SmokinBarleyPops

Member

My kolsch is nearing the end of its diacetyl rest and i am wondering if should transfer to a secondary before sending to it lagering temp.

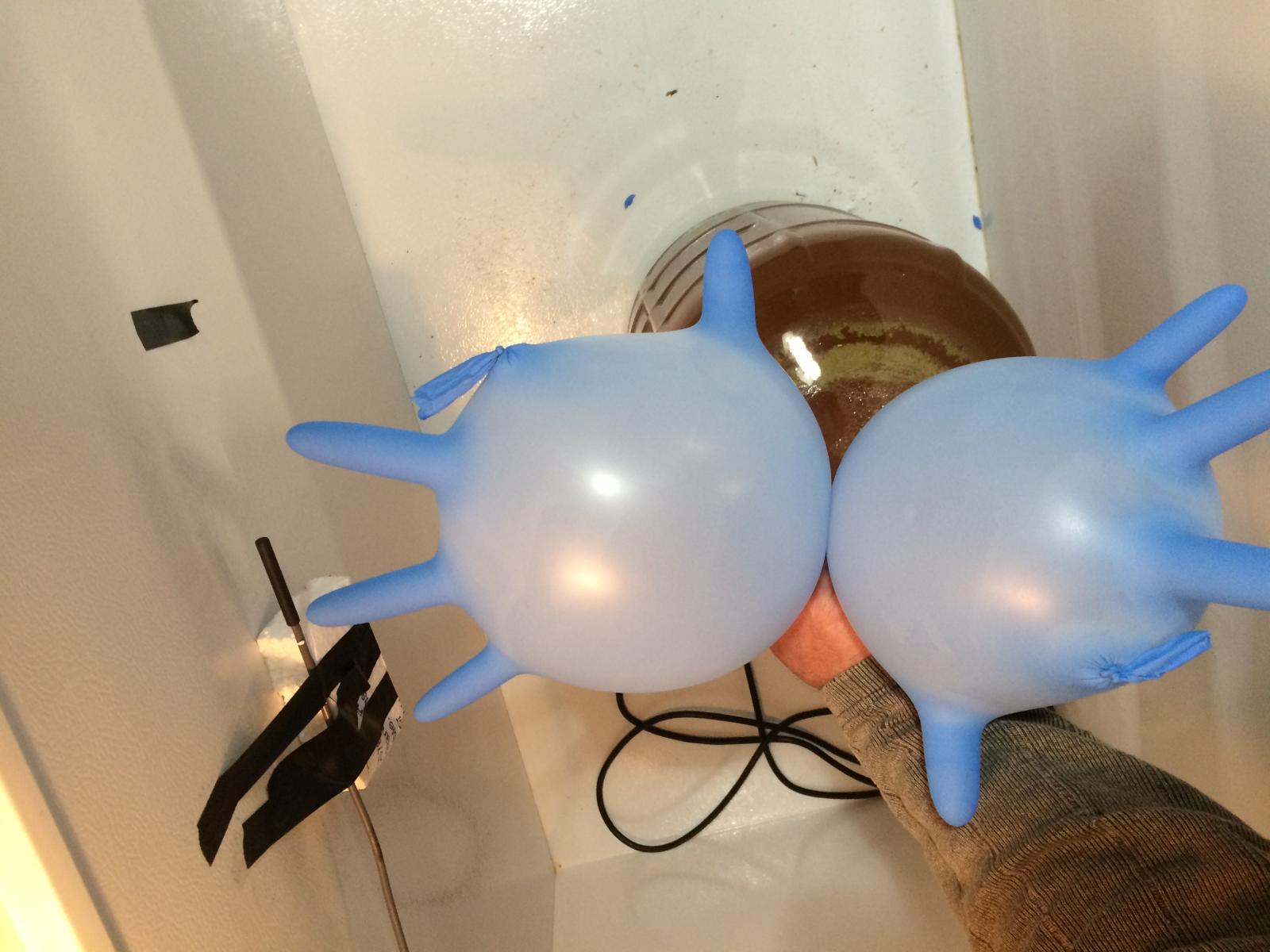

I am attaching a pic of my carboy currently. It appears there is a large amount of krausen and yeast stuck to the top and neck.

What would you do. Ferment is complete fg of about 1.009. Plan on lowering the temp from 68 to 40 degrees over 4 days, then 2 weeks a 40.View attachment 1422917176627.jpg

Also am I ok to keep it set up as a blowoff to prevent suck back while cooling, or should I just put on some sanitized foil?

I am attaching a pic of my carboy currently. It appears there is a large amount of krausen and yeast stuck to the top and neck.

What would you do. Ferment is complete fg of about 1.009. Plan on lowering the temp from 68 to 40 degrees over 4 days, then 2 weeks a 40.View attachment 1422917176627.jpg

Also am I ok to keep it set up as a blowoff to prevent suck back while cooling, or should I just put on some sanitized foil?

![Craft A Brew - Safale S-04 Dry Yeast - Fermentis - English Ale Dry Yeast - For English and American Ales and Hard Apple Ciders - Ingredients for Home Brewing - Beer Making Supplies - [1 Pack]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/41fVGNh6JfL._SL500_.jpg)