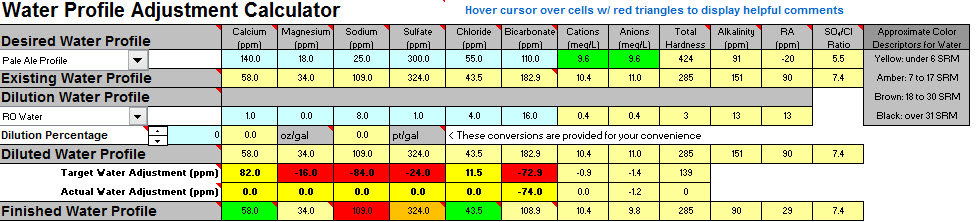

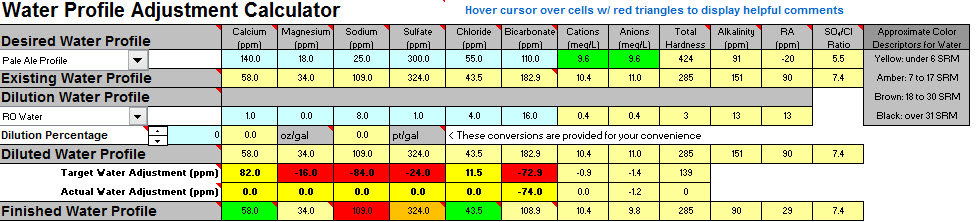

So I decided to look at my water profile using Bru'n Water to see if I should be adjusting anything.

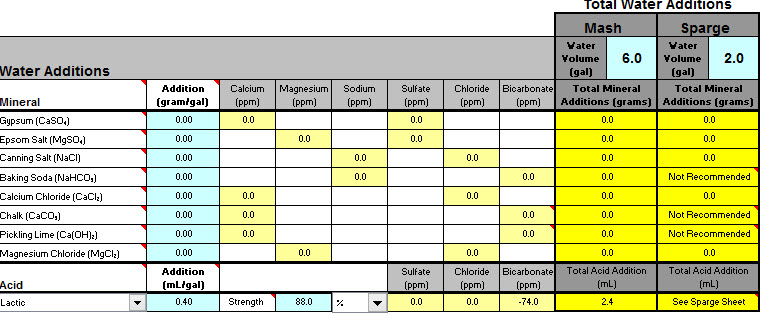

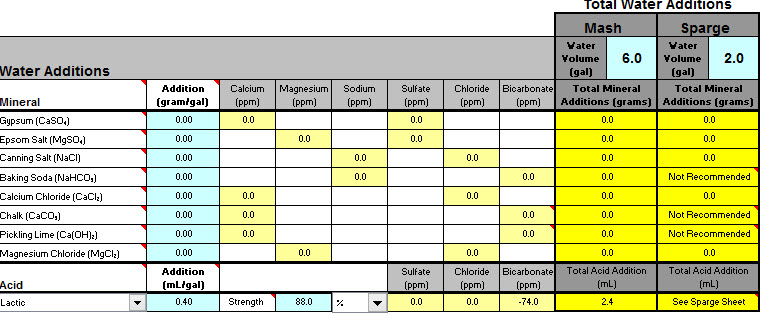

I plan on brewing the Bells 2 Hearted Clone Recipe from this site. After working my way through the sheets it looks like my water (without dilution) will be acceptable for brewing using the pale ale profile other then both the mash and sparge needing additions of lactic acid to bring the ph into range.

My sodium content does appear to be outside of the range (but below the max 150ppm) which looks like it can be corrected with a small dilution of water if required. Hoping to avoid this unless being much lower will make an important difference

I was hoping someone could take a look and tell me if I'm missing something or if I should be making any other adjustments.

Thanks in advance

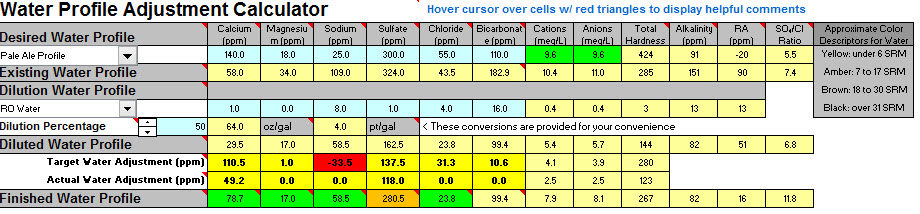

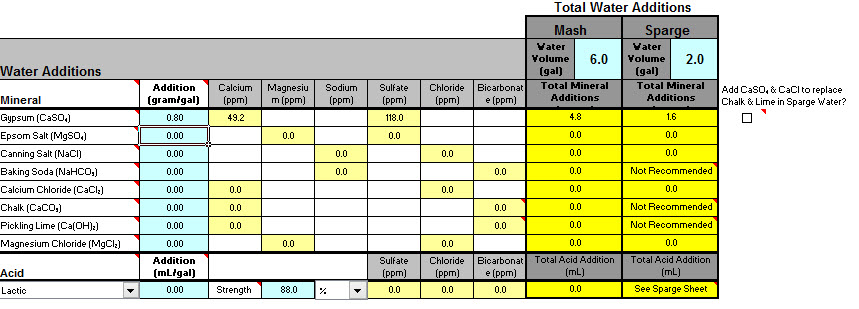

I plan on brewing the Bells 2 Hearted Clone Recipe from this site. After working my way through the sheets it looks like my water (without dilution) will be acceptable for brewing using the pale ale profile other then both the mash and sparge needing additions of lactic acid to bring the ph into range.

My sodium content does appear to be outside of the range (but below the max 150ppm) which looks like it can be corrected with a small dilution of water if required. Hoping to avoid this unless being much lower will make an important difference

I was hoping someone could take a look and tell me if I'm missing something or if I should be making any other adjustments.

Thanks in advance