You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

What's the minimum mash temperature?

- Thread starter spiff2268

- Start date

Help Support Homebrew Talk - Beer, Wine, Mead, & Cider Brewing Discussion Forum:

This site may earn a commission from merchant affiliate

links, including eBay, Amazon, and others.

Stillraining

Well-Known Member

You "can" mash much lower then 146 it just takes longer. I don't get excited when my temps drop into the low 140's on light crisp beers.

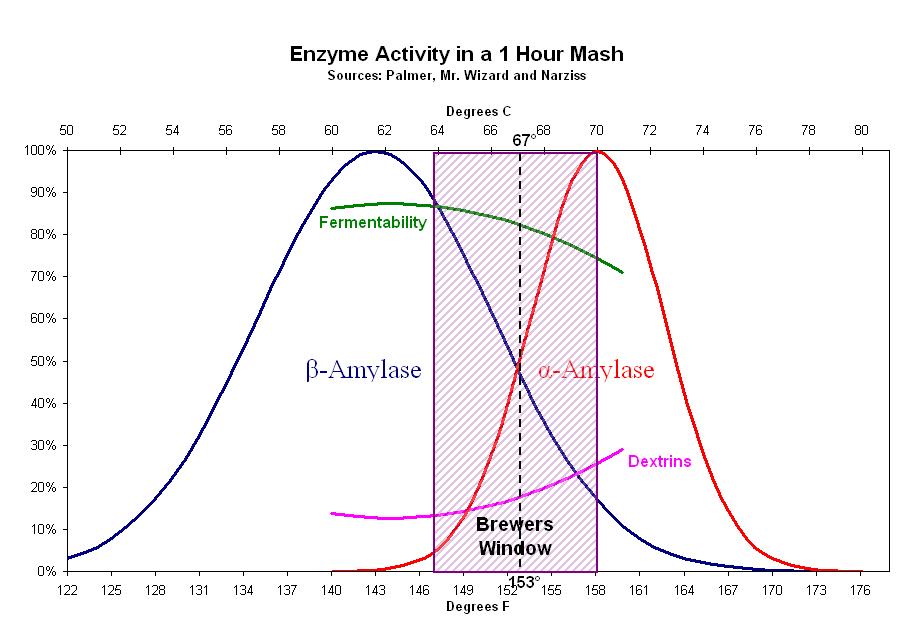

To get the starch to convert to sugars for fermenting requires the action of alpha and beta amylase. Alpha amylase breaks down the starches to long chain sugars, beta amylase breaks the long chain sugars to short chain, fermentable sugars. You need to mash in the range where both of them work. If I interpret this graph correctly, about 143F would be the minimum to get both working and the alpha amylase activity would be minimal so you would need more time for it to work.

https://missionarybrewer.files.wordpress.com/2012/02/enzyme_activity_one_hour_mash.jpg

https://missionarybrewer.files.wordpress.com/2012/02/enzyme_activity_one_hour_mash.jpg

To get the starch to convert to sugars for fermenting requires the action of alpha and beta amylase. Alpha amylase breaks down the starches to long chain sugars, beta amylase breaks the long chain sugars to short chain, fermentable sugars. You need to mash in the range where both of them work. If I interpret this graph correctly, about 143F would be the minimum to get both working and the alpha amylase activity would be minimal so you would need more time for it to work.

So ideally we would start the mash at 158 and then drop to 143 once the starch is all converted?

Why do we insulate out mash tuns/BIAB pots?

McKnuckle

Well-Known Member

You can't do that, because at the higher temperatures it's not just a matter of beta amylase being less active; it actually begins to denature (which renders it permanently inactive). This apparently takes more time than most brewers would be led to believe - it's always implied that beta "dies" instantly at 158 - but in a long mash, it would certainly happen.

You can't do that, because at the higher temperatures it's not just a matter of beta amylase being less active; it actually begins to denature (which renders it permanently inactive). This apparently takes more time than most brewers would be led to believe - it's always implied that beta "dies" instantly at 158 - but in a long mash, it would certainly happen.

This is it exactly, you have to make the two enzymes work together which is why the graph has the "brewers window" part shaded. If your grains are milled an average thickness you can work with that window to favor body or fermenability by choosing a mash temp that will get you there. Your mash temp of 150 will get you a more fermentable wort than one at 156 and a little less than one at 148 or 146.

If you mill the grains really fine, you lose some of the control over the fermentability because with larger grain particles, you need to mash longer and with higher temperature you will begin to denature the beta amylase before all the starch is converted so you get a more dextrinous wort, a wort that is less fermentable. With the finely milled grains that I use, conversion happens so quickly that neither enzyme gets denatured before all the starch is converted so my wort is more fermentable than I would expect from the temperature of the mash and I get a drier beer.

McKnuckle

Well-Known Member

Hey @RM-MN, I've read your short mash time posts many times and it has always interested me. I've wondered, though: even though the conversion of starches to sugars may occur quickly, isn't it still necessary to allow beta amylase some more time to shorten the dextrins into maltose?

Similarly, I thought beta worked fairly slowly at lower mash temps, so I would think that really short mashing would be practical only at higher temps, which limits its usefulness.

Just wondering if you've made any observations about this in your brewing...? Thanks!

Similarly, I thought beta worked fairly slowly at lower mash temps, so I would think that really short mashing would be practical only at higher temps, which limits its usefulness.

Just wondering if you've made any observations about this in your brewing...? Thanks!

Recently I've developed a new theory for what is happening in 21st century mashes, because it no longer matches up with the historical curves that continue to be thrown around ad nauseum.

My theory:

With the well-modified malts of the 21st century, the amount of TIME in the mash matters way more than the precise temperatures. Similarly, one should be able to mash at a lower temperature than historically true to achieve about the same results as history.

The reason for this I feel is pretty simple. We've got way more enzymes in our malts today than the days of old. The science of malting continues to evolve and improve just like anything else -- it's not stagnant! So when people say, "But beta and alpha work more slowly at lower temps", they're both right and wrong, because while they do work a bit slower, we're also throwing huge numbers of enzymes into the mash at the same time. So.... a mash for an hour today at 140 F might actually give the same results as a mash for an hour at 155 F from 100 years ago, based just on the huge amount of enzymes in there today vs. yesteryear. And then for the same reasons, a mash for 40 minutes today at 150 F might be the same as a mash for 75 minutes at 150 F from 100 years ago. There's no easy way of knowing truth without a time machine, but we could eventually develop good experiments comparing behavior of purposely undermodified malts with today's most well-modified malts. This is not a job for me, it's a job for commercial laboratories. We could play around but we homebrewers in the 21st century don't really have access to undermodified malts in most cases.

Temperatures and times shown above are for illustrative purposes, but I do believe there is a very real effect, and it has everything to do with advances in maltster technology in the 21st century and development of a lot more enzymes. These are facts that I think about 98% of brewers are ignorant of but 2% are beginning to catch onto.

Chew on that.

The way I see it, we have two options. Either we can explore the mash TIME thing, or the mash temperature thing in the lower reaches closer to 140 F. So far, I'm mashing almost every batch for just 40 minutes at 150 F, and have been for 10.5 years already. Are my beers more full-bodied and lower alcohol than others? Maybe by a point or two, but not really that anyone has been able to notice or point out. Could I instead be mashing at 140 or 145 F for 60 minutes and get the same results? I don't know, I just thought of this now. I might have to play around with that. On the other hand, to me time is precious, and I've been very happy shaving 20 minutes or more out of every single batch for the past 10.5 years.

My theory:

With the well-modified malts of the 21st century, the amount of TIME in the mash matters way more than the precise temperatures. Similarly, one should be able to mash at a lower temperature than historically true to achieve about the same results as history.

The reason for this I feel is pretty simple. We've got way more enzymes in our malts today than the days of old. The science of malting continues to evolve and improve just like anything else -- it's not stagnant! So when people say, "But beta and alpha work more slowly at lower temps", they're both right and wrong, because while they do work a bit slower, we're also throwing huge numbers of enzymes into the mash at the same time. So.... a mash for an hour today at 140 F might actually give the same results as a mash for an hour at 155 F from 100 years ago, based just on the huge amount of enzymes in there today vs. yesteryear. And then for the same reasons, a mash for 40 minutes today at 150 F might be the same as a mash for 75 minutes at 150 F from 100 years ago. There's no easy way of knowing truth without a time machine, but we could eventually develop good experiments comparing behavior of purposely undermodified malts with today's most well-modified malts. This is not a job for me, it's a job for commercial laboratories. We could play around but we homebrewers in the 21st century don't really have access to undermodified malts in most cases.

Temperatures and times shown above are for illustrative purposes, but I do believe there is a very real effect, and it has everything to do with advances in maltster technology in the 21st century and development of a lot more enzymes. These are facts that I think about 98% of brewers are ignorant of but 2% are beginning to catch onto.

Chew on that.

The way I see it, we have two options. Either we can explore the mash TIME thing, or the mash temperature thing in the lower reaches closer to 140 F. So far, I'm mashing almost every batch for just 40 minutes at 150 F, and have been for 10.5 years already. Are my beers more full-bodied and lower alcohol than others? Maybe by a point or two, but not really that anyone has been able to notice or point out. Could I instead be mashing at 140 or 145 F for 60 minutes and get the same results? I don't know, I just thought of this now. I might have to play around with that. On the other hand, to me time is precious, and I've been very happy shaving 20 minutes or more out of every single batch for the past 10.5 years.

@dmtaylor. Interesting theory...how do you think that would affect a step mash, or possibly a "ramp" mash? IDK if that's a real term, but describes what I mean by mashing in low (say ~140⁰ then slowly raising the mash temp to mashout at ~ 165-8⁰ over the period of 40-60 minutes? Would that not also give the Beta & Alpha-Amylase the best chance for conversion?

then slowly raising the mash temp to mashout at ~ 165-8⁰ over the period of 40-60 minutes? Would that not also give the Beta & Alpha-Amylase the best chance for conversion?

Hey @RM-MN, I've read your short mash time posts many times and it has always interested me. I've wondered, though: even though the conversion of starches to sugars may occur quickly, isn't it still necessary to allow beta amylase some more time to shorten the dextrins into maltose?

Similarly, I thought beta worked fairly slowly at lower mash temps, so I would think that really short mashing would be practical only at higher temps, which limits its usefulness.

Just wondering if you've made any observations about this in your brewing...? Thanks!

My beers seem to attenuate well, perhaps better than I would wish for at times. The one batch that I mashed for only ten minutes seemed to hit the same FG as the same recipe that mashed for 20 and 30 minutes. What it lacked that the longer mashes gave me was flavor. It seems to take longer for the flavor to be extracted from the grains, in this case the caramel malt.

@dmtaylor. Interesting theory...how do you think that would affect a step mash, or possibly a "ramp" mash? IDK if that's a real term, but describes what I mean by mashing in low (say ~140⁰then slowly raising the mash temp to mashout at ~ 165-8⁰ over the period of 40-60 minutes? Would that not also give the Beta & Alpha-Amylase the best chance for conversion?

I still think it's more a time factor. If you raise temp over 40-60 minutes, both the beta and alpha amylase are very active for most of that time, at least until the beta becomes denatured in the second half. If anything, you could expect lower attenuation and higher final gravity than a single infusion from killing off the beta, unless you maintained the temperature at 140 F for a good 15-20 minutes before ramping up.

I might be totally wrong on this. But of course I think I'm right. Your experience could still turn out differently though, as I've not played enough with steps or ramps to know for certain. It's fun to play around and learn for yourself though if you're interested. And if so, please share your experience.

drunkinThailand

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Nov 12, 2015

- Messages

- 108

- Reaction score

- 13

I just emailed Weyermann asking if their Vienna Malt needs a protein rest and this was the response I got

"you don’t need a protein rest for Weyermann® Vienna Malt. It is highly modified in proteolysis and you can mah-in at 62° C directly. We recommend a rest of 50 minutes at this temperature. Then heat the mash up to 68° C and hold there a rest of 10 minutes. Afterwards increase the temperature up to 72°C and a rest of 30 min. Then mash-up at 78° C. "

any thoughts?

"you don’t need a protein rest for Weyermann® Vienna Malt. It is highly modified in proteolysis and you can mah-in at 62° C directly. We recommend a rest of 50 minutes at this temperature. Then heat the mash up to 68° C and hold there a rest of 10 minutes. Afterwards increase the temperature up to 72°C and a rest of 30 min. Then mash-up at 78° C. "

any thoughts?

Similar threads

- Replies

- 12

- Views

- 733

- Replies

- 14

- Views

- 1K

- Replies

- 13

- Views

- 1K

- Replies

- 9

- Views

- 897