a trickle then it's the same as what I described above, except that at some stage you have to open the vent to allow air in.

At what point is it "real ale"? Is it only when the air is allowed to fill the ullage? Even though the first few pints are still saturated with CO2?

Cask dispense is important, indeed critical, but it's not the whole story.

As for CAMRA's notion of "real ale in a bottle", we'll that's another story.

An Ankoù

Well-Known Member

That's interesting. Why does this Ince guy think English hops are terrible? They're amazing. I've stopped ordering US and Pacific hops to give a bit of time to English and French hops. Harlequin is a splendid hop that can easily knock the socks off anything coming over the oceans. Phoenix is unique. Challenge, Bramling X, and WGV even can be an eye opener in the right beer.When I chatted to Joe Ince the person I was with asked him why he doesn't use English hops he said "because they are terrible." I said that's a matter of opinion, because my preference is for English hops in cask ales, and things got tense!

We all want cask to survive and thrive, but some of us are also very keen for English hops to survive and thrive too. It's getting harder to find cask ales that are import free. A lot harder. At one point around ten years ago it seemed as if exports to the US might keep English hops growers in business, but that avenue seems to have narrowed a fair bit?

Perhaps this Ince fellow just can't brew with them.

Edit

Just googled and found Marble Beers. Manchester.

Will investigate later.

The range doesn't look very trad to me though.

duncan_disorderly

Well-Known Member

He just hates them. I just pointed out a lot of people like them. He is an excellent brewer though, I drink a lot of his stuff!That's interesting. Why does this Ince guy think English hops are terrible? They're amazing. I've stopped ordering US and Pacific hops to give a bit of time to English and French hops. Harlequin is a splendid hop that can easily knock the socks off anything coming over the oceans. Phoenix is unique. Challenge, Bramling X, and WGV even can be an eye opener in the right beer.

Perhaps this Ince fellow just can't be with them.

An Ankoù

Well-Known Member

Fair 'nuff.He just hates them. I just pointed out a lot of people like them. He is an excellent brewer though, I drink a lot of his stuff!

duncan_disorderly

Well-Known Member

If bottle conditioned beer classes as real ale due to its natural carbonation, then naturally conditioned keg beer should also qualify as real ale, surely?As for CAMRA's notion of "real ale in a bottle", we'll that's another story.

I just think the word 'keg' had satanic overtones for Camra, for a very long time, and possibly still has for some of them.

An Ankoù

Well-Known Member

I'd go along with that except that I wonder about their reluctance to approve using cask breathers. It makes me think that the process of oxidation through aeration should have already started. A bit like letting a wine "breathe". But that would start in the glass anyway.If bottle conditioned beer classes as real ale due to its natural carbonation, then naturally conditioned keg beer should also qualify as real ale, surely?

I just think the word 'keg' had satanic overtones for Camra, for a very long time, and possibly still has for some of them.

Yes. I've now convinced myself that I'm over thinking this and they probably had a holy horror of CO2 bottles. A bit of a contradiction for a pressure group.

I'll stick with the Beer From The Wood lot, even if the only two pints I ever had from the wood were pretty poor.

Last edited:

duncan_disorderly

Well-Known Member

Although they have approved cask breathers obviously.I'd go along with that except that I wonder about their reluctance to approve using cask breathers. It makes me think that the process of oxidation through aeration should have already started. A bit like letting a wine "breathe". But that would start in the glass anyway.

Yes. I've now convinced myself that I'm over thinking this and they probably had a holy horror of CO2 bottles. A bit of a contradicting for a pressure group.

I'll stick with the Beer From The Wood lot, even if the only two pints I ever had from the wood were pretty poor.

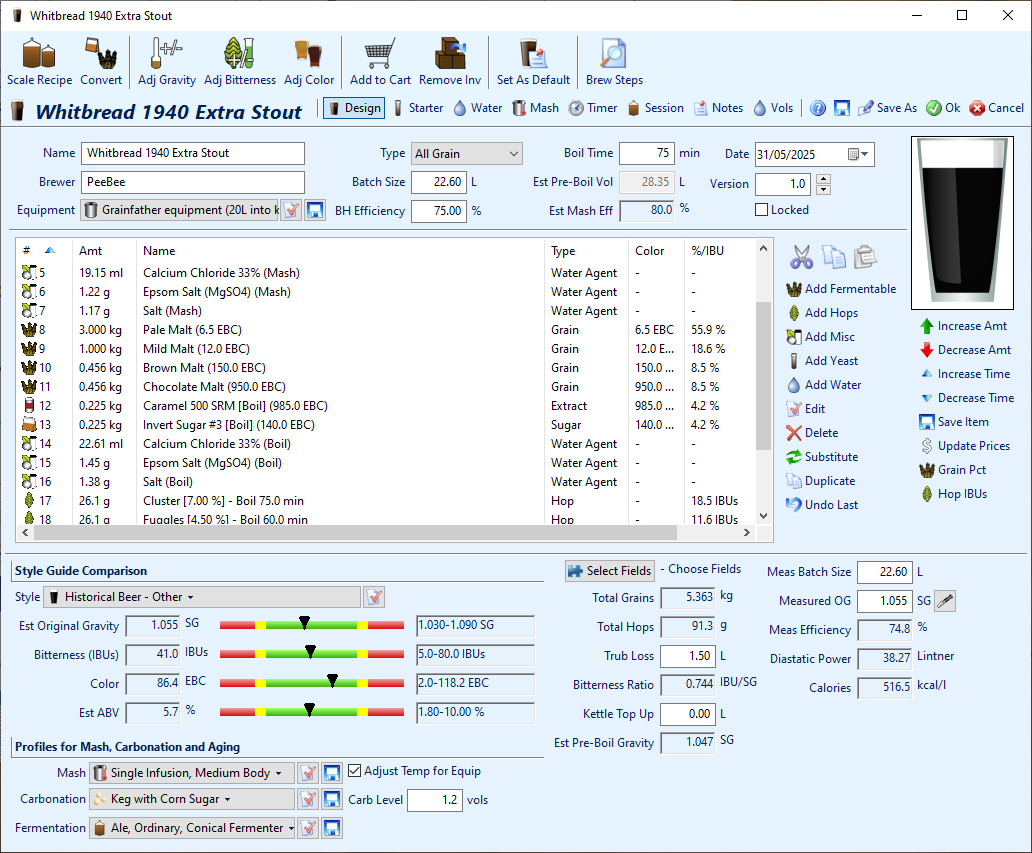

Cor, I missed that. A very risky statement! My next brew, still in planning ...Never go below 90% Pale Malt, make the rest up as you please.

55.9%+ 18.6% = 74.5%. Okay, a historic recipe (wartime) dragged out by Ron Pattinson (his "Stout!" book), but Sam Smith (for one) still churn out an English Stout.

American hops too! Well, it was the thing back then. I'm looking forward to trying the Caramel I've sourced (E150A, not that E150C muck, very important for these recipes).

[EDIT: Hang-on ... this section is "New Member Introductions". Err ... Hi @kirkpierce. Erm ... Welcome to the forum!

I think we'd better release @kirkpierce into the wild now? The conversation is digging a bit deep for this section? Another humongous "English Ales - What's your favorite recipe?" thread opening in this section is going to annoy someone? Perhaps this conversation should move there?]

Last edited:

Similar threads

- Replies

- 60

- Views

- 3K

- Replies

- 8

- Views

- 902

- Replies

- 8

- Views

- 490