navethechimp

Member

Hey guys,

Question

I'm struggling to find reliable resources to understand what gets my beers from their post-boil pH to their final pH in the glass. Anyone have their own evidence or links to some publications? I have been googling and searching the forums for some literature or good resources on this topic. Mash pH is a widely studied and documented topic, so no troubles there.

My Anecdotal Experiences

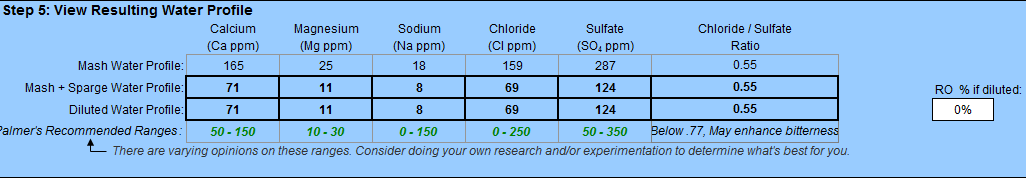

My final beer pH is consistently higher than commercial examples of the same style. I generally brew low to mid strength pale beers, both lagers and ales. My pH meter usually reads 4.5 to 4.7 pH on my finished product, with no obvious flavor defects. My water profiles are very soft, fully built up from bottled distilled--little to no hardness and with 50-150 ppm of the aesthetic ions, depending on the style. My mash pH is usually 5.3-5.4 and I get fine conversion. I don't add salts to my sparge water, but I do acidify it to make sure I hit my target boil pH. Commercial examples of the same styles generally range between 4.2 to 4.5 pH on the same meter, including everything from a world class IPA to a pale ale or a Weihenstephaner pils to a Modelo Especial. What is driving me crazy is that I can add phosphoric acid to my finished beer to get it to a similar level in a side-by-side tasting with a commercial equivalent, and the increased brightness improves the flavor of the beer--usually getting it as good or better than the commercial one I am comparing it to. Why do I have to add acid post fermentation to take it from good to great, rather than letting yeast and other upstream processes take care of it?

Possible Factors

FWIW, this is the most valuable thread I have been able to find, but it's mostly a reference, not really helping me understand why:

https://www.homebrewtalk.com/showthread.php?t=469197

Thanks guys!

Question

I'm struggling to find reliable resources to understand what gets my beers from their post-boil pH to their final pH in the glass. Anyone have their own evidence or links to some publications? I have been googling and searching the forums for some literature or good resources on this topic. Mash pH is a widely studied and documented topic, so no troubles there.

My Anecdotal Experiences

My final beer pH is consistently higher than commercial examples of the same style. I generally brew low to mid strength pale beers, both lagers and ales. My pH meter usually reads 4.5 to 4.7 pH on my finished product, with no obvious flavor defects. My water profiles are very soft, fully built up from bottled distilled--little to no hardness and with 50-150 ppm of the aesthetic ions, depending on the style. My mash pH is usually 5.3-5.4 and I get fine conversion. I don't add salts to my sparge water, but I do acidify it to make sure I hit my target boil pH. Commercial examples of the same styles generally range between 4.2 to 4.5 pH on the same meter, including everything from a world class IPA to a pale ale or a Weihenstephaner pils to a Modelo Especial. What is driving me crazy is that I can add phosphoric acid to my finished beer to get it to a similar level in a side-by-side tasting with a commercial equivalent, and the increased brightness improves the flavor of the beer--usually getting it as good or better than the commercial one I am comparing it to. Why do I have to add acid post fermentation to take it from good to great, rather than letting yeast and other upstream processes take care of it?

Possible Factors

- Increased mash, pre-boil, and/or post-boil pH (i.e. pale grain bill, less negatively charged ions from salts) -> final pH higher

- Increased amino acids (from a weak hot break) that buffer around 4.9 pH -> final pH higher

- Increased oxygenation -> final pH ?

- Yeast or bacteria strain -> effect on pH varies by strain

- Increased pitch rate -> final pH ?

- Increased fermentation temperature -> final pH ?

- Longer contact with yeast, leading to autolysis -> final pH higher

- Increased dry hop levels -> final pH higher

- Increased carbonation (and thus carbonic acid) -> final pH ?

- Increased hardness acting as a buffer for the rest of these factors -> final pH higher

FWIW, this is the most valuable thread I have been able to find, but it's mostly a reference, not really helping me understand why:

https://www.homebrewtalk.com/showthread.php?t=469197

Thanks guys!