John Meerse

Member

- Joined

- Apr 7, 2019

- Messages

- 11

- Reaction score

- 2

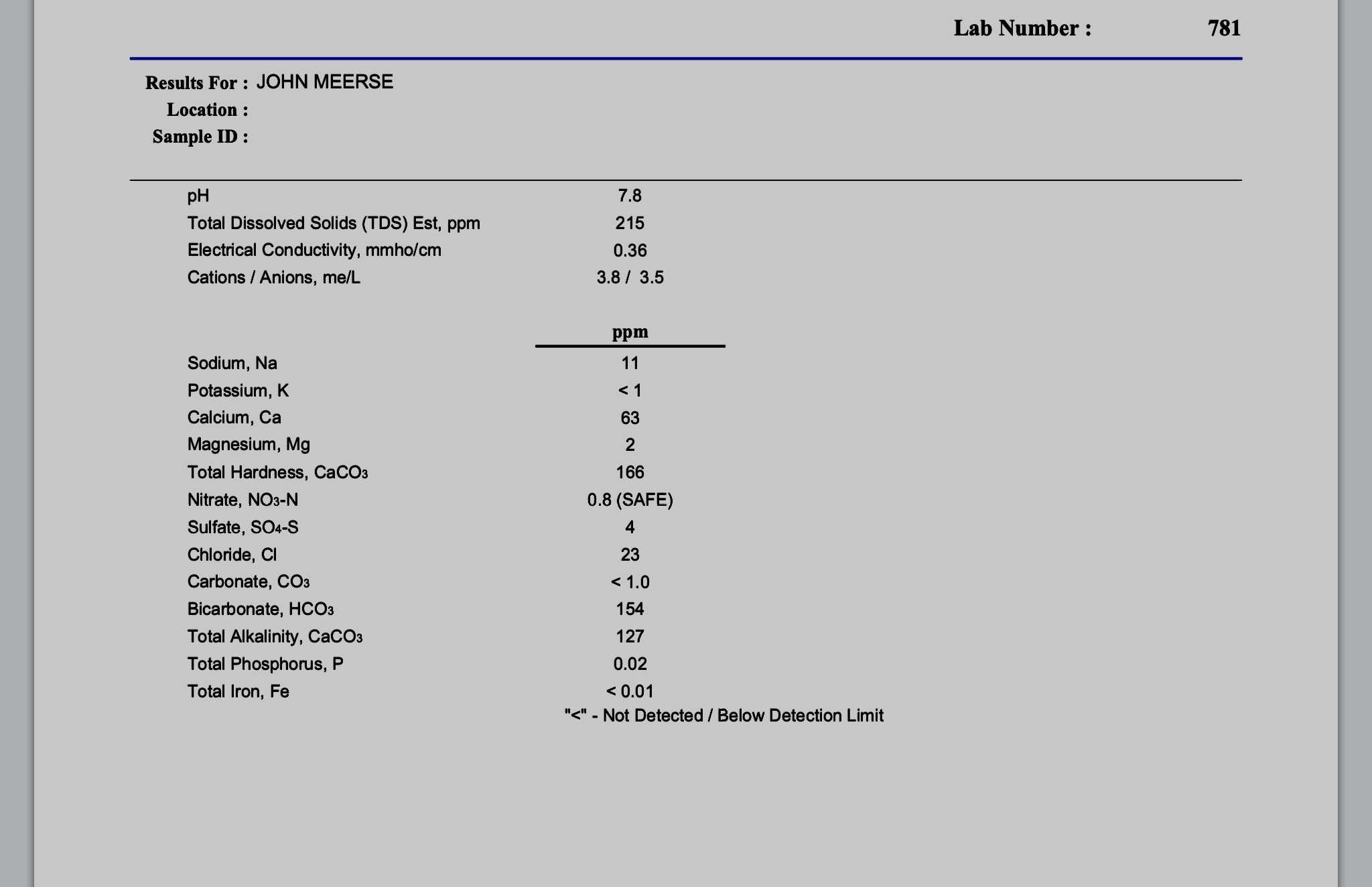

I’m planning on following A.J. deLange’s method for using slaked lime to decarbonate my water, as outlined in the Water book by Palmer and Kaminski. I’ve run through the process a couple times with small amounts of water (1 pint and 3 quarts) and feel confident I understand the process. I’m going to brew this Sunday, and so will treat my water on Saturday to allow time for precipitation to occur.

I have 2 questions: If I need 9 gallons for my mash water, how much should I treat, since I’ll be leaving some behind with the precipitate in it?

Do I need to also treat my sparge water, or is it sufficient to just treat my strike water?

I’ve been using lactic acid to neutralize the alkalinity, but I think I’m getting off flavors in the finished beer (typically about 1.25 tablespoons). I don’t have phosphoric acid, and I believe the amount of acid malt I’d need would go over the recommended limit. I don’t have access to RO water, and really don’t want to buy that much distilled water and have to recycle all those jugs.

Thanks very much!

I have 2 questions: If I need 9 gallons for my mash water, how much should I treat, since I’ll be leaving some behind with the precipitate in it?

Do I need to also treat my sparge water, or is it sufficient to just treat my strike water?

I’ve been using lactic acid to neutralize the alkalinity, but I think I’m getting off flavors in the finished beer (typically about 1.25 tablespoons). I don’t have phosphoric acid, and I believe the amount of acid malt I’d need would go over the recommended limit. I don’t have access to RO water, and really don’t want to buy that much distilled water and have to recycle all those jugs.

Thanks very much!

![Craft A Brew - Safale S-04 Dry Yeast - Fermentis - English Ale Dry Yeast - For English and American Ales and Hard Apple Ciders - Ingredients for Home Brewing - Beer Making Supplies - [1 Pack]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/41fVGNh6JfL._SL500_.jpg)