Hi guys,

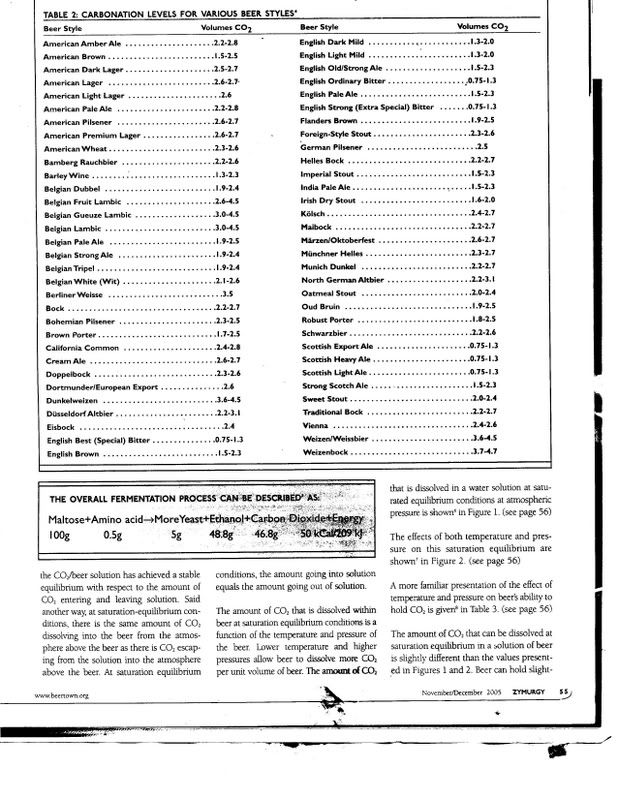

I have been trying to research information regarding how much priming sugar to use for bottle conditioning at different stages of final gravity. What I mean is that if you have a beer with a final gravity of 1.012 vs. another with a final gravity of 1.005, what amount of priming sugar is optimum for each to attain a consistent volume of Co2 in the bottle.

I guess the easy answer is to bottle from a keg with beer already carbonated. That may be true for some styles but when you are talking about Strong Belgians and Bavarian Wizen biers, the sediment from the bottle conditioning is key to some of their flavors.

I have read and used the standard 2/3, 3/4 cup cane sugar in 3 cups of water, boiled then chilled and added to the racked beer before bottling. However, it has been my experience that depending on how much residual fermentable sugar remains in the beer sometimes causes bottle bombs to occur.

So, does anyone know if there are some experimental charts or facts that match the finishing gravity numbers to the amount of priming sugar added to achieve consistency in the volume of C02 in bottle conditioning?

Thanks for any help you guys can give.

Trip

I have been trying to research information regarding how much priming sugar to use for bottle conditioning at different stages of final gravity. What I mean is that if you have a beer with a final gravity of 1.012 vs. another with a final gravity of 1.005, what amount of priming sugar is optimum for each to attain a consistent volume of Co2 in the bottle.

I guess the easy answer is to bottle from a keg with beer already carbonated. That may be true for some styles but when you are talking about Strong Belgians and Bavarian Wizen biers, the sediment from the bottle conditioning is key to some of their flavors.

I have read and used the standard 2/3, 3/4 cup cane sugar in 3 cups of water, boiled then chilled and added to the racked beer before bottling. However, it has been my experience that depending on how much residual fermentable sugar remains in the beer sometimes causes bottle bombs to occur.

So, does anyone know if there are some experimental charts or facts that match the finishing gravity numbers to the amount of priming sugar added to achieve consistency in the volume of C02 in bottle conditioning?

Thanks for any help you guys can give.

Trip